The art and attitudes of the two great Mexican muralists, Diego Rivera and José Clemente Orozco could not be more different. Rivera was a classicist, Orozco an expressionist. Rivera was optimistic, Orozco was a pessimist. Rivera was an indigenista who idealized the Indian segment of Mexican society and glorified pre-hispanic culture. Orozco was a hispanista who admired the Spanish conquerors as a civilizing force in a barbaric world. Rivera has been called the Mexican Revolution’s ballad singer, Orozco its interpreter and critic, Rivera its “proud historian,” Orozco its “tragic poet.”

The Russian filmmaker Sergei Eisenstein, who knew both artists when he worked in Mexico in the 1930s, saw them in terms of the Apollonian/Dionysian antithesis. Yet, he wrote, “It is ridiculous to talk of Apollo when we look at the Rabelaisian, fat-bellied figure of Diego, his flesh bursting out from overtight trousers and his greasy skin appearing tightly stretched from his face to his stomach. It is equally difficult to think of Dionysus in referring to an individual [Orozco] of Promethean proportions…, protected by enormous round glasses with lenses as thick as portholes….” Eisenstein saw Rivera as static, “…the nerve of reality is fixed as though with a nail to the wall.” Orozco’s art he called “A scream on a surface through form and through style.”

The contrast between the painter’s personalities was equally dramatic. Rivera was affable, garrulous and gregarious. Orozco was a taciturn lone wolf. Rivera had a life-embracing, sensuous and deeply curious love for people. Orozco had an intense tenderness that was often masked by corrosive irony. Rivera loved to work surrounded by people whom he regaled with a steady flow of theory, opinion and outrageous tall tales. Orozco preferred complete privacy in his studio.

These two leaders of the Mexican mural renaissance that began in 1920 are opposites who compliment each other so perfectly that to focus on the art and ideas of one illuminates the work of the other. In Mexico it is said that “if one had not existed the other might have ceased to exist.”

They admired and competed with each other. In 1925 Rivera said: “José Clemente Orozco, along with the popular engraver, José Guadalupe Posada, is the greatest artist, whose work expresses genuinely the character and the spirit of the people of the City of Mexico. …Profoundly sensual, cruel, moralistic, and rancorous as a good, semi-blond descendent of Spaniards, he has the force and mentality of a servant of the Holy Office…in all his work one feels the simultaneous presence of love, of pain and of death .” Orozco was more withholding of praise. His compliments to Rivera were usually back-handed, and in his letters, he called Rivera “potentate,” “Poor Fat Man,” the “Great Folkloric leader,” and “Diegoff Riveritch Romanoff.” He bitterly resented Rivera’s mania for publicity and the way Rivera set himself up as “the great creator of everything” with the other muralists playing the role of his disciples.

Legend has it that when in 1934 Orozco finished his fresco Catharsis in the staircase of Mexico City’s Palace of Fine Arts, he crossed the hall carrying his wet brush and handed it to Rivera who was not yet finished with his remake of the destroyed Rockefeller Center mural. “Maybe this will help you to finish,” Orozco is said to have said.

As their autobiographies show, their lives were distinct. Rivera’s was full of drama, scandal, women, glamorous people, politics, pleasure and work. Orozco’s life was full of work. As Orozco described his autobiography published in 1942: “There is nothing of special interest in it, no famous exploits or heroic deeds, no extraordinary or miraculous happenings. Only the uninterrupted and tremendous effort of a Mexican painter to learn his trade and find opportunities to practice it.”

The artists’ images of themselves in self-portraits are telling. Rivera, a great self-mythologizer, painted himself often. Unlike Orozco who refrained from inserting himself into the walls he painted, Rivera turns up in many of his frescos, for example, in his 1930 The Making of a Fresco at the San Francisco Art Institute, where he demonstrates his idea of the artist as a laborer by picturing himself on a scaffold, a worker among workers. His presentation to the viewer of his fat back side was felt to be a premeditated insult in some San Francisco circles, and when Orozco saw the picture he voiced his disapproval. In 1940 Rivera made a double appearance in his Pan American Unity mural at the City College of San Francisco, where he is seen first in blue work clothes painting, next as a small boy seated on the floor drawing, and finally as a grown man holding hands around the tree of love and life with the film star Paulette Goddard. He turns his back on his third wife, the painter Frida Kahlo, whom he had divorced in 1939 and was about to remarry. Paulette Goddard he said, stands for “American girlhood…shown in friendly contact with a Mexican man.” Asked why he had painted himself holding hands with Goddard (who is said to have been a contributing cause in his divorce) Rivera replied: “It means closer Pan-Ameri-canism.”

Rivera also entered his murals in various disguises: in the Cortez Palace in Cuernavaca he was Morelos, at the National Institute of Cardiology he appeared as an eminent cardiologist, and in his mural sequence at the Ministry of Education he was an architect. His self-presentation is often full of humor, as when he painted himself as a small boy with a frog and a snake in his pockets, and with Frida Kahlo’s motherly arm around his shoulder. Rivera’s self-portraits have an intimate, contemplative calm. Orozco’s are agitated. Orozco’s Self-Portrait from 1949 shows the painter as an intellectual, a man of self-doubt, and of passionate morality. His blazing eyes bore into the viewer. They contain all the anger and tenderness with which he observed the sufferings and foibles of the Mexican people.

Orozco and Rivera were born three years apart, Orozco in Ciudad Guzmán in 1883, and Rivera in Guanajuato in 1886. As young children, both moved with their families to Mexico City. Both studied art at the Academy of San Carlos, and both felt their real teacher was the turn-of-the-century broadside engraver Posada whom they claimed to have watched at work when they were mere schoolboys. Orozco recalled: “I would stop and spend a few enchanted moments in watching him, and sometimes I even ventured to enter the shop and snatch up a bit of the metal shavings that fell from the minium-coated metal plate as the master’s graver passed over it. This was the push that first set my imagination in motion and impelled me to cover paper with my earliest little figures; this was my awakening to the existence of the art of painting.” Similarly, Rivera said he pressed his nose so often against Posada’s workshop window that the engraver came out and befriended him. Both stories may be invented, but it is true that these artists inherited much of Posada’s humor and imaginative bite. Orozco in particular was known as a cartoonist before he became a mural painter.

Both Orozco and Rivera had a passionate love for Mexico. Their central subject was Mexican history, and their murals reveal their complex and contradictory approaches to that story. They wanted to create an art that would give the Mexican people a pride in themselves and in and their heritage. To a great extent they succeeded. Their murals changed the way Mexicans saw themselves, and they changed as well, the picture of Mexico formed in the minds of people all over the world.

During the period of reconstruction that followed the armed battles of the revolutionary decade from 1910 to 1920, Mexican culture engaged in a search for a Mexican identity. In music, literature, theater, dance and painting there was a “return to origins,” a reaffirmation of Mexico’s indigenous past. Pre-Columbian art and popular art was re-valued. Sophisticated city women began to dress in native costumes, and painters not only populated their works with Indians and native artifacts, they also imitated the folkloric style of popular art. Rivera was the leader of this folkloric trend. Orozco couldn’t stand it. In 1923 he wrote: “Personally I detest representing in my works the odious and degenerate type of common people that is generally taken as a ‘picturesque’ subject to please the tourist or profit at his expense. We are chiefly responsible for having permitted the creation and fostering of the idea that the ridiculous ‘ charro’ and the vapid ‘ china poblana’ represent so-called Mexicanism….These ideas induce me to abjure, once and for all, the painting of huaraches [sandals] and dirty cotton pants. …in all of my serious works there is not a single huarache or a single sombrero….”

The reaffirmation of Mexico’s indigenous culture in the 1920s had much to do with President Obregon’s brilliant Minister of Education José Vasconcelos, a lawyer and philosopher who had participated in the revolt against the dictatorship of Porfirio Diaz. Acting on his idea that the “The Spirit Shall Speak Through My Race,” Vasconcelos launched a crusade to educate the Mexican people and to bring the Indian into the body politic. Realizing not only that many Mexicans were illiterate and that, as he put it, “Men are more malleable when approached through their senses as happens when one contemplates beautiful forms and figures…,” he commissioned painters to work at mason’s wages decorating public walls with paintings that could teach the people.

Orozco and Rivera both wanted to create a truly Mexican art. Of Mexican artists of the 1920s, Orozco said: “we too had a character, which was quite the equal of any other. We would learn what the ancients and the foreigners could teach us, but we could do as much as they, or more. It was not pride but selfconfidence that moved us to this belief. Now for the first time the painters took stock of the country they lived in.” Rivera, recently returned from a fifteen year sojourn in Europe, was exhilarated by the beauty of his country: “It was as if I were being born anew, born in a new world.” He said he wanted his murals in the Ministry of Education “…to reproduce the pure basic images of my land. I wanted my painting to reflect the social life of Mexico as I saw it, and through my vision of the truth to show the masses the outline of the future.”

The ways in which Orozco and Rivera painted history are diametrically opposed. In his gigantic mural on the staircase of the National Palace in Mexico City Rivera envisioned the sweep of time as an immense and colorful panorama, starting with the Pre-hispanic period on the right, and moving leftward, through the conquest, the War of Independence, the revolution and finally, on the left, to the present and even the future. With his gargantuan appetite for life and his irrepressible curiosity, he wanted to include everything. As a result, his mural teems with so much detail that the viewer is at first overwhelmed. One must read his mural like a book, examining first one part and then another, until one forms a vivid picture of the story of Mexico.

By contrast, Orozco’s vision of history, for example, in his 1932 mural sequence in Dartmouth College’s Baker Library, is spare. He selects key moments which he abstracts and synthesizes. He discards incident, breaks up logical narrative sequence and retains only the essence of Mexico’s origins and evolution. In his view, there are a few important historical figures, namely the white bearded priest/god Quetzalcoatl, Cortez, Zapata and an angry Christ who returns to destroy his cross, because, as Orozco saw it, human beings made such a botch of history that Christ realized that his sacrifice had been in vain. Orozco draws a parallel between Quetzalcoatl and Christ. Unappreciated by their people, both these part human, part divine saviors left this world vowing to return.

Rivera with his increasing nostalgia for the past, painted an idyllic view of Mexico before the Spanish intervention. To Rivera the conquest was a disaster. He depicted cruel and greedy conquistadors branding and enslaving the natives, and the venal Catholic church in cahoots with the conquerors. His Cortez was a despot and a degenerate—his National Palace mural shows Cortez as a syphilitic. Orozco felt differently. The Cortez he painted in the National Preparatory School in Mexico City in 1926 is heroic and protective. As the conqueror steps on a slain Indian and joins hands with his Indian mistress Malinche, he stands for the origin of the new mestizo race. Orozco’s later Cortez at Dartmouth is an even more indomitable hero, albeit a mixed blessing of a hero, for here he is shown as an armoured man, a man of steel who led the way to the dehumanizing industrial era.

Orozco thought more highly than did Rivera of the role of the church in the colonial period. To him the Catholic priests were an improvement over the blood-hungry pre-Columbian gods and their tyrannical and superstitious priests who performed cruel human sacrifices. His Franciscan missionaries at the National Preparatory School lift the Indians out of abject misery. The image of Christian charity is less tender in his later mural sequence in the former chapel of the Hospicio Cabanas, an orphanage in Guadalajara whose nave walls he painted in 1938 and ’39. Here the Conquest is a terrifying apocalypse. Cortez is transformed into a robot, and the conquistadors’ horses become two-headed monsters or war machines. The heated imagination of this imagery becomes even more feverish in Orozco’s subsequent murals at the Supreme Court of Justice and the Hospital of Jesus in Mexico City.

Orozco’s murals universalize his subjects. Rivera’s are rich with specificity. Orozco wrote in connection with his Dartmouth frescoes: “In every painting, as in any other work of art, there is always an IDEA, never a STORY. The idea is the point of departure, the first cause of the plastic construction, and it is present all the time as energy-creating matter….The important point regarding the frescoes of Baker Library is not only the quality of the idea that initiates and organizes the whole structure, it is also the fact that it is an AMERICAN idea developed into American forms, American feeling, and as a consequence, into American style.”

Although Rivera said that it was the masses that propelled history forward, and his history of Mexico painted at the National Palace is a dialectic of good and evil and of class struggle, his vision of history is, like Orozco’s, dominated by leaders from Quetzalcoatl to Cortez to Hidalgo to Zapata to Karl Marx. Where Orozco drew a parallel between Quetzalcoatl and Christ, Rivera draws a parallel between Quetzalcoatl and Marx, who is seen at the top of the section called Mexico Today and Tomorrow. Displaying a document that says “The whole history of human society to this day is the history of class struggle,” Marx points towards peace and resolution in an industrial utopia.

For Rivera the optimist, history moves in the direction of Marxist revolution. For Orozco, on the other hand, history leads to more chaos and more war. He did, however, begin his work at Dartmouth with an image of man liberated from mechanization, and he ended his Dartmouth mural cycle with hopeful images of workers reading and building. But his heart wasn’t in it, and his real vision of the end of history is in the return of the Messiah to destroy his cross.

Orozco did not idealize the Mexican past as did Rivera. He said that “the great dramas of humanity do not need to be glorified, for they are like manifestations of natural forces such as volcanoes.” From his point of view no matter how much the world changed, the same evils—war, injustice, poverty, oppression, ignorance—prevailed. He thus believed, as he put it, “in criticism as a spiritual mission and as the expressive capacity of the spirit in art.”

Orozco had little faith that human beings joining together in groups might bring about social change. He joined no political party. “No artist has, or ever has had, political convictions of any sort,” he said. “Those who profess to have them are not artists.” Unlike Rivera, whose murals are full of hammers and sickles and who did not deny their value as Communist propaganda, Orozco insisted that his murals took no partisan positions. To him all ideologies were suspect: all of them led to demagoguery and totalitarianism. This skepticism can be seen in The Phantasms of Religion in Alliance with the Military and his Carnival of Ideologies, both painted in 1936 on the main staircase of the Government Palace in Guadalajara.

Orozco’s Carnival was prophetic in bringing together the hammer and sickle, the swastika and the fascist bundle of fasces well before the Stalin-Hitler Pact. The painting lambastes Stalin, who is seen on the upper left wearing a military cap and manipulating a puppet-clown. It also attacks Mussolini, the clown in the pulpit on the right who is shown dangling a bundle of fasces from a sickle as he delivers a political tirade. Equally grotesque is Hitler in the center, wearing a Phrygian cap and an arm band with a swastika and star. Just above Hitler and slightly to his left is the Japanese Mikado waving a pair of detached clenched fists with which he juggles a hammer and a sickle. Orozco does not spare the church, represented here by an old man holding a cross. Marx, too, is ridiculed. He is the tiny bearded figure earnestly ranting just above the fresco’s bottom edge.

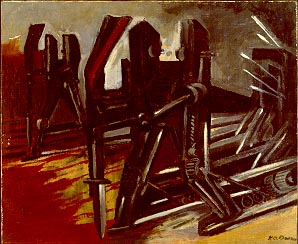

Orozco’s statements of his artistic credo are always outrageously (and misleadingly) formalist. “A painting is a poem and nothing else,” he said about his fresco Dive Bomber and Tank, which he painted in 1940 for and at New York’s Museum of Modern Art, and which expresses the terror of World War II and his distaste for industrialization.

When they lived and worked in the United States — Orozco from 1927 to 1934 and Rivera from 1930 to 1934–a period when the conservative political climate in Mexico was inhospitable to mural painting, both Rivera and Orozco were impressed by the beauty of machines. Both artists observed that machines were this country’s highest art form. But, starting with his Dartmouth mural in which the captives of the conquest are fed into the maw of fantastical machines, Orozco painted machinery as dehumanizing and destructive, whereas Rivera painted them as awesome and constructive. To Orozco, machinery meant “slavery, automatism, and the converting of a human being into a robot without a brain, heart, free will, under the control of another machine.”

From Rivera’s point of view, the Marxist revolution would take place in an industrialized country, and he was delighted with his commission in 1932 to paint murals on the subject of Detroit industry in the interior courtyard of the Detroit Institute of Arts. He painted what he called “the great saga of the machine and steel.” The steel industry, Rivera said, “has tremendous plastic beauty…it is as beautiful as the early Aztec or Mayan sculptures.” In his paean to the auto industry, he pictured the huge stamping press on the court’s south wall as a totemic idol that is based on an Aztec sculpture of Coatlicue, the goddess of earth and death, who represented the struggle of opposites in nature and in human life, a dialectic of good and evil that continues in the courtyard’s many fresco panels.

Before he began to paint these frescoes, Rivera spent months making careful studies of the Ford Rouge plant. While his depiction of what he saw is as imaginatively freewheeling as the vision that produced Orozco’s machines at Dartmouth, painted in the same year, he typically insisted on accuracy in every detail, and he was proud when the Ford workers told him he had got it right.

His Ford workers may be efficient cogs, but they labor in harmony with machinery and, unlike the victims of Orozco’s machines, they are not anonymous; indeed, many are based on portraits done from life. Perhaps because he did not want to offend his patron Edsel Ford, in his Detroit frescoes Rivera avoided any hint of the difficult work conditions at the Ford plant or the sufferings of the unemployed during these Depression years. He painted instead a timeless and ideal view of industry, one that expressed his hope that industrialization would bring a new era for humanity, a society in which the worker would control the machine and gain the power to bring peace to the world. The following year at Rockefeller Center he painted this utopian vision. Man at the Crossroads portrays a heroic worker who, like a pilot, has his hands on the levers and buttons that control progress. In this mural Rivera did acknowledge the Depression by depicting breadlines and policemen repressing political demonstrators, and this time he did offend his Capitalist patron; his addition of the portrait of Lenin prompted the Rockefellers to banish him from his scaffold. The painting remained unfinished, and was later destroyed.

Orozco’s view of New York during hard times was more pitiful and less political. He painted bleak gatherings of jobless men and he painted toppling skyscrapers that reveal a world in cataclysm. In his autobiography he wrote: “The Crash. Panic. Suspended credit. A rise in the cost of living. Millions suddenly laid off…Red faced, hard, desperate angry men, with opaque eyes and clenched fists. By night in the protection of shadows, whole crowds begged in the streets for a nickel for coffee and there was no doubt, not the slightest that they needed it. This was the Crash. Disaster.”

Orozco’s profound sympathy for human suffering was not galvanized into political activism as was Rivera’s. He insisted on the primacy of form above content once again when he said: “I paint prostitutes, the people, or the archbishop because they give me materia prima for my artistic realizations, in the same way I could paint Hitler or Stalin, without being pro-Hitler or a Stalinist. What basically interests me is art and everything that can provide me with a way to realize an art work. Thus I could just as well paint in Berlin as in Moscow.”

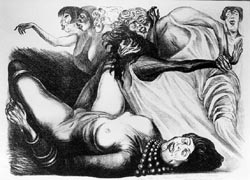

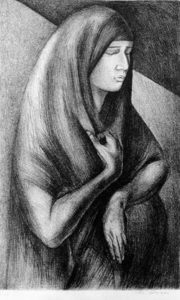

Appalled at the world’s corruption, he painted women as whores and victims. They are whores, for example in his 1934 mural Catharsis. And they are long suffering in his Women of the Workers of 1926. These female figures are a far cry from the highly sensual allegorical nudes Rivera painted at the National Agricultural School at Chapingo in 1926 and 1927. His Virgin Earth and his Liberated Earth, both of which represent his increasingly pregnant wife Lupe Marín, reveal Rivera’s huge admiration of and appetite for women.

Both Orozco and Rivera saw the creative process as something organic. Orozco said that art should “spring forth” as if it were “born of the impulse of natural forces and in accordance with their laws.” Rivera said: “I am not merely an ‘artist’ but a man performing his biological function of producing paintings, just as a tree produces flowers and fruit, nor mourns the loss each year, knowing that next season it shall blossom and bear fruit again.”

For both, making good art came before making a good world. The difference is that Orozco was open and adamant about art’s primacy. In his artistic credo written in 1923 he said: “The real work of art like a cloud or a tree, has absolutely nothing to do with morality or immorality, with good or evil, with wisdom or ignorance, or with virtue or vice…. A painting should not be a commentary but the fact itself; not a reflection but light itself; not an interpretation but the thing to be interpreted…. Everything that is not purely and exclusively the plastic, geometric language, subjected to the inescapable laws of mechanics, expressible by an equation, is a subterfuge to conceal impotence; it is literature, politics, philosophy, whatever you will, but it is not painting.”

Not surprisingly, the Communist Party had little use for Orozco. They considered him to be a bourgeois skeptic. When David Alfaro Siqueiros, the third member of the mural triumvirate, saw Orozco’s designs for Guadalajara’s Government Palace mural, he told his older colleague, “Orozco, I think you are a great painter, but you are a lousy philosopher.” Another time, the staunchly Communistic Siqueiros said: “Orozco, faithful to his traditional hermeticism and misanthropy, succumbed to apolitical passivity at the same time that he drowned in the empty symbolism of pseudo-revolutionary art.”

Siqueiros did not have a favorable opinion of Rivera’s politics either. Rivera had been active in the Mexican Communist Party from 1922 when he joined, to 1929 when he was expelled, apparently because of his stand on trade union issues and possibly also because of his admiration for Trotsky. (He was reinstated in 1954, three years before his death.) The problem with Rivera was not passivity, as with Orozco, but over-activity. Rivera was politically anarchic. As one Mexican friend mildly put it, his politics were “susceptible to circumstantial variation.” Siqueiros called Rivera a snob, an opportunist, a “mental tourist, a “dilettante in revolutionary art,” and an “aesthete of imperialism.” According to Siqueiros, all Rivera cared about was securing mural commissions. Indeed, Rivera’s muralist colleagues greatly resented his success at hogging all the best public walls. Rivera’s acceptance of commissions from Mexico’s conservative government under President Calles and from North American Capitalists such as Rockefeller and Ford, meant, in Siqueiros’s opinion, that he had sold his soul to the devil.

Although Rivera was ousted from the Party, he continued to play a political role in Mexico and to express his Communist faith in his murals. “Art,” he said, “is one of the most efficient subversive agents.” He explained away his working for Capitalists by saying that he was following Lenin’s advice to work from within the enemy camp.

Rivera’s artistic credo is the opposite of Orozco’s. Rivera said: “To be an artist one must first be a man vitally concerned with all problems of social struggle, unflinching in portraying them without concealment or evasion, never shirking the truth as he understands it, never withdrawing from life. As a painter his problems are those of his craft, he is a workman and an artisan. As an artist he must be a dreamer; he must interpret the unexpressed hopes, fears and desires of his people and of his time, he must be the conscience of his culture. His work must contain the whole substance of morality not in content but rather by the sheer force of its aesthetic facts.”

Rivera’s first mural painted in the National Preparatory School in 1922 did not express the hopes and fears of his people. Entitled Creation, it is a classicizing, art-deco-style allegory of the arts and sciences inspired by Vasconcelos’s mixture of Christian and Greek philosophy. Symbolic female figures are arranged as emanations of the male and female spirit seen below in the form of a light-skinned Adam and a dark-skinned Eve, a reference to the origins of the American race. Rivera called this mural “nothing but a big retablo,” as if it were influenced by Mexican popular art. But at this stage, his visual sources were purely European. Just before leaving Europe he had gone to Italy to study the murals of the Italian Renaissance. His rich and earthy Parisian cubism of 1913 to 1917 also informs Creation’s structure, and in his future murals, cubism would help Rivera to compose numerous details into a single structure that would not poke holes into the plane of the wall.

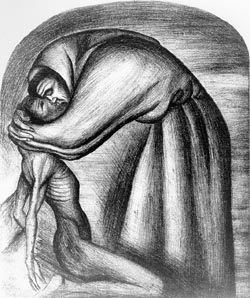

Orozco’s first mural entitled Maternity and painted in 1923 in the courtyard of the same school where Rivera painted Creation, did not focus on Mexico any more than did Rivera’s first mural. Orozco’s blond mother figure is a nude Madonna surrounded by Botticelli-like angels. Orozco compared Rivera’s Creation unfavorably with a peanut, and he called his colleague’s experiments with the golden section and cubism, “pseudoscience.” Rivera returned the insult. He said Orozco’s Maternity was “totally foreign to the exalted spirit of the painter, and of a style that caters to the herd of bucking jackasses that cannot reach with their hooves the level at which the painters’ scaffolds are set.”

In their subsequent frescoes, Orozco’s Peace, 1926, for example, or Rivera’s Rural School, 1923, both muralists found their own pictorial language. Inspired largely by Giotto, both painted simple, monumental figures that stood for all Mexican people, a type that, when borrowed by lesser artists, became stereotypical. Orozco used this rounded scheme mainly to depict rebozo-clad women, faceless soldiers and anonymous peons. When he painted the nude male torsos in The Trench, 1926, heroic, muscular chests and shoulders reveal his knowledge of classical anatomy. Some of his last frescoes at the Preparatory School, works like the Franciscan missionary or Youth, show Orozco was moving toward a leaner figure type. Then in his 1930 Pomona College mural Prometheus, he began to abandon his classical and linear mode in favor of a painterly expressionism that eventually led to the invention of figures like the beggars in Misery or The People and its False Leaders, both painted at the University of Guadalajara in 1936. Here the starving masses are freely brushed hieroglyphs of skin and bone.

In the years of reconstruction in the 1920s the Mexican muralists’ chief subject was the revolution. Mexicans, it was thought, should know their struggles and their triumphs so that they could feel themselves to be an integral part of the nation that was just being born. Rivera painted the revolution’s hopes. Orozco painted its failures. Rivera could reinvent the revolution as a beautiful epic because he was in Europe while the bloody battles were being waged. Having witnessed the revolution first hand, Orozco was unable to idealize.

In 1915 Orozco had gone to Orizaba in Veracruz where he was attached as an illustrator to Carranza’s revolutionary army. For the pro-Carranza newspaper La Vanguardia, he lampooned the armies opposed to Carranza. Non-partisan even in his youth, he also caricatured ‘the Carrancista army’s drunk and lecherous soldiers. The destruction he saw during the revolution horrified Orozco. In his typically anti-dramatic manner he wrote in his autobiography: “I played no part in the revolution, I came to no harm, and I ran no danger at all. To me the Revolution was the gayest and most diverting of carnivals…” Rivera was the opposite. He liked to pretend that he had fought alongside Zapata (and even alongside of Lenin). But the truth is that during the second decade of this century Rivera was safely tucked away in Montparnasse.

Ever contradictory, Orozco goes on in the next chapter of his autobiography, to describe the Revolution in the most poignant terms: “The world was torn apart around us. Troop convoys passed on their way to slaughter. …Trains back from the battlefield unloaded their cargoes in the station in Orizaba: the wounded; the tired; exhausted, mutilated soldiers, sweating and tatterdemalion. In the world of politics it was the same, war without quarter, struggle for power and wealth. Factions and subfactions were past counting, the thirst for vengeance insatiable…Farce, drama, barbarity. Buffoons and dwarfs trailing along after the gentlemen of noose and dagger, in conference with smiling procuresses. Insolent leaders, inflamed with alcohol, taking whatever they wanted at pistol point….A parade of stretchers with the wounded in bloody rags, and all at once the savage pealing of bells and a thunder of rifle fire… the cries of the crowd. Viva Obregon! Death to Villa! Viva Carranza! ‘ La Cucaracha’ accompanied by firing.” (La Cucaracha is the ribald revolutionary song about a drunk cockroach that can no longer walk. Orozco’s cartoon of this title shows his scorn.)

From Orozco’s point of view the revolution stopped half-way, betrayed by its supporters. His feeling of futility, anger and sorrow pervades his Preparatory School murals. In 1924 he lashed out at the corruption of contemporary Mexican life with a series of cartoon-like frescoes that include The Reactionary Forces, Political Junkheap, The Last Judgment, Law and Justice and The Rich Banquet while the Workers Quarrel.

Rivera’s Education Ministry murals, painted between 1923 and 1928, reveal a more sanguine view of post-revolutionary Mexican society. But Rivera could poke fun too, as in his Wall Street Banquet, in which John D. Rockefeller and Henry Ford dine on tickertape, or his Night of the Rich, where a blue-eyed gringo clutches a moneybag. As a good dialectician, Rivera naturally contrasted these views of privilege with views of the people. In Our Bread and Night of the Poor, his poor people look peaceful and worthy as if they were in a church (a Marxist church), whereas Orozco’s fighting workers looked as evil as his banqueting capitalists.

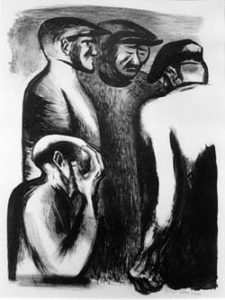

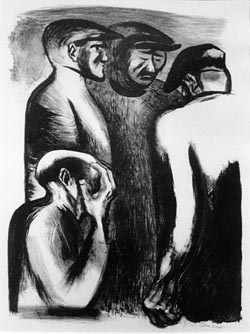

Orozco’s murals offended conservative sensibilities, and he was fired from the job until 1926, when he returned to finish his Preparatory School murals. His frescoes of 1926 are no longer cartoon-like. Now simplified, monumental figures contain all of the artist’s tenderness and compassion. His pessimism has become more tragic than angry. Revolutionary Trinity presents the urban worker, the soldier and the peasant joined together not in triumph as the trio is always shown in Rivera’s Education Ministry murals, but in despair. The peasant wrings his hands in anguish. The soldier, all brute energy and muscle, seems to have lost his foothold on the earth. He is blinded by a red flag transformed into a liberty cap. The worker, who looks with a combination of horror and dismay at the gun-wielding soldier, has lost his hands in war. He seems a particularly conflicted and tortured figure; perhaps Orozco had a special sympathy for him because Orozco himself had lost his left hand in a childhood accident with gun powder.

By contrast, Rivera’s revolutionary duo seen in The Embrace of the worker and the campesino on the first floor of the Education Ministry, is an idealized image. The farmer even has a halo formed by his tipped back sombrero, and the holiness of this revolutionary embrace is reinforced by its association with the embrace of Joachim and Anna in Giotto’s Arena Chapel in Padua. The alliance will, Rivera seems to say, bring about the well-being seen for example in the fresco just to the right which shows Indian women sitting together in the Mexican landscape.

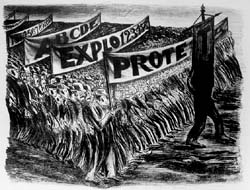

As we have seen, Rivera wanted his Ministry of Education murals to “show the masses the outline of the future.” He painted Mexicans at work in the Court of Labour and at play in the Court of Festivals. In the former, his scenes of miners entering and leaving the mine suggest that work is enabling, but they have a mood of solemnity and oppression that is augmented by the association of the image with Christ’s Road to Calvary and Crucifixion. In the court of Fiestas, Rivera combined a peasant meeting with the redistribution of the land. Upstairs in one of the Ballads of the Revolution he depicted revolutionaries agitating for political change.

By comparison with Rivera’s optimistic view of social progress, we have Orozco’s burdened workers in his Return to Work or his soldaderas (camp followers) who move across the barren Mexican land as if they were propelled, not by their own wills, but by fate. Orozco’s long-suffering women have lost their husbands, their sons and their homes in the revolution. In his contemporaneous series of lithographs entitled Mexico in Revolution, women stand or wander amidst the rubble of war without hope of finding the means to reconstruct their lives.

Orozco’s gravedigger of 1926 looks as if he were dreaming of his own death. When Rivera painted the Liberation of the Peon or The Burial of the Revolutionary, c. 1923 -1926, the scene is a solemn gathering of like-minded people and we know that this death was not wasted, but was rather a step along the revolutionary road.

Perhaps Orozco’s most poignant fresco in the Preparatory School sequence is The Trench in which three fallen or exhausted soldiers form a secular crucifixion with the gun between them becoming the top of a cross. Unlike Rivera, whose classicizing compositions stress horizontals and verticals, Orozco uses a diagonal thrust to bring the pain of his subject home. The soldiers’ heroic bodies make their defeat all the more tragic. Rivera’s Barricade looks like a jolly party by comparison.

When he painted crowd scenes, Rivera’s people come together with solidarity and purpose. The outcome of their gathering is likely to be progress, for Rivera had faith in the masses. Or the outcome might be fun, for Rivera enjoyed popular festivals, as can be seen in The Day of the Dead in the City where a sombrero-clad Rivera appears with his wife Lupe Marín just below the skeleton on the right. “Mexican muralism,” he said, “for the first time in the history of monumental painting ceased to use gods, kings, chiefs of state, heroic generals, etc., as central heroes….For the first time in the history of art, Mexican mural painting made the masses the hero of monumental art…[and] an attempt was made to portray the trajectory of the people through time in one homogenous and dialectic composition.”

When, on the other hand, Orozco painted a crowd like that in his Hidalgo in Guadalajara’s Government Palace, brutal energies are released. His groups are always squeezed together in a seething mass. Orozco’s image of The Masses in his 1935 lithograph and in his similar 1940 fresco at the Gabino Ortiz Library in Jiquilpan consists of a cluster of stone-throwing, flag-waving idiots who have no eyes to see and whose heads are huge, toothy, yelling mouths.

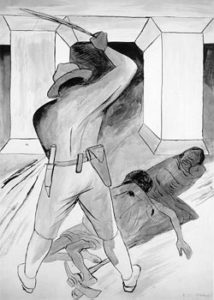

In his crowd scenes, battling bodies run each other through with knives. Indeed, Orozco seems to have had an appetite for violence even while it appalled him. The dramatic cruelty of his bodies, faces, Oman eyes stabbed with daggers or pierced with arrows makes Rivera’s battle scenes look gentle. In Rivera’s images of conquest, for example at the National Palace and at the Palace of Cortez in Cuernavaca, violence is frozen in a timeless moment whose lyrical grace recalls Uccello’s Battle of San Romano. For Rivera, violence is picturesque; for Orozco, it is enraging. As a result, Orozco’s murals wound and incite to anger; Rivera’s delight and try to set the viewer on the politically correct path.

Orozco, like Rivera believed he was painting murals for the people. As usual he was contradictory. In 1923, the very year that he and Rivera were founding members of the revolutionary painters Syndicate which published a manifesto in favor of a mural art that would be of “ideological value to the people,” Orozco came out with this query: “Painting for the People? But the People do their own painting: they don’t need anyone to do it for them.” In a different mood he wrote: “The mural is the highest, most rational, purest, and most powerful form of painting….It is also the most disinterested form since it can neither be turned into a source of private profit nor hidden away for the enjoyment of a privileged few. It is for the people. For EVERYBODY.”

Mexican murals may have been for everybody, but often nobody could understand them. The ambiguities and contradictions in Orozco’s frescoes bewildered many people, and Rivera’s murals are frequently so complex and so erudite that even an educated viewer needs a guidebook to discern their meaning.

Yet, even Rivera’s most elaborate and fantastical images like those he painted in the Lerma waterworks in 1951, are always rooted in specific, earthy (or in this case watery) details. For Rivera was an empiricist who kept his feet on the ground. (Here his feet are actually below the ground, in water.) In this hymn to water as a source of life and evolution he lets his imagination run rampant, but it never leaves the wonderful dross of palpable reality behinds. His hymn to the earth at Chapingo is similarly earthy. Here a woman (actually Rivera’s current mistress, the photographer Tina Modotti) may turn into a tree, but she does not sprout branches or reach upward like Daphne. Rather she grows a trunk and remains rooted in the earth. Even Rivera’s flames painted on the ceiling vaults look like earthbound lilies or cacti, and the petal-like licks of fire that surround the window in Zapata and Montaño Beneath the Earth blaze downward toward the cornfield that is fertilized by the two revolutionaries’ deaths.

Orozco had a more transcendent ideal. His Man of Fire in the cupola of the Hospicio Cabañas, is the opposite of Rivera’s vision of life-generating water. Orozco’s urge was to leave the dross of reality behind and to reach upwards towards enlightenment. In Man of Fire all of human life is condensed into one male figure ascending into a realm of pure flame.

With this image, Orozco fulfilled his mission to paint murals in which “the only theme is Humanity and the only tendency is Emotion to the maximum.” His mood is apocalyptic. Rising above the figures that represent earth, air and water and that ring the base of the cupola, the blazing man must stand for the one thing for which Orozco had undying respect—the creative mind. His hope for the future resided in individual spiritual liberation. “If the creative impulse were muted,” he said, “the world would then be stayed in its march.”

For all his disillusionment with the world, Orozco never lost his belief in the gifted individual’s capacity for freedom. No doubt Man of Fire is a kind of self-portrait—an artist moving upward, immolating himself in the artistic act, inspiration consuming itself as it burns. In the end, Orozco believed, beauty could be redemptive. “All aesthetics, of whatever kind, are a movement forward and not backward,” he said. “An art work is never negative. By the very fact of being an art work, it is constructive.”

Unpublished lecture delivered November 16, 1990, Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York

![]()

©1996, Mary-Anne Martin/Fine Art

Published or Updated on: January 1, 2006