Nowhere was the cord between man and spirit more tightly bound than in the making of amatl, the sacred paper of the pre-Hispanic peoples. This paper was so important to the spiritual needs of the community, that in spite of intense repressive measures by the Spaniards, it has continued to survive and is still used to connect the unseen world with the seen. In the mid-1900s amatl underwent a rebirth which re-vitalized the relationship between the indigenous people and their ancient paper. Remarkably, even though the application is new, it is so related to its use of old that one feels an unbroken thread.

Paper was sacred to both the Mayans and the Aztecs. It was the medium on which their history and discoveries were chronicled. It kept their records of trade and tributes. It filled their libraries with documents for future generation to witness. And of no less importance, it was used in every religious ceremony as an intermediary between the people and the gods.

Records show that in 1507, when Moctezuma had to prepare for the New Fire Ceremony, a ritual of renewed life that took place every 52 years, he ordered a million sheets of amatl to be delivered to Tenochtitlan to insure that the ceremony would be successful and to avoid the wrath of the gods. The finest and whitest paper was set aside for writers and painters, for chronicling events, and for placating the gods. Once these needs were met, the remaining paper was given to the people for their personal use in rituals.

By the time Cortes arrived on the shores of Mesoamerica, there were at least forty-two papermaking centers, and they were producing almost half a million sheets of paper per year for use in tribute alone. The main papermaking centers were in the areas of what is now Veracruz, Morelos, Guerrero, Puebla, Hidalgo, and Oaxaca.

The town priests weren’t happy with the sacred reverence in which the native population held their amatl. They saw the manipulation of the paper in religious ceremonies as a form of idolatry. They prohibited the art of papermaking, and the papermakers were brought to trial. Even as late as 1889 persecution against the Otomi people of Hidalgo for papermaking was recorded. Shortly after, the traditional process of making amatl, the Nahuatl word for paper, which has come down to us as amate, was thought to have become extinct.

In 1901, an anthropologist named Frederick Starr headed an expedition into some remote regions of Mexico to record Indian customs and practices. It was during one of his excursions that he learned that the craft of papermaking had survived and was being made in the Otomi village of San Pablito, Hidalgo.

The Otomis still prepared the paper from the bark of the ficus and the bark of the mulberry tree – brown paper from the ficus and white paper from the mulberry – just as they had done in pre-Columbian times. The process had remained in tact through the centuries. And in spite of the dangers involved, these people had continued their rituals dedicated to fertility, successful crops, and curing disease.

Today three major Indian groups of the Huasteca region – the Nahua, Otomi, and Tepeha – still make the amate paper. The fact that these people retained their knowledge of this craft is nothing short of miraculous, but it was probably helped by the fact that they live in remote areas where there is nothing to exploit.

By the 1940s and 1950s, the traditional papermaking techniques were starting to die out naturally. Then in the 1960s, amate was re-discovered. A new Nahua art form was starting to develop in the Balsas River basin in Guerrero.

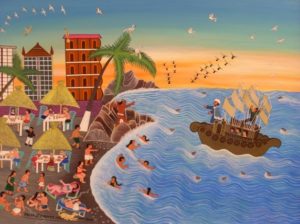

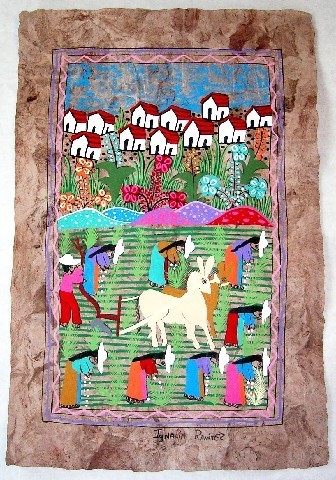

Artisans of this region, who had once only decorated their pottery, were now putting their colorful paintings on this unique paper. Ameyaltepec, a small village in the state of Guerrero, produced charming pottery painted in earth-reds which they decorated with mythical fauna and flora. In the early 1960s Max Kerlow, a folk arts dealer tired of broken pots being delivered over the mountains, introduced to the craftsmen of Ameyaltepec the idea of using amate for their painting instead of pottery. The artisan of this remote village along with those from San Agustin Oapan and Xalitla – all within walking distance from one another – started to not only work on amate but to expand their repertoire to include religious festivals and scenes of village life. They used mostly natural colors and dyes and painted with animal hair and plant fiber brushes.

Tourists in the area picked-up on the work and the popularity continued to grow through the 1970s. Although the work in the beginning was of varying quality, artists of a higher caliber eventually started to emerge who gave a more personal interpretation to their painting. Some of these artisans were now starting to sign their amate which had started to take on personal styles.

With the success of the Nahua painters, the Otomis now had an industry outside their small community. By 1974, they were producing 50,000 and 60,000 pesos worth of paper that was used for Nahua paintings. They even named a saint known as San Jonote, or Saint Bark Paper Fiber in honor of this turn around in their lives. Not only did the Otomis prosper, but there was a renewed interest in amate throughout the country.

Interest in and the reputation of the amate painters continued to grow. The work has spread beyond the borders of Guerrero and is found in tourist shops around the country. Among the better known artists, all from San Augustin Oapan, are the Camilo Ayala brothers – Marcial, Juan, and Felix. Each of the brothers is a consummate artist, and each has his own style. Their cousins, Felix Jimenez Chino, Inocencio Jimenez Chino, and Roberto Mauricio also create exceptional pieces. They’ve all gained some recognition for their artistic expression, and there are a number of patrons who appreciate and promote their work. In fact, two of Marcial Camilo Ayala’s works have been commissioned by The Smithsonian in the United States.

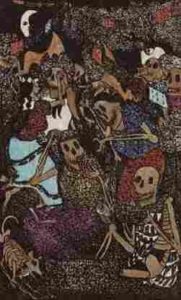

Marcial Camilo’s paintings are the most original and often depict multiple realities as in dream sequences. His brother Juan’s work reflects the animistic religion of the Nahua people with its Catholic overlay. Felix Jimenez, like his cousin, Marcial Camilo, is more of a conceptual and experimental painter.

Another well-known painter, Nicholas de Jesus, comes from Ameyeltapec and is the son of Pablo de Jesus, the very first known of the amate painters. Nicholas de Jesus has been the most successful commercially and probably the most worldly. His work is less traditional in style and he even has a studio in Chicago where he paints and does lithography.

None of the other artists have ever left Mexico, and for many, Spanish isn’t even their first language. They are simple farmers and artisans living quite removed from modern society. Aside from Nicholas de Jesus and Marcial Camilo Ayala, most amate painters eke out a meager living in the towns of their birth.

Amate painting may not have a long life. Many of the younger people see it as the work of an older generation, and these small remote communities from where the artists evolved will soon disappear. There are some art connoisseurs trying to keep the tradition alive, but it’s only a matter of time before amate painting is no longer produced. If the beauty of this folk art interests you, it’s worth looking for the work of these artists while it’s still being produced. The art form may die, but the charm and humanity of these paintings defy time.

I feel that the work done on the sacred paper of this ancient people is imbued with an energy that has no time frame, and to have an amate painting is to have a piece of eternity. For a more in depth look at amate painting, you might want to read The Amate Tradition by the anthropologist Jonathan Amith, available on Amazon.com (The entire text is presented in both Spanish and English.).

Also, you can contact Marcial Camilo Ayala by email at ayala115@hotmail.com He will know everyone in the Nahua painting community. There are many more painters than I have mentioned in the article, all living in villages close to each other and many doing high caliber work. If you are willing to make the trek to these small villages in the state of Guerrero, you will be well rewarded.

Another contact is Tyler Cowen, professor of Economics at George Mason University who can be reached at tcowen@gmu.edu He has a large and varied collection of amate paintings. Some of the beautiful examples for this article have come from his private collection and are gratefully reproduced here with his permission.

Arts of Mexico