Brown, arid hillsides barely visible in a distant haze. Isolated green cacti with contorted, knotted arms, coarse, spiny fingers and bright red, seemingly nailpolished fruits set against an endless tanned landscape.

This may not seem like an area likely to guard tourist treasures, but beneath the surface lie hidden surprises. For hundreds of years, chunks of rock taken, quite literally, from under your feet, have attracted people from far distant lands. Once they’ve hacked them out of the earth, they sit for hours in the searing sun, chiselling them apart. To ease their inevitably aching muscles, they then bask in magical pools of warm water, convinced that here, at last, are the long-lost fountains of youth. Where once this bathing caused Christian hackles (and later shrines) to rise, luxury spa-hotels now embody all that is best in courtesy and comfort.

This idyllic area may sound well off-the-beaten-track but is actually easily accessible – between San Miguel de Allende and Dolores Hidalgo in the state of Guanajuato. Dolores Hidalgo, now a compulsory shopping stop for anyone seeking fine Talavera ceramics, was where Hidalgo raised his rallying-call in 1810. Our starting point for exploring the area is six kilometers east of Dolores Hidalgo, exactly where highway 110 crosses the Ojuelos de Jalisco – San Miguel de Allende road, highway 51.

In ancient times, the hammering of rocks echoed across the town of Pozos some 45 kilometers to the east via San Luis de la Paz. Jesuits seeking mineral riches to finance their spiritual campaigns began mining here in 1595 but the mines proved unprofitable. The workings were abandoned until near the end of the nineteenth century when a new influx of miners arrived, eager to try their luck. In 1895, with delusions of golden grandeur awaiting their picks and shovels, they temporarily rechristened their small, dusty home Ciudad Porfirio Diaz, in honour of Mexico’s then president. Today, Pozos, originally founded as a military garrison in 1576, is a ghost town.

And what is there to see in Pozos today? Perhaps not as much as in some other altiplano ghost towns like Real de Catorce, but exploring Pozos’ crumbling stone walls and roofless houses, harbouring more insects and reptiles than people, recalls the earlier, more prosperous times when Pozos was a municipality. Lovers of the mystical quality of ruins will find enchantment in the mystery, abandonment, and inevitable sense of decay which pervades the atmosphere. In the same building as the town’s small museum, an enterprising group of young artisan-musicians handcraft modern-day replicas of ancient musical instruments.

And what is there to see in Pozos today? Perhaps not as much as in some other altiplano ghost towns like Real de Catorce, but exploring Pozos’ crumbling stone walls and roofless houses, harbouring more insects and reptiles than people, recalls the earlier, more prosperous times when Pozos was a municipality. Lovers of the mystical quality of ruins will find enchantment in the mystery, abandonment, and inevitable sense of decay which pervades the atmosphere. In the same building as the town’s small museum, an enterprising group of young artisan-musicians handcraft modern-day replicas of ancient musical instruments.

A few minutes from the junction of highways 110 and 51, along the Independence route towards San Miguel de Allende, is Adjuntas del Río, a good place to buy handcrafted mesquite furniture. The “Río” in question is the Río La Laja (“Stone Slab River”).

Fifteen minutes drive further south is a road to the west signed “Atotonilco”. If Pozos is a one-horse-town, this Atotonilco (there are several other towns of this name in Mexico) is definitely a one-shrine-town. But what a shrine! The labyrinthine Convent of Jesus Nazareno was begun in 1740, and mostly completed by 1748. Its interior has copious black, red and grey murals decorating it which were painted by an indigenous artist, Miguel Antonio Martinez de Pocasangre. The paintings, illustrating biblical scenes and accompanying verses written by Father Luis Felipe Neri de Alfaro, the shrine’s founder, helped educate the Indians in the beliefs of the church. In 1802, Independence hero Ignacio Allende took wedding vows at the altar. From this church, in 1810, Hidalgo removed an embroidered tapestry of the Virgin of Guadalupe to use as his army’s banner.

And why did Father Alfaro build such a magnificent church here? Local lore, supported by historians, is that weary miners and farmworkers, tired after long hours, would relax here in the natural, warm-water springs. According to the good Father’s journal, he sensed sin emanating from the ground in and around San Miguel – he singled out the myriad hot springs and the time-honoured tradition of bathing in them, a pretext, said the Father, for people “getting together”. So, to combat the evil, he ordered the erection of the Atotonilco (which means “place of hot water”) shrine.

Pardoned, presumably for at least one of their sins, but unrepentingly recidivist nonetheless, the local populace were tempted into embracing Satan anew by making orange-wine. They say the taste takes away the dust of the streets…

Back on the highway, headed south and hopefully not too light-headed, don’t miss the turnoff to the Rancho Hotel Sakkarah. There’s nothing Nahuatl about this name, but better that you ask Sr. César Sanchez, the hotel’s friendly manager, for the definitive version of its origin.

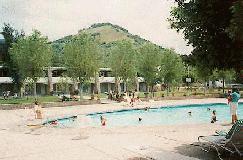

The Rancho Hotel Sakkarah is another surprising find in what otherwise looks to be a barren, non-arable, non-irrigated wilderness. Its six double rooms and two suites (all with T.V.) are more than comfortable. Complemented by a restaurant, pool and jacuzzi and set in a mere 53 hectares of ranchland, this is a modern, whitewashed, Moroccan-style “folly”, albeit it in the middle of nowhere!

The Rancho Hotel Sakkarah is another surprising find in what otherwise looks to be a barren, non-arable, non-irrigated wilderness. Its six double rooms and two suites (all with T.V.) are more than comfortable. Complemented by a restaurant, pool and jacuzzi and set in a mere 53 hectares of ranchland, this is a modern, whitewashed, Moroccan-style “folly”, albeit it in the middle of nowhere!

And why did anyone want to build a ranch-hotel in this out-of-the-way location, some 1700 meters (5700 feet) above sea level? Because, millions of years ago, in Mesozoic times, this was the shoreline of the country, and the preferred habitat of now extinct sea creatures called ammonites. Their fossilized remains, found in abundance on the hotel’s estate, gave rise to an international Earthwatch project to investigate them. The Earthwatch workers needed somewhere to stay… and the rest is recent history. Fortunately for non-fossilized tourists, the students, modern rock-splitters so to speak, mainly come here during their summer vacations!

For a change of scene, muscle-relaxing baths, and to extract cholla cacti spines from their skin, many of the students undoubtedly repair to one of the thermal spas back on the main highway. The students probably prefer the traditional Mexican atmosphere and fun of the relatively inexpensive Parador Del Cortijo with its 38 degree waters. Their older, and wearier, professors, on the other hand, perhaps opt to bathe in the even warmer waters of the Hacienda Taboada.

Eight kilometers north of San Miguel, this delightful hotel has, to quote its brochure, “Magic water” – “45 degrees Celsius, crystalline, odorless and potable, rich in bicarbonate of soda, astringent and toning for the skin and relaxing for the nervous system.” Soaking in water like that, whether privately in a tub in your room or publicly in one of the hotel’s swimming pools, before walking through the immaculately kept gardens with emerald green grass and exotic flowers, to enjoy an international buffet… what more could even the most discerning visitor want?

The Hacienda Taboada offers service second to none, even including, in every room, a well-written booklet detailing hotel services and local sites of tourist interest. According to the booklet, the ranches either side of the highway between Taboada and Atotonilco are famed for preparing strange-coloured tortillas – pastel colours such as lavender, deep colours such as red and orange, and even, believe it or not, large multicoloured tortillas like giant medallions or coins. Personally, I decided that the guaranteed quality of the hotel food overcame my consuming curiosity to sample maize-flour centenarios.

After all this, “Oh! Sooo exhausting!??” exploration of the local spas in these far-from-inhospitable wilds of the state of Guanajuato, discovering some of its less-publicized treasures, it’s on to San Miguel de Allende for a well-deserved rest…