Mexico Design & Style

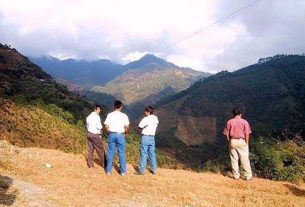

In the late ’90s we became captivated by the richness of the Yucatan region’s hacienda architecture and the history of its multilayered civilizations. Trailing through myriad Maya villages and down overgrown dirt paths, we encountered many hacienda revivals in full force, as well as dormant treasures untouched by modern hands. While researching our second design book, The New Hacienda, the idea of rescuing a hacienda from ruin and bringing it back to life took firm root – we were on a quest for a colonial hacienda that showed potential for restoration.

In early 2000, Hacienda Petac found us. An 18th-century estate in close proximity to Mérida, Hacienda Petac was a colonial cattle hacienda before its conversion to a henequen plantation in the late 1800s. Unlike many of the peninsula’s haciendas that were altered over time, Petac’s architectural integrity was surprisingly intact, without any 20th-century alterations. The fact that Petac predates many Yucatan haciendas that were built during the henequen boom of the late 19th-century endows the estate with a rich colonial history. The juxtaposition of the colonial casa principal to its later-built 19th-century casa de máquina created a unique testimonial to Yucatan’s diverse hacienda epochs.

Despite its critical need for a new roof and massive facelift, Petac’s potential for revival was immediately apparent. We saw a jewel in the overgrown jungle – rich in original architectural elements and design details that had been essentially unaltered through time: baroque stone entrance arches, stucco ornamentation, exquisite Moorish-style arcades, interior wall stencils and hand-turned spindles on windows and doors. A stone lime kiln once used for making lime plaster and stucco was also intact. The property was comprised of numerous worker’s buildings, a chapel, water storage tanks, and a stone aqueduct system once used for orchard and field irrigation. The presence of some existing infrastructure (water, electricity, good roads) was an added attraction. The combination of these unique elements on a single property prompted us to consider the hacienda’s value as a future showcase for Mexican design and hacienda restoration.

In the spring of 2000, we teamed up with fellow Mexico enthusiasts, Dev and Chuck Stern to partner a future for Petac. As a foursome, our shared passions for Mexican history elevated the project into a dream in the making. From the beginning, our vision was to preserve Petac’s architectural legacy. We wanted to create a venue for educating homeowners and designers in the spirit and details of an authentic 18th-century hacienda, while also forging a comfortable retreat that would hail the original richness and splendor of the Yucatan lifestyle. To these ends, we have sought unique antiques and elements that would best echo the hacienda’s origins and reflect its rural surroundings. We imagined a place where homeowners and designers could come to discover architectural restoration and building techniques, Mexican antiques and local design resources-all a step away from the estate’s luxurious pools and gardens.

With these goals in mind, we devised an overall vision for the property that would accommodate our dual missions. The casa principal would be used as a library and as common space for entertaining and dining. The machine house would be renovated for guest suites, an owner’s apartment and a 1,200 square-foot billiards room. Additional guest rooms and Mexican Design Center would be housed in revitalized buildings adjacent to the casa principal. The nearby village was a significant asset in the plan, providing local labor and staffing for hacienda projects.

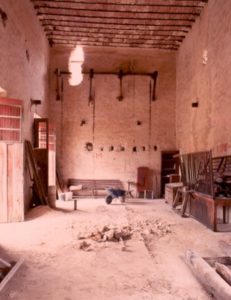

Clean up and restoration

In June 2000, initial work began with extensive clean-up and careful evaluation of what elements would be salvageable for reuse during the restoration. Original paint colors were excavated and old beams, wood, stone and iron were meticulously sorted and stored for later use. Doors and spindled window-guards were cleaned and restored with special finishes, and traditional cement tiles were selected for floors. We established a comprehensive interior design plan for the casa principal that would be true to the hacienda’s roots and evoke a luxurious timeless air. Traditional design elements were sought that would establish an air of authenticity and reflect the country setting. In keeping with the belief that it is color and architectural detail that truly furnish a room, the interior design focused on accenting rooms with simple colonial antiques and santos to achieve an understated elegance.

Architect Salvador Reyes Rios, in partnership with a group of architecture and restoration professionals, worked with us to orchestrate and fine-tune the hacienda’s new presence. The foundation for all the architectural design and engineering work was the maintenance of balance between historical restoration and modern adaptation. In addition to restoring the roof and installing air conditioning, technical issues included updating electricity and plumbing. The restoration plan integrated many traditional methods and masonry techniques, including the use of cal (lime-based paint) and ancient Maya stucco finishes.

The roof restoration spanned three months and required removal of its original fifteen inch packed lime-and-stone base. As the old roof surface was removed, it expanded, eventually yielding a 3-foot deep refuse field of caliche that became the base material for a porch extension on the back portal. Removal of the original stone exterior’s weathered stucco and careful restoration of its chinked-wall surface (rajueleado) was a 6-month project. Technical issues included updating the electricity three times to accommodate air conditioning and a system of wells dependent on electrical pumps. The plumbing required new wells and septic systems in addition to five miles of pipes and trenches to support new bathrooms and garden irrigation. Despite the enormity of the task, the long-term restoration project proceeded, thanks to the fortitude of a partnership enchanted by the old-world charms of Hacienda Petac.

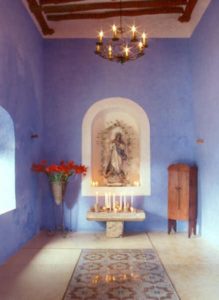

Sharing the partners’ interest in creative reuse and salvage, Reyes and his group devised innovative solutions that would employ existing elements. To support the shade-giving pergola, creatively designed to extend over the pool surface, old round beams were installed as posts, enabling sun cover for the hammocks that dangle just above the water. Another massive beam and corbels found in the casa de máquina were recycled for decorative use above the kitchen counter. The colonial-patterned tiles discovered in one room of the casa principal were an assembly of useable and damaged cement tiles. Wanting to preserve this colonial-patterned tile as a testament to the hacienda’s decorative past, the pattern was replicated and new molds fabricated. The original useable tiles were moved to the casa principal’s chapel and laid in a central field surrounded by a polished cement floor.

Addressing the placement of soothing water features was vital for surviving the Yucatan’s tropical climate. First, the estate’s former water storage tank was converted to a swimming pool and surrounded by a shade garden of native ferns and tropical plants. Original wells and aqueducts were retooled to feed the corral’s 40-foot bebedero (water trough), which now splashes water from multiple stone caños (spouts) in a fountain display.

For the casa de máquina, Reyes reconfigured the building into three spacious guest suites and an entertainment/billiards room. Outside, a lily pond was designed to surround the old chimney, as well as a 36-foot long water feature inspired by the water channels that once fed the orchards. Lined with Maya chukum stucco, a tree-resin blend noted for its permeability and natural translucence, the fountain’s trickling water circulates from an elevated water chamber to a second source at ground level.

Interiors

Although modest in size, the hacienda’s casa principal is a grand space with high-beamed ceilings, thick walls, and doors opening onto two portales that overlook the main corral and gardens. A simple yet richly inviting room, the long, narrow central sala features melon-hued walls, deep-blue wainscoting and mint-green cement floor tile. The warmth is echoed in the antiques and furnishings crafted from tropical woods. For the custom furnishings, special attention was given to choosing fabrics and leathers that evoked a modest gentility, thus blending well with the older elements. The sala’s narrow-width, multiple doors and protruding hammock hooks presented a design challenge for positioning furniture. In addition to a 9-foot sofa, a narrow coffee table offered an appealing spatial solution, as did the custom mirror that accentuates the room’s elongated shape.

The design of Petac’s kitchen projects an admiration for traditional Mexican cooks and cuisine by featuring a collection of Mexican culinary antiques and offering an inviting space for regional cooking demonstrations. Bright yellow walls surround a rebuilt counter covered with colonial-style Talavera tile. A recycled beam and corbels, original to the hacienda, rest above the colorfully tiled counter. Dressing up the space with a utilitarian touch are old Maya metates, sugar molds, a hand-carved coffee mortar, gourd-bowls, and a repisa (hanging shelf) for displaying glasses. A pistachio-painted copeti discovered in Merida has become a welcome “working” art object, reemployed with the addition of hooks for utensil storage. The kitchen’s original 18th-century treasure is an alacena, or built-in wall cabinet.

The original paymaster’s office featured a unique wooden grille that was adapted to become a decorative feature in the casa principal’s bar. Once a secure booth complete with a small window for money transactions, hacienda workers would receive their wages from their paymaster. In its original position, it divided a room in half and blocked traffic flow. The old booth was restored and newly positioned to form a central focal point for the custom-designed cocktail table.

One of the highlights of Petac’s restoration was the discovery of a small chapel in the casa principal. The former owner intended the space for use as a bathroom. Only after our restoration began on the walls did the space reveal a plastered-over nicho in the center of the room. As its position was a profound clue to the room’s original sacred use, we chose to restore the space as a chapel. Soon after, serendipity was with us in our discovery of a rare santo – perfectly sized to fit the tall nicho space. The blue hue of the hand-painted Virgin’s robe was the same hue as the room’s original paint, detected in the window jambs. Perhaps it was a coincidence, or perhaps, as we like to think, the color scheme of the original architecture and relics of this space was already perfectly worked out, just waiting to be brought to light.

Hacienda Petac is open as a luxury vacation rental. For information: www.mexicanstyle.com or call (512) 327-8284.

Hacienda Petac is featured in two of Carr/Witynski’s design books: Casa Yucatan (2002, Gibbs Smith Publisher) and Mexican Details (2003, Gibbs Smith Publisher). Preview

How did you find the property itself?