Exploring Mexico’s Artists and Artisans

As a boy, Prudencio Guzmán Rodríguez was haunted by the mysterious characters known as Tastoanes, who are part of a tradition that spans more than a century in the municipality of Tonalá, Mexico, where he grew up.

The Tastoanes would come to Guzmán in a recurring dream, in which he was walking down the street and suddenly noticed that they were following him. Each time, he would enter his house and wait for them to pass by. “What made me scared was that instead of running by, they would wait there outside of my home,” Guzmán recounts.

Three decades later, this fear has been replaced by passion, as the 41-year old artisan is now a Tastoan himself. “Becoming one of them is how I overcame that fear,” Guzmán explains.

For more than two decades, Guzmán has been participating in the Tastoan tradition in Tonalá. Every July 25th, which is the feast day of Santiago (also known as Saint James the Greater), dozens of Tonalá’s male residents transform themselves into the legendary Tastoanes to partake in a performance that represents their struggle against Spain’s patron saint.

As Guzmán explains, the roots of the Tastoan performance can actually be traced back to the Spain of centuries past. “The performance of the Tastoanes comes from the 12th century, when the first performances were put on, known as the dance of the Moors and the Christians,” Guzmán says. In Spain’s version, the event symbolizes the expulsion of the Moors by the Christians, while Mexico’s variation — often called the dance of the Tastoanes — is commonly interpreted as the representation of the Spanish conquest of Mexico in the 1500s.

Some say the term Tastoan is actually derived from the Nahuatl word Tlatoani, which means lord or spokesperson. Thus, the present-day Tastoanes represent the indigenous leaders who resisted the Spaniards during the conquest.

“I greatly identify with the warrior who opposes the conquest, with the warrior who opposes the Spanish invasion in Mexico,” Guzmán says.

“For me, a Tastoan is like a type of primitive instinct that is asleep all year,” Guzmán notes. “But when the date draws near, it wakes up and starts to prepare for one more battle against Saint James (San Santiago).”

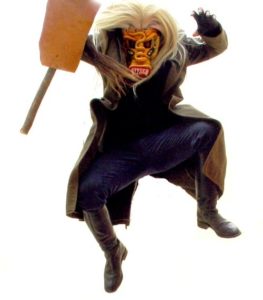

As Guzmán explains, the males who participate as Tastoanes in the annual event undergo a transformation of sorts when they dress for the performance. “They are in their masks and fixing their wigs… and I see them with a different spirit,” he says. “They are no longer themselves, they are now the Tastoanes.”

Indeed, the original identities of the Tastoan performers disappear the moment that they don their masks, which are an integral part of the tradition. Originally, the Tastoanes crafted their masks of clay, says Guzmán. But due to the fragility and heaviness of the clay masks, this material was eventually replaced by leather.

Other aspects of the mask creation have changed as well, as Guzmán explains. For instance, the masks were previously painted with anilines and now are painted with acrylics. “The pieces that they make now are really more refined. The others were very primitive,” Guzmán says.

“But there was a custom that I liked a lot that has already been lost,” Guzmán adds. That custom involved the reuse of the mask’s base from one year to the other. “They would throw the masks in a container with water and start to pull off all the parts — the nose and the eyes,” says Guzmán who recounted that new masks would then be created from the bases. “I really liked it a lot because it was like killing one Tastoan to give life to another one,” he says.

Nowadays, it is customary for the performers to craft completely new masks each year, some of which are entered into a local contest, known as the Concurso de Máscaras de Tastoanes de Tonalá. Guzmán won first place in the contest when he first competed in it about 20 years ago and since then, he has placed an additional 10 more times as either first, second or third.

Guzmán’s creations have also gained recognition on a national level, as he has been awarded one second place and two third places in the masks category of the nationwide contest, El Gran Premio de Arte Popular, which he has competed in since the year 2000.

A skilled craftsman, Guzmán has been immersed in the artisan world since he was a young boy. “At the age of five, I was already making little things,” says Guzmán, who learned about pottery from his father. Both Guzmán’s father and grandfather created ceramics in the canelo style, which is characterized by the shades of canela or cinnamon that it produces in the finished pieces. Although both men have passed away, Guzmán and his five brothers are continuing on in the artisan tradition.

Although Guzmán dedicates full-time hours to Tonalá’s Museo Nacional de la Cerámica (National Ceramic Museum) that he heads up, the artisan also finds time to work on his handicrafts. His current pieces include a series of Madonna-like ceramic sculptures, as well as ceramic lamps encrusted with glass.

The Tastoan masks and sculptures that Guzmán creates, however, have a significance to him that goes beyond the artisanal aspect. “It is not like making a barro bruñido piece or petatillo or barro canelo, says Guzmán, talking about three of the main traditional pottery techniques in Tonalá. “No, it is like something living.”

“I have the idea, which is perhaps a little romantic, that a mask (is made) how it wants to be,” Guzmán explains. “I feel like a type of door to another world – I am a door through which these characters enter and arrive.”

When creating the masks, Guzmán even begins shouting in the same manner that the Tastoanes shout during the yearly performance. “There is a shout that is spontaneous, like a growl… and when I make my masks, even though I am alone, I start shouting like this unintentionally,” Guzmán says. “It is like a display of happiness, of pride.”

Guzmán recounts how he was once working on a Tastoan sculpture while alone in his house and some relatives walked in while he was shouting to himself. “My niece said to me, ‘One day you are going to go crazy with your Tastoanes and I’m going to find you talking to them,'” Guzmán says. “And I told her, ‘The strange thing is that you are not going to find me talking to them. You are going to find me listening to them because they are going to be speaking to me.'”

“They do speak to me in a way,” Guzmán concludes. “It is like a communion of sorts with these beings, with these warriors.”

For Guzmán, the Tastoan tradition is a part of him all year long and not just on the day of the annual performance. He is constantly researching the history of the Tastoanes, as well as the events that unfolded during Spain’s conquest of Mexico. From the moment Guzmán became involved in the annual event of the Tastoanes, he began investigating its roots. “I began researching exactly what a Tastoan is, what he represents and where he comes from,” the artisan says. “And from there, I started forming my own ideas and my own conjectures.”

Guzmán has actually incorporated some of his findings into the masks that he creates. He recalls one instance in particular, when he found some letters that were sent from a scribe who described how the indigenous warriors acted during a battle in Tonalá.

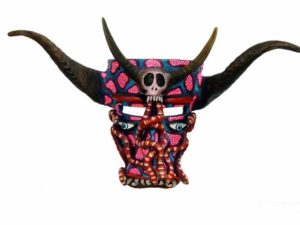

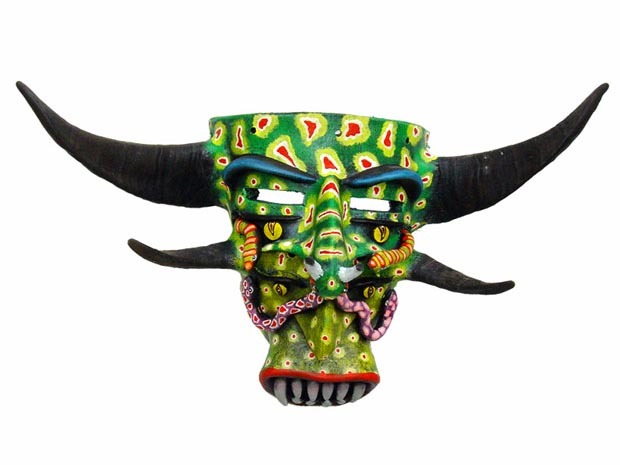

“The scribe said that the indigenous people of this region were so fierce in battle that he saw one indigenous warrior who had been wounded by a spear on two occasions and yet continued to fight against a Spanish warrior who was on horseback,” Guzmán recounts. “He said that they were so fierce that they appeared to be demons.” Upon reading that description, Guzmán decided to begin putting horns on his mask.

Some of Guzmán’s masks also have small dots on the surface, which symbolize the smallpox disease that the Spanish conquerors brought with them to Mexico. “Together with syphilis, smallpox was among the greatest imports from Spain to our territory during the time of the conquest,” Guzmán notes, laughing wryly.

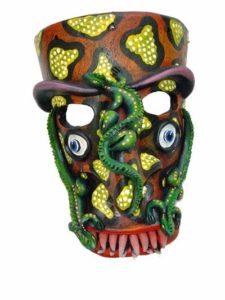

Additionally, many of Guzmán’s masks have sculpted creatures such as snakes, scorpions, spiders or lizards on them. These creatures also are reflective of Guzmán’s research, as he has read that the indigenous warriors fled the Spanish conquerors and hid in caves, where they were then discovered dead with the aforementioned animals crawling on their faces.

“Each one of my masks tries to carry a message,” Guzmán says. One mask in particular has a very touching story behind it. The mask is called ” El Clonador” (The Cloner) and it is covered with about seven sculpted snakes that are each wearing a smaller replica of the actual mask. Guzmán says that he made the mask in honor of the students who he taught in a Tastoan workshop more than a decade ago. “They have a special place in my heart,” he says of his former students, some of whom are now active in the Tastoan performance. Guzmán happily passed on the Tastoan tradition to his students, including teaching them how to act in the performance and how to create their own masks.

For Guzmán himself, the creation of a mask can take from as little as four days for a simple one to as much as two weeks for an elaborate one. Guzmán forgoes the fragile ceramic masks for the Tastoan performances, choosing to use the sturdier leather ones instead. When crafting a mask, Guzmán starts with a base of vaqueta (cowhide) and starts sculpting the different shapes of the Tastoan’s face out of a paper paste. He then paints the piece entirely black and applies colored acrylics over this base coat, using a technique in which he puts the barest amount of paint on the brush and then scrapes the color onto the mask. “It is more like engraving than painting,” he says of the process.

He hopes to one day teach his own sons, César Aldair and Adán Israel, about the Tastoan tradition. The two boys, who are just one and three years old, have already shown interest in the masks. “From the time that they could pick things up, they have lifted the masks to their faces,” Guzmán notes. He has already bought them future wardrobes for the Tastoan performance and hopes to one day make them their very own masks. “In 10 or 15 years more, I am going to make them some very special masks… (but) first they will have to make their own masks,” Guzmán says.

“I hope that some day the children of my children will keep fighting against San Santiago – that is my great hope,” Guzmán notes. He loves how the Tastoan participants, who usually number around 60 in total, range in age from as young as six to as old as nearly 100. It is a tradition that spans generations, as Guzmán explains.

“I came to a conclusion, which is very much my own conclusion, that the Tastoan was turned into a wandering warrior from the time that he fled the battle,” Guzmán says. “Thus far, we continue to confront San Santiago. We are a type of warrior who is condemned to fight all throughout life, all throughout the duration of the world.”