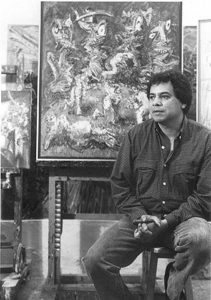

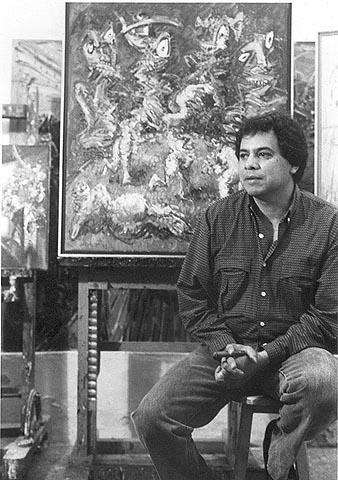

For the Mexican painter Javier Vasquez, painting is performance – a performance done to jazz. As he paints, his hand and brush flash across the canvas, echoing and replicating in paint the rhythms and riffs of the music. He works with the intensity and spontaneity of the action painters of the 1950’s, but for him it is the jazz that animates his actions, as if his hand is directed by invisible lines of force. The music is essential to his art. Whether painting in his studio or giving a live performance on stage with a band, which he often does, it is always there.

He calls himself Jazzamoart, a name compounded of the passions of his life: jazz, amor, and art. He took this name at the age of 20, when he first began collecting jazz records and painting to them. In those days he was selling generic scenes of Mexican life on the streets of Mexico City, but since then he has become a major figure in the Mexican art world.

Early in life Jazzamoart developed a passion for art and music. His father, a poet, had a deep love for the music of the big band era – Miller, Dorsey, Ellington – and Jazzamoart grew up in an atmosphere filled with creative activity. He recalls that the family house was a gathering place for artists and writers.

“I remember as a small boy sucking on chocolate cigars while my father and his friends smoked and drank and talked. The house was always full of cigar smoke, laughter and, of course, the music.”

A good cigar, no longer chocolate, is still a constant companion. “Life,” he says, “was like a game–but a serious game.” It was an environment designed to draw out whatever creative abilities a young boy might have. Jazzamoart’s father recognized early on that there was something special about his son, and gave him his own studio when he was six years old. Since then he has always had his own space to work.

The influence of jazz is evident in every aspect of Jazzamoart’s painting. He admits that he is a compulsive collector of records, having bought at least one every week for the last 25 years, building a collection that many jazz radio stations would envy.

“I try to capture in paint the sounds and images of the music and the personalities of the musicians,” he says. His collection is wide-ranging and current, but his favorites remain the classics of the bebop era: Charlie Parker, Miles Davis, John Coltrane, Thelonius Monk.

“New Orleans jazz is too relaxed,” he says. “It lacks intensity.”

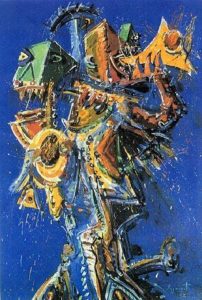

The high energy and spontaneity of bebop fit perfectly with Jazzamoart’s approach to painting, which is rapid and gestural. His movements are so informed by the music, that as figures materialize on the canvas the energy and spirit – the sound – of the music is present in every squiggle and brushstroke. Most of his jazz paintings have a jagged, nervous quality about them. Saxophones are painted like yellow bolts of lightning, figures are on the verge of flying apart, musicians and instruments are barely contained yet so energized that one feels at any minute the whole thing might go careening off into space. There are calmer, more tranquil pieces, especially some of the nightclub pictures, but it is the sense of expansive energy straining at its limits that for me is the most powerful feeling evoked by this man’s work.

The catalog for a one-man show held at Mexico City University in 1993 identifies Jazzamoart as ‘El Inventor de Ruidos’ – The Inventor of Sounds. This is also the title of the first painting in the catalog, a picture of either three musicians playing saxophones with the sound pouring from the instruments as squiggly drips of red paint, or a picture of one musician with three heads each playing a saxophone, a sort of Picassoid Rahsaan Roland Kirk. Although Jazzamoart’s work is figurative, his art is as much about the abstract quality of sound as anything else. El Inventor de Ruidos.

Jazzamoart has such a reverence for the great jazz players that he says he feels humble and intimidated in their presence. He laughs as he tells of a recurring dream in which Charlie Parker is waiting for a taxi on a New York street, while he, Jazzamoart, stands and watches from the doorway of a jazz club, afraid to speak to him. “Musicians often appear in my dreams,” he says. “But most often, Charlie Parker.”

The saxophone is Jazzamoart’s fetish, the instrument that appears most often in his work. “It is very sophisticated, sensual,” he explains. “Like a sculpture.” He collects saxophones and plays a little himself, though he confesses that he is not very good. But he is proud of his oldest son, also named Jazzamoart, who plays very well and has toured with bands in Latin America, the United States, and Europe. Even though he downplays his own musical abilities, Jazzamoart enjoys playing the drums with pickup bands made up of his friends.

Though jazz is the most obvious wellspring of his inspiration, Jazzamoart also draws on a rich fount of sources in both art and life. Nothing escapes him. Asked what feeds his art, he will reel off in the same breath his family, music, Picasso, the bullfight, the cabaret, soccer. His life as an artist and as husband and father is seamless. He lives in a two-bedroom apartment with Nora, his wife of 27 years, and his three sons. Across the street is his studio, his father’s apartment, and his brother’s music studio. It’s all of a piece. At a gathering in his apartment, he’s likely to disappear at any moment. “Where’s Javier?” someone asks. “In his studio,” says Nora. Something has given him an idea.

“Every day is a surprise,” Nora says. Javier thinks life should be an improvisation, like jazz. He does not carry a daily planner. “Of course,” she adds, “In daily life you have to do the same things as all people, but you are more at the whim of the artist’s thoughts and ideas. Having children with an artist is a challenge. The art is always on his mind. But he is also a very loving father, not the selfish artist type.”

It is Nora who manages the business and provides the solid ground of daily life. She does the driving, a rarity in machismo Mexico; Javier, by choice, has never learned.

Javier is off to a soccer match with his eldest son. “Who’s playing?” I ask. “I don’t know,” he says. “It doesn’t matter. It’s the atmosphere I go for. The environment.”

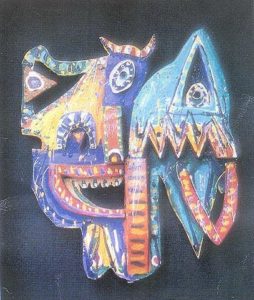

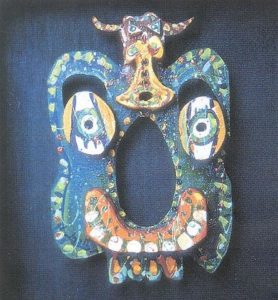

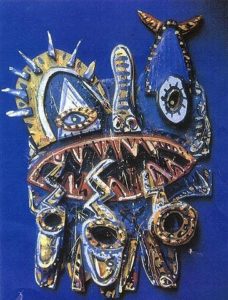

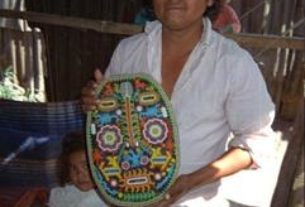

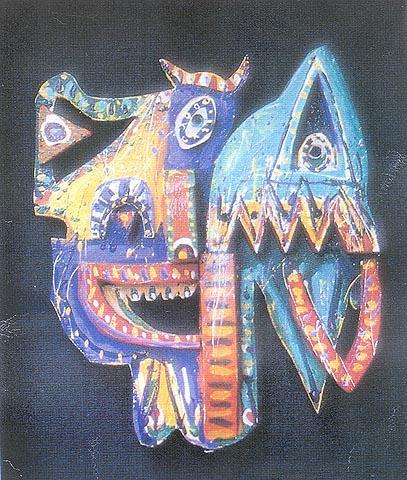

As a Mexican, Jazzamoart has inherited a deep love for the art of his country: everything from folk art–particularly masks–to the great Mexican modernists. One day my wife and I walked with him through the vast craft market in Mexico City. His eyes took in everything, and he picked up one object after another–a vase, a horse and rider woven from reeds, a brightly painted dish–commenting on their artistic merit, delighting in the playfulness and skill of the craftsman. But it doesn’t take more than a quick perusal of his work to see that from his Mexican heritage it is the mask that has grown the deepest roots. The mask itself is a recurring motif, and in the jazz paintings the faces of figures frequently possess mask-like features.

More than anything else in Jazzamoart’s work, these mask faces reveal a vital fusion of Mexican and European influences – what might have emerged had Picasso been a Mexican maskmaker. He acknowledges a debt to the great European modernists, particularly Picasso, Van Gogh and Sanda; and he has also drawn from Mexican painting of this century: the color of Rufino Tamayo, the expressionism of Cuervas, the murals of Orozco. All of these influences thread their way through Jazzamoart’s work, but it is, finally, the music that binds them together and infuses them with his own original vision. Cubist dislocations seem to emerge naturally from the edgy, nervous energy of a Coltrane solo.

Jazzamoart’s use of mask faces discloses another of his recurrent themes: a playful – seriously playful – interest in the multiplicity of human identity. For Jazzamoart, life and art are a matter of improvisation, each moment invented as it comes. The self, like a jazz solo, is in a constant state of transformation, always on the edge of dissolving and reforming. The painter’s way of working is part and parcel of this vision. He works with lightning speed, much like an action painter–quick, improvisational, gestural. He is catching life on the fly, rendering passages of time that will never be repeated.

Saxophonist Joshua Redman has written, “The magic of the jazz experience is in its irreplaceability. Every sound is precious because it will never again be played (or heard) in precisely the same way, at the same moment, in the same place, with the same feeling.”

Jazzamoart might have said the same about his own life and art.