Exploring Mexico’s Artists and Artisans

Tucked away between the towering hotels of Cancun’s sparkling shores is a cultural treasure known as La Casa del Arte Popular Mexicano. Perched atop the pier on Kukulcán Boulevard in Cancun’s hotel zone, the tiny museum is brimming with handcrafted pieces that reflect Mexico’s rich artistic legacy.

Careful thought went into the creation of La Casa del Arte Popular Mexicano, which opened in 2001. It was founded by architect Miguel Quintana Pali and his sister Guadalupe Quintana Pali, who currently serves as director of the museum.

“They have always had a lot of interest in promoting what is Mexican and maintaining our traditions and culture,” explains staff member Gabriela Padilla de la Parra, who is in charge of both the museum and its attached shop. “When they decided to set up the museum, Guadalupe traveled throughout all of Mexico collecting pieces about the themes into which the museum is divided.” According to Padilla de la Parra, the director traversed Mexico for two years, amassing hundreds of artisanal pieces that are now on display.

The pieces are divided into categories to reflect different styles of Mexican folk art, the diverse regions where the handicrafts are made and the multifaceted cultural beliefs that inform the artwork. English-language cassette tours of the museum are offered at the front desk, providing visitors with a glimpse into both the use and significance of the pieces on display.

One eminent theme that manifests itself in a number of pieces is the concept of death and its place in Mexican culture. Artistic portrayals of skeletons and skulls abound. Upon entering the first room of the museum, visitors will see a life-size sculpture of a skeleton with long blond braids, sitting in a dainty blue chair. Along the wall to her left hang dozens of masks, including ones carved and painted to look like skulls. As explained in the tour, the masks represent a variety of diametric concepts, of which life and death and the balance between them are of utmost importance.

“Its representation began in the pre-Hispanic times, since its philosophy is based on the fact that without death, there is no life,” according to the tour script. “That is why the continual representation of death in various forms is an element of daily life in which one lives with the dead as if they were alive, especially on the days when it is customary to remember them. The Day of the Dead – a true fiesta.”

Indeed, Day of the Dead (known as Día de los Muertos in Mexico) is a perfect example of how death is represented through artistic expression in regions all across the country. On November 1st and 2nd, private households and public venues alike display altars that celebrate the deceased, who supposedly return to the world of the living on those two days each year. This annual tradition of altar making gives Mexican people from all walks of life the opportunity to reflect upon their departed loved ones, as they decorate the altars with photos of the deceased and display their once favorite foods and drink.

La Casa del Arte Popular Mexicano planned to commemorate Day of the Dead with an altar contest open to all ages on October 31st, but the event was cancelled due to the damage in the region caused by Hurricane Wilma.

The museum holds various contests throughout the year. This is an invaluable way of keeping local residents in touch with Mexico’s artistic traditions. In addition to the art contests, La Casa del Arte Popular Mexicano also organizes an annual fair where artisans from different states of the republic sell their wares. And the museum staff plans to offer workshops for children where they will learn how to crafts pieces such as piñatas and masks.

Education is a prime focus of the institution, as part of its mission is to teach local children about the culture found in other parts of the country. “The children are very important,” Padilla de la Parra says. In the first quarter of 2005, a total of 2,917 youngsters passed through the museum, which currently focuses solely on schoolchildren from Cancun. According to Padilla de la Parra, the museum staff hopes to soon give tours to youngsters from the entire Riviera Maya region.

Whether young or old, however, visitors are sure to come away from La Casa del Arte Popular Mexicano feeling rewarded.

Much like the Day of the Dead traditions, many of the museum’s pieces reflect the duality of Mexican culture, which has its roots in both Spanish and indigenous customs.

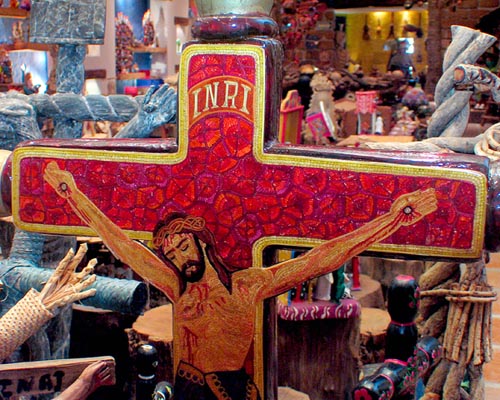

For example, the museum boasts an extensive collection of religious-themed art that speaks to the pervasive presence of Catholicism in Mexico. According to the tour script, Mexico “got the Catholic religion from the Spanish conquerors; it became a pillar of its idiosyncrasy and customs which were born from the root of the mestizaje – the mixture of two cultures.”

This Catholic influence is reflected in the diverse array of nativity scenes, crosses and miniature churches displayed in the second room. This collection also captures the variety of techniques that are utilized, as each piece has a distinct style that is characteristic of the region in which it was created.

The nativity scenes include pieces from Oaxaca sculpted from the region’s famous red and black clays, as well as one from the Yucatán comprised of figures painted on clay bells with the baby Jesus sitting in a miniature green hammock. Another nativity scene captures the ironic sense of humor that some female artists from Michoacán reveal in their work, as the figures in this piece are depicted as fanciful devils.

The cross collection contains pieces by Huichol artists from Jalisco and Nayarit, in which colorful beads form intricate designs that cover the entire surface of the cross. Other distinctive works from this collection include one from the state of Mexico fashioned of tiny pieces of straw, which have been painted with aniline dyes to form the figure of Jesus. Another cross, crafted in Guanajuato, features bottle caps with cutouts of different religious figures.

The miniature churches also showcase a similar variety of regional techniques. One dazzling church from Guerrero is made of lacquered wood with vivid flowers painted on it and a divine eye protruding from its roof. Others from the state of Mexico are also quite festive, due to the vibrantly colored clay from which they have been sculpted. And another from Oaxaca utilizes the filigree technique, in which the clay church has been overlaid with an ornamental pattern of flowers affixed petal by petal.

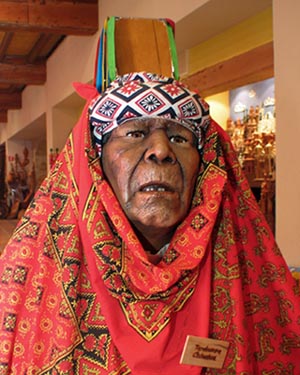

The religious motif found in the museum’s collection of nativity scenes, crosses and miniature churches finds further expression in the recreation of a church scene that has been set up in the back half of the second room. Lifelike figures are posed among wooden church pews and dressed in traditional gala costumes from various regions of the country, including Chiapas, Guerrero, Michoacán, San Luis Potosí, Chihuahua, Oaxaca, Puebla, Hidalgo and Campeche. Many of the outfits feature intricately embroidered clothing and ornate head attire.

Here again, we see the coexistence of indigenous and Spanish beliefs, as a shaman is among the figures gathered in the pews. He wears a mirror on his head to ward off evil spirits.

All of the churchgoers have actually been created in the likeness of real people that Guadalupe Quintana Pali met during her travels through Mexico, according to museum staff member Olivia Carranza. “All of these people really exist,” Carranza says. The figures face an altar that takes up the room’s entire back wall. Its focal point is a hollow cross filled with candles that has a representation of Jesus hanging from it. The roughhewn look of the cross is contrasted by the colorful and detailed craftwork that fills the rest of the altar.

Many of the altar pieces depict the Virgin of Guadalupe, who is the patron saint of Mexico and of the Americas. These images are made from many different materials, including papier-mâché, clay, wood and ceramic. Some show the dark-skinned Queen of the Heavens in a traditional manner, standing on the moon and wrapped in a cloak sparkling with stars. Other depictions are colorful seed bead renderings by Huichol artisans that were crafted especially for La Casa del Arte Popular Mexicano. And once again, a skeleton makes her jovial appearance, as one artist uses the image of death to represent the icon of Mexican Catholicism.

Skeletons also pop up in the other collection of altar pieces, which are sculptures known as Arboles de la Vida (Trees of Life). These decorative handicrafts originated as candelabras depicting the Biblical story of Adam and Eve. Over time, however, they have evolved into elaborate sculptures that focus on themes ranging from the cyclical seasons of the year to the singular seasons of life. One Tree of Life on the museum’s altar traces the escapades of a skeleton named Tiburcio, starting with his birth and ending with his death.

Additional Trees of Life also incorporate skeletons into their visual narratives. In one such sculpture, a typical Mexican market is portrayed, with dozens of skeleton merchants and skeleton shoppers shown haggling, laughing and gossiping. There are even some skeleton dogs that appear wander the market, with one trotting about with a sausage in his mouth.

Along this same wall are also several glass-front dioramas, with one showing miniature skeletons enjoying themselves at a bar. Great detail has been incorporated into the scene, down to the sayings stuck to the walls, such as one rhyme that reads “El agua para los bueyes, pulque para los reyes (Water for oxen, pulque for kings).”

Depicting death in situations of the living is an artistic tradition for which Mexico is renowned. This legacy and other artistic customs live on for all to enjoy at La Casa del Arte Popular Mexicano, which also features toys, musical instruments and gourds among its varied pieces. It is the mission of the museum to preserve the country’s unique craftwork, as Carranza explains.

“One of the interesting points about the museum is that the owner (Guadalupe Quintana Pali) visits los pueblos in order to shop,” Carranza says. “She buys from the artisans with the motive of not letting our craftwork disappear; supporting them so that they can continue working.”

. . . . .

As this photograph reveals, damage to the museum from Hurricane Wilma was not as bad as we feared. Photo by Erin Cassin.