A brief view of Jalisco ceramics

For me, Tonalá has always seemed like a magical sort of place, like something that one would only stumble upon in the make-believe world of fiction. Its narrow, dusty streets lined with unadorned buildings give Tonalá a rather unpolished look as compared with neighboring Tlaquepaque or Guadalajara’s downtown. Yet there are treasures to be discovered in almost every corner of this unpretentious Guadalajara municipality, which has long been recognized as a center for ceramics in Mexico. Artisan workshops and sidewalk stalls are filled to the brim with pottery and stoneware pieces that glisten under the glare of the sun’s rays, their shimmering hues tempting visitors to stop and take a look.

Tonalá boasts deep ties to the artisan tradition, as the history of pottery here dates back to pre-Hispanic times. However it is a place that does not easily give up its stories, as its people have learned to be mistrustful of strangers digging for information. “Suddenly, they don’t open their doors or don’t talk,” notes Prudencio Guzmán Rodríguez, who is in charge of the Museo Nacional de la Cerámica (National Ceramic Museum), which is located in Tonalá. As Guzmán explains, some of Tonalá’s residents “have been deceived and so they are wary.”

Thus, Guzmán says that it is up to him and the other museum workers “to bring our culture to the people who are really interested in it.” Guzmán sees the museum as a “link between Tonalá’s tradition and the people interested in researching our tradition.”

Indeed, the National Ceramic Museum traces Tonalá’s pottery tradition from pre-Hispanic times to present day, with approximately 500 pieces on display that range from clay artifacts to contemporary prizewinners.

The museum has had a close connection to Tonalá’s artistic community from its inception in 1986. In fact, local artists had a direct hand in the creation of the museum, as Guzmán explains.

“In the 1980s, a board of Tonalá’s artisans and businessman met and, in coordination with (local sculptors) Jorge Wilmot and Ken Edwards, they opened the Museo Nacional de la Cerámica,” Guzmán says.

The museum founders worked out an agreement with the Instituto Nacional Indigenista (National Indigenous Institute) to display pottery owned by the organization. Wilmot, who once lived in the two-story building that houses the museum, donated the artifacts. And the rest of the pieces resulted from el Certamen Estatal de la Cerámica (the State Ceramic Contest).

After a time, however, the museum board disintegrated and the state of the museum began to decline. Then came a period when the municipality’s administration showed little interest in the museum and thus didn’t give it much financial support, Guzmán says. Eventually, in 1995, the National Ceramic Museum was forced to shut its doors. As the months wore on, garbage began to pile up and the museum fell into a state of disrepair.

However, hope eventually arrived in the form of municipal president Jorge Arana. “He did everything possible so that the museum could reopen its doors,” Guzmán notes. “During that time, I was in charge of the rehabilitation process,” he adds. “We worked shifts from 8 o’clock in the morning to 8 o’clock at night in a very tiring, but satisfying, process.”

The museum reopened in 1996 and a decade later, it is still being improved in a manner that is painfully slow due to lack of financial resources. “The situation is difficult and sometimes sad… but we are people who love Tonalá very much,” Guzmán says. “So we are here imploring the gods of ceramics.”

One of Guzmán’s anticipated projects for the museum is to investigate each piece in the collection, which is comprised of more than 1,000 handicrafts. He then intends to create display placards with in-depth descriptions of each work.

“Right now, we are exhibiting so that people can come and see (the collection),” Guzmán says. “But we are not giving out information because we need to present real facts,” he notes, explaining that he wants to provide visitors with more than just superficial descriptions of obvious characteristics like the size and color of the handicrafts. Instead, he wants to delve into the history of each piece and extract all the stories that are waiting to be told.

Guzmán, who is a craftsman himself, already possesses extensive knowledge about the museum’s pieces and the artisans who created them. With him as my guide, the museum came to life with tales of the colorful characters who left their mark here in the form of pottery.

“I have always said that it is the artisans that I like, not the handicrafts,” Guzmán says with a laugh.

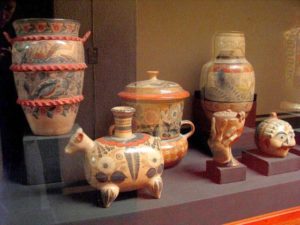

Pieces created by some of the area’s most renowned artisans are part of the collection, which encompasses all of the styles that are most typical to Tonalá. “The techniques that we have here are basically bruñido clay, bandera clay, petatillo clay and canelo clay,” Guzmán notes, explaining that these are the four methods most commonly used in Tonalá.

The bruñido or burnished style of pottery is thusly named because of the smooth, shiny appearance that this technique produces. This effect is created by polishing the piece with substances such as stone and the mineral pyrite.

Among the bruñido clayware on display in the museum are pieces that were crafted by Tonalá artists Salvador Vásquez and Juan Antonio Mateos. Vásquez worked with Wilmot, who is considered one of Tonalá’s pioneering artisans, and then passed his knowledge on to Mateos.

During my tour, Guzmán jovially recounted the tale of Mateos’ first days at Vásquez’s workshop. Apparently, Vásquez told Mateos to show up at 7 o’clock in the morning to begin his apprenticeship, so the eager pupil arrived on time and found the workshop closed. He sat outside for two hours, until Vásquez opened the door and let him in. The scenario repeated itself for several more days until the potter finally told Mateos to start arriving at 9 a.m. – the true starting hour at the workshop. A curious Guzmán asked Vásquez why he requested that Mateos arrive two hours early on those first several days. The potter responded that it was his test to see if the new student really wanted to learn. “Salvador is quite a guy,” Guzmán says, adding that Mateos turned out to be “the most outstanding of Salvador’s students – the best of them all.”

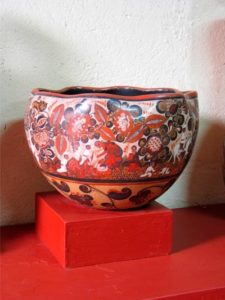

There are some similarities between Vásquez’ pieces on display at the museum and those of his former apprentice. For example, a Mateos bowl and a Vásquez jug that are on exhibit here both have portrayals of quotidian life in rural Mexico painted on them. These depictions of peasant figures at work and at play encircle both pieces, which glow with earth tone hues.

Of particular note are the decorative details, as both artisans have embellished their work with painted symbols that are characteristic of Tonalá pottery – the nahual and the flor de Tonalá.

Dating back to pre-Hispanic times, the nahual is a shape shifter who switches between human and animal forms and is often characterized as a shaman. Tonalá potters customarily depict the nahual as a large cat with a smiling face.

The flor de Tonalá (Tonalá flower) first appeared in pottery design in the early 1900s, according to Guzmán. Its distinctive shape is comprised of an oval center with rounded petals that form a scalloped design. Guzmán feels that this symbol “is what most represents Tonalá ceramics.”

Judging from the museum’s collection, the flor de Tonalá is indeed a popular symbol among local artisans. In addition to the bruñido clayware, the flower also appears on pieces in the museum’s bandera, petatillo and canelo acquisitions.

The bandera style of pottery is quite distinctive, as it is thusly named because of its red, white and green colors – the same colors that comprise Mexico’s bandera nacional (national flag). Red is commonly used as the background color, while the green and white are used for the decorative details.

Also easily recognizable are the petatillo pieces, which feature a painted crosshatch design as the background. As Guzmán explains, the name petatillo comes from the clayware’s painted white lines that crisscross each other in a style reminiscent of the woven straw mats called petates.

Among the museum’s petatillo ceramics is an urn and pedestal that were crafted by Gerónimo Ramos. Both pieces have a sun and nahual motif set against the characteristic crosshatch pattern. The focal point of the urn is a two-headed águila or eagle. Ramos’ pottery features a very fine pattern of petatillo, which Guzmán says is “one of the finest that is made nowadays.” A skilled craftsman, Ramos has won various accolades on the national level.

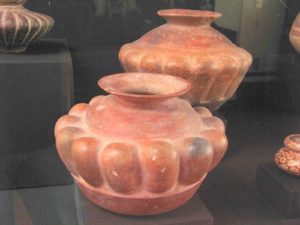

Another nationally recognized potter on display here is Nicasio Pajarito, who is considered a master of the canelo genre. He and his sons all use the canelo technique, which results in pottery covered in shades of canela, or cinnamon. “It goes through a bathing process in which the same color gives all of these tones,” says Guzmán, who explains that it is an engobe (liquid clay) bath that is used.

Aside from the aforementioned styles of Tonalá pottery, the museum also has betus and alta temperature clayware on exhibit.

Betus pottery is characterized by vibrant colors that give the ceramics a whimsical look. This style derives its name from the betus oil in which the clayware is immersed before it is fired in the kiln. The oil, which is made of a resin extracted from pine trees, gives the painted pottery a brilliant sheen.

A couple of the museum’s betus pieces, including a colorful ceramic church, were crafted by Candelario Medrano. This artisan, who died in 1986, achieved worldwide fame during his lifetime.

Guzmán told me a humorous anecdote about Medrano, who was always a small-town man at heart. Legend has it that Medrano won a contest in Germany and the organizer of the competition was so impressed that the artisan was invited for a visit. “It is said that Candelario Medrano responded, ‘yes, let’s go to Germany, but is it further than Guadalajara? If so, I’ll bring my hat,'” Guzmán recounts with a chuckle.

First introduced to Tonalá in the 1970s, alta temperature (high-fired) pottery or stoneware originated in Asia. Because stoneware pieces are fired at temperatures of 2,200 degrees Fahrenheit or higher, the glaze and the clay integrate to form a vitrified, nonporous surface. Stoneware “is a technique that Ken Edwards and Jorge Wilmot introduced to Tonalá,” Guzmán notes, pointing out that “they installed the first stoneware kiln in Tonalá.”

If visitors want to get a look at pieces by Edwards and Wilmot, they will find them in the museum’s collection of high-fire and low-fire plates housed on the building’s second floor.

There are a series of four plates signed by Edwards, which are decorated with whimsical bird and flower motifs that are characteristic of his work. All have been painted with delicate brushstrokes in tones of blue and brown.

Wilmot’s style is drastically different than Edwards, as evidenced by a plate decorated with a simple red figure reminiscent of pre-Hispanic art. Thick, fluid brushstrokes depict a strange creature with a serpentine tongue that sticks out between two tusks. It is standing upright on two legs and its two arms are thrown up in the air.

There are also a series of plates depicting the Stations of the Cross that have been signed by Wilmot and Salvador Vásquez. The plates illustrate the events leading up to and encompassing the crucifixion of Jesus Christ.

In addition to pieces made by Tonalá’s craftsmen, the museum also houses an extensive collection of ceramics from other regions of the republic. The national acquisitions represent pottery techniques from the states of Oaxaca, Guerrero, Chiapas and Puebla, among others. This section of the museum includes a varied collection of miniatures, as well as a massive and highly detailed arbol de la vida (tree of life) crafted by renowned sculptor Alfonso Soteno from Metepec, State of Mexico.

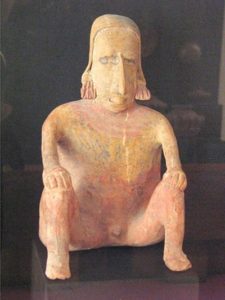

Also of note at the museum is the archeological display that features clay artifacts from Tonalá. Some of the pieces were actually found on the museum site, back when the building was being constructed as a home for Wilmot.

“There are lots of interesting things here,” Guzmán says. “The archeological pieces, the handicrafts, the nahuales – everything has its point of interest for getting to know Tonalá.”

I am interested in booking a tour with Guzmán for August 10, 2021. Would that be possible? I can be reached at [email protected]. This will be a group of 7 which will be celebrating my birthday. I am fascinated with Mexican pottery and my friends are too. I”m looking forward to hearing from you. Gracias!

Bear in mind that the article was published several years ago. You would need to contact the Museo Nacional de la Cerámica Jorge Wilmot directly: https://sc.jalisco.gob.mx/patrimonio/museos/museo-nacional-de-la-ceramica-jorge-wilmot Even without a formal tour, visiting the museum is a great experience. Happy Birthday! Enjoy your trip.

Thank you, Tony. I will contact Jorge Wilmont.

~ jeannie

Alas Jorge died in 2012, you are too late. hnlute

I cannot get through to book a tour for our group of 7. The telephone number listed is not correct. Is there a person (that speaks english) that I can call to do this? Thank you.

Jeannie, Sorry, but you now know as much as we do! I’m pretty sure you’d be just fine, given that your group is only small, just turning up and asking when you arrive about the possibility of a guide. Enjoy your trip, Tony.