Several small towns in northern Mexico offer a welcome respite and interesting overnight stop for tourists bored by the long and monotonous stretches of desert driving on their way south. One such destination is Sombrerete, mid-way between the cities of Durango and Zacatecas.

The Town

According to some, there was so much silver in this area that early explorers in the 1550’s discovered it by accident, finding molten silver congealing in the dying embers of their campfire! Probably founded in 1555, Sombrerete was named for a nearby sombrero-shaped hill, whose shape resembled the typical three-cornered Spanish hat worn in the sixteenth century.

In 1561 local mines produced copious quantities of silver ore, but an alliance of local Indian tribes attacked the Spanish settlement. The Spanish residents, admittedly few in number, were reduced to eating cactus fruit or tunas, the fruit of the prickly pear. This Indian “rebellion” was quickly squashed by Pedro de Ahumada Sámano, who subsequently installed several strategically-placed military garrisons.

Silver transformed into buildings

Sombrerete recovered and went on to become a wealthy mining town, reaching its zenith in the last quarter of the seventeenth century when for several years, it seriously rivalled the supremacy of Zacatecas. In 1681 a regional tax office was opened in the town to collect the tax on silver as close to the source as possible. Sombrerete’s opulence was transformed into an abundance of ancient, solidly-constructed stone buildings. Afterwards, as ore became harder to find and harder to mine, the deepening shafts becoming difficult to drain, the town fell into a slow and steady decline, though its buildings survived to tell their tales.

Sombrerete may be only a small town but it conceals so many historic buildings that it is hard to know where to begin. A succession of arcaded blocks defines the town’s centre. Each step carries you back another fifty years…. From one baroque church to another…. A few minutes on foot takes you from the attractive eighteenth century church of San Francisco to the Santuario de la Soledad, built in 1740, then to the church of San Juan Bautista, dating from the same century. A few steps further is the late seventeenth century Templo de Santo Domingo, another architectural jewel. Almost in the centre of town is the sixteenth century (1567) Franciscan convent of San Mateo, with its baroque doorway and two-storey cloisters. Adjoining it is an equally venerable architectural masterpiece with an unusual elliptical plan, virtually unique in Mexico, the plateresque Chapel of the Third Order.

Sierra de Los Organos – Valley of the Giants

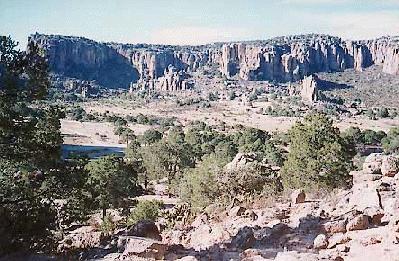

Sierra de los Organos, or Valley of the Giants, is about 7 kilometres north of the highway (though sign posted as further) close to the nondescript small village of San Francisco de los Organos. The junction is about 12 kilometres west of Sombrerete along the main Durango road. The dirt track to the Sierra de los Organos is passable all-year in regular vehicles, though care should be exercised when crossing the small dry gulleys, which are enlarged following every rainy season. Given the multitude of tracks, when in doubt at any bifurcation, choose either the more travelled track or that which is nearer the rocks. The track passes a small lake, teeming with migratory birds during the winter.

After fifteen minutes or so, you enter a broad valley, several kilometres wide, protected from the excesses of the elements by a semi-circle of rocky crags. Columnar basalt pillars (resembling organ pipes) compete with precariously-perched blocks. All these rock formations are in pine-madrone-cactus forest – a vegetation designation not found in any world classification but particularly appropriate to this area! Keep your eyes open when scrambling about on the rocks since many small prickly pear and biznaga cacti, armed with penetrating spines, lie in wait for feet inadequately protected by thin-soled tennis shoes.

Despite having no services, this lovely area, officially designated a National Park, is good camping country. Views vary considerably from one ridge to the next and narrow, dry, sandy valleys testify to the erosive action of streams which, after the rains, splash across the stepped landscape, forming waterfalls and rapids. Children playing “cowboys and indians” here are following in the illustrious footsteps of none other than John Wayne who, after completing several films here, donated picnic tables and barbecues so that others might also enjoy this fascinating scenery.

Ancient miners and astronomers

The archaeological site of Alta Vista, at Chalchihuites, 50 kilometres west of Sombrerete by paved road, seems to have been a cultural oasis, built and occupied by people who traded minerals far to the south, probably with Teotihuacan. Occupied more or less continuously from about 100 A.D. to 1400 A.D., Alta Vista is one of only a handful of such ceremonial centres in the vast semiarid north of Mexico. The site was an outpost of MesoAmerican settlement in an ecological and cultural frontier zone, where climatic changes caused continual shifts in the available resource base, discouraging most attempts at creating permanent settlements.

One of the major constructions at Alta Vista, the Labyrinth, is a sinuous walkway with pillars and turns, bordered by rubblework walls, and believed to have astronomical significance.

Silversmiths pray here

Continuing south towards Zacatecas, seven kilometres before Fresnillo is the paved side road to Plateros, a place visited annually by numerous pilgrims. The baroque Santuario de Plateros was built at the end of the eighteenth century as a suitable residence for the Santo Niño de Atocha and the Señor de Plateros, the patron saint of silversmiths.

Fresnillo, founded in the sixteenth century, has many old buildings, including the City Theatre, and several churches. Moreover, two very special, but very dissimilar, Mexican artists were born in or near Fresnillo in the same year: musician Manuel M. Ponce and painter Francisco Goitia. The Manuel M. Ponce museum houses a collection of the composer’s personal effects in a mid-nineteenth century Neoclassic building.

And so on to Zacatecas – through country which looked very different in the nineteenth century. What George Ruxton, a nineteenth century traveller, described as a day’s ride through “wild uncultivated country without inhabitants”, is now less than twenty minutes drive along a super-highway.

Where to stay: At the entrance to Sombrerete, the modern Hostal de la Mina (Avenida Hidalgo 114, telephone (493) 5-03-44) has good rooms but no restaurant. Several smaller, budget-priced, downtown hotels, including the Hotel Avenida Real, offer clean rooms and have restaurants.