Arts of Mexico

The coming of the Spaniards in 1519 drastically altered the political and religious life of pre-Hispanic America. Cortes, with the help of his mercenaries and priests, decimated the ruling elite and wiped out the existing theocracy, but try as they might, they could not destroy the people’s love and need for ritual.

The Spanish chronicles mention the rituals and even list the different disguises worn by the dancers which ranged from old men and hunters to an array of animals including insects, birds, and sea creatures. Dances were performed for specific gods and everyone participated – the professionally trained, the nobility, the priests, the common people, and even the emperor.

The persistence of these rituals was a problem the missionaries couldn’t ignore. They realized that if they wanted to convert the people, they had to incorporate the pre-Christian beliefs and rituals into some of the church-based ceremonies. The best way to do that was to co-ordinate pre-Christian festivals with the church related events of the Christian calendar.

Mexican masks range from hyper-realism to pure fantasy and are always in evolution, the form dictated by the needs of the local community for which they are made and the social norms of the time.

Facial characteristics, colors, and even the materials used can change from village to village for the same ritual dances performed.

The blending of the pre-Hispanic and Christian calendars and the mix of pre-Columbian deities with Christian saints provided a basis for new religious traditions. It’s in this hybrid relationship that we can identify the Mexican masks being produced and used in dance and ritual today. They are an important link between pre-Hispanic history and the Spanish conquest of Mexico, as they represent a blending of the two cultures.

The first masked dance introduced by the Spaniards was the Dance of the Moors and Christians. The Moors were driven out of Spain in 1492 and the missionaries introduced the dance to show the superiority of the Christians. The dance was adopted by the people, and today many forms of this dance still exist. Masks continue to be used, but the style changes from village to village.

The introduction of the Dance of the Moors and Christians gave rise to a further range of masked dances, one of them recounting the Spanish victory over the Indians and their eventual conversion to Christianity. These dances are called conquest dances, and Cortes and La Malinche (his Indian mistress and translator) often appear in them. It’s interesting to note that in many versions of this dance, the Indians wear lavish costumes while the Christians are played by children.

Before the conquest many dances had a cosmic significance. Today a few of the dances still reflect the cosmology of the ancient civilization. One example is a dance called Tezcatlipoca, “smoking mirror”. Tezcatlipoca was the nocturnal, invisible god and was represented by an obsidian mirror. He could bestow or withhold fortunes and his “tona” (guardian) was the jaguar or tiger. Not only is this dance still performed, but tiger masks for other dances often feature eyes with round mirrors, clearly linking them to the god, Tezcatlipoca.

Another group of masks called chilolos, the word for mask in Mixtec, also predates Christianity. These masks are used in the dance of the chilolos, which is performed in villages in the state of Oaxaca. They are always painted red and have a fixed form with curving tusk-like projections and protruding globular eyes. This character with the odd features is believed to relate to a pre-Hispanic Mixtec figure.

These masks from Zitlala resemble helmets and are made of thick layers of leather in order to withstand the heavy blows from knotted ropes that their adversaries inflict on them during the Dance of Las Tlacololeros. Often the masks are smaller than the adult head and can only be put on wet. Note the round mirrors for eyes recalling the god, Tezcatlipoca, whose “tona” is the jaguar or tiger. Tezcatlipoca can give or take away, and this dance is done to invoke rain for the next growing season

Contemporary masquerade in Mexico can be divided into three categories. The first is derived from the “auto sacramental” or liturgical drama that treats the theme of struggle and conquest. The Dance of the Moors and Christians is a good example of this type since it is an allegory for the battle between paganism and Christianity or the triumph of good over evil.

The second category incorporates pre-Hispanic and Christian elements. The Dance of the Tlocololeros, widespread in the states of Guerrero, Oaxaca, and Morelos, is indicative of this type of dance. It centers on the hunt for a tiger that’s been devastating the fields. The hunters (Tlocololeros), who in Guerrero wear sack-like costumes, wide-brimmed pointed straw hats, and wooden masks, are believed to be rain deities. They hunt the tiger which represents the dry season.

In the city of Zitlala, a ritual battle is enacted with the protagonists wearing leather helmet masks representing the tigers. It is enacted during the festival of the Holy Cross on April 30.

The third category consists of clowns and buffoons. The Dance of the Old Men, performed in the state of Michoacan and believed to be related to the Aztec Dance of the Old Hunchbacks, falls into this category. The masks represent old men who stagger around supported by walking sticks to the amusement of the audience.

Masked clowns often clear the dance area before the performance. During the performance, they can be seen taunting the audience and mimicking the movements of the dancers.

The pre-Columbian clown or buffoon has never lost its appeal for the Mexican people. In pre-Hispanic times the huezquistle or buffoon is believed to have come down to earth from the ninth heaven to join the festivities. There are mask-makers in Mexico today who still believe in his descent. In the state of Guerrero he often displays lizards on each cheek and sometimes on his nose.

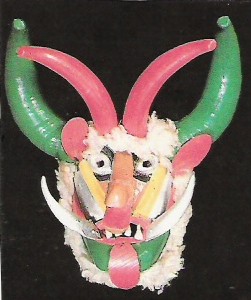

Highly imaginative devil masks are made for the annual devil mask competition in Guerrero during the 16th of September holiday. Each craftsman tries to outdo the others in his quest for the most grotesque features.

Clowns in Mexico are often seen wearing devil masks. These characters are treated as comic figures. They show up during Carnival or to honor local patron saints. The missionaries had ordered their new converts to abandon the ancient gods, calling them “demons”. The people found that by putting horns on the masks of their gods they could get round this order. Today many of the contemporary masks worn by ” el diablo” (the devil) retain some of the features of the ancient gods.

The European devil had no counterpart in the pre-Columbian world because hell didn’t exist. No one believed that bad behavior during life was punishable after death. They recognized the dual nature of people and phenomena and therefore had no concept of absolute good or absolute evil.

The devil often shows up in the company of death at festive occasions and is also a benign figure. The Aztec underworld, governed by Mictlantecuhtle, the Lord of the Dead, was just a place to go. He did not reward virtue or punish sin. Therefore, he aroused little fear in the living and could become a deity to burlesque.

Whether for serious intent or to make fun, masks are an important part of Mexican cultural and religious life, and the mask maker is a revered member of the local society. Traditionally, his skills are passed on to a son (never a daughter) or close family member, and he is respected for his great wisdom. He knows the storyline of every local dance and what features to give each different character. His product is held in such high esteem that in many villages the masks are kept in the church when not in use.

The dancers in the local communities are also highly regarded. They acquire a power over the community for that period of time in which they are performing. The pre-Hispanic belief in the transformative power of the mask has never left the people.

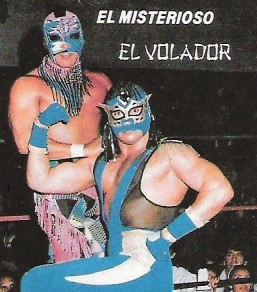

Wrestlers in modern Mexico are the new heroic figures taking the place of the old gods. Many of the posters around Mexico City show the wrestlers in full regalia in which their costumes are thinly disguised allusions to the heroic gods of their past.

Through the first half of the twentieth century, masks were used primarily in dances performed to fulfill promises made to the Virgin or to a saint in return for a miraculous intervention, or to make a communal or personal request such as bringing the rains to ensure abundant harvest or to protect from or cure illness. Now, they are just as likely to be made for the tourist market. In Guerrero, state-sponsored competitions encourage innovation in mask making, and the creativity among the mask makers is extraordinary. Some of the new styles have influenced masks used in village ceremonies, but the main trend today is towards secularization and the market place.

But make no mistake. The thirst for ritual and the power of transformation that only a mask can instill continues to live in the hearts of the Mexican people. In Mexico City there are cults around contemporary real-life masked heroes. Mexican wrestlers are usually masked, and the victor unmasks his opponent. This is very close to the Aztec ceremony of taking away the masks of the enemy to take away his power.

In recent years, Superbarrio has come on the scene. He is the masked defender of the poor who provides a rallying point against corruption and inefficient government. Is there really that big a gulf between the people’s faith and belief in Superbarrio and those more ancient men-gods that the Spaniards could never quite lay to rest?

Dear Ms. Pomade,

The wood mask that you show in your article labled “Cristian Mask” is NOT Mexican. It is from Guatemala, and is most likely an “Alvarado”.

Joel, Thank you for your valued correction. The photographs were an editorial responsibility, not Ms Pomade’s. I have now amended the caption to make it clear that the mask in question is from Guatemala. We appreciate your help in improving the content offered on MexConnect and hope you will continue to enjoy the site. Best wishes, Tony.