Juan Mata Ortíz is a small village of potters, farmers and cowboys in Northern Chihuahua. About 30 years ago, an unschooled artistic genius, Juan Quezada, taught himself how to make ollas, earthenware jars, by a method used hundreds of years ago by the prehistoric inhabitants. Now, his works are known worldwide and over 300 men, women and children in the village of less than 2000 make decorative wares. Much of the polychrome and blackware is feather light and exquisitely painted.

Many of the potters are also cowboys and farmers. These stories serve to document the art and the people in this unassuming pueblo, an art that is often called “magical” by the relative handful of tourists who visit. Enjoy this other view of Mexico.

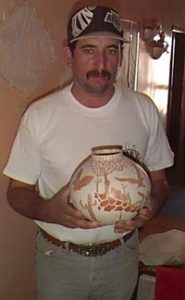

The ram, a Big Horn sheep, stands atop a pile of rocks and stares down at a poised mountain lion and a scattering of scorpions, squirrels and iguana. The puma is crouched, ready to leap past a prickly pear onto the back of a proud stag. Nearby, a wolf lurks behind a century plant which reaches from the low shoulder of the white and red ceramic to the curved rim.

This is only part of the scene incised on Leonel Lopez’ greatest work.

On the other side of the 14-inch high clay pot, two red wolves bay at another century plant, while below rabbits and squirrels scamper about, unconcerned. Beneath the shoulder, a river swirls around the circumference until it falls in a cascade to a small lagoon, which forms the design on the base of the jar. By following the river, one can encounter an unlucky swan struggling in the jaws of another wolf.

Words cannot describe the olla–it needs to be seen. Like all of Leonel’s works the last few years, this one started with the purchase of an unfired whiteware olla from potter Tomás Asuna. Leonel first sanded and polished the piece. Next, he covered the whole surface with a red slip. Finally, came the artistry as he used a jacknife and dental tools to create an incredible collection of wilderness scenes in the sgraffitto style.

“I love to carve all kinds of animals,” he told me. “Rams, scorpions, fish, birds, butterflies. And the outdoors–trees, cactus and rocks.” Two other ceramic jars sit nearby, both are covered with incised lizards crawling up and over the pots. On one, the slip is black, on the other red. In each case, the pot is first covered with either a red, black or cafe-colored slip, then the design is painstakingly carved.

I first met Leonel in 1990. He rode with local artist Roberto Banuelos and myself into the Sierras near Mata Ortíz to learn how to look for manganese, the base ingredient for the black paint. Leonel didn’t make pottery at the time. However, his wife Elena was making monos, ceramic figures in the style of her brother, Manuel Rodriguez, and Leonel wanted to learn how to make his own paint, instead of borrowing from his brother-in-law.

Elena worked on the figures of “Moctezumas,” the local name for the Pre-Columbian inhabitants, while her husband tended his land and helped his father with his fields. When the drought hit Mata Ortíz in 1992, Leonel found he didn’t have a lot of work to do in his fields, so he began to help Elena. First, he sanded and polished, then graduated to “rellenarlas,” filling in the designs she outlined on her pottery.

“The sequia (drought) was good and bad for us,” Leonel said and Elena agreed. Many became potters at this time, learning from their neighbors and relatives who had earlier taken up the craft. At first, he made his own pottery, but by the middle of 1993 Leonel was buying jars from others to paint, and he began signing his work. Early designs were limited to basic cuadritos, patterns of tiny squares covering the clay surface, and other simple formats.

It was only in April of 1995 that Leonel began incising his designs in the method they call calcado in Mata Ortíz. His inspiration came from another brother-in-law, Oscar Rodriguez, who dabbles in this style. However, Leonel Lopez directed the sgraffitto art to a new level. Again, his first works were simple. He would slip the pot red or black, then incise fish, flying swans or other animals.

The tools for his work are also simple. “I started with just a jacknife, but then a trader gave me a dentist’s pick.” He still uses the knife, but has also purchased two other dental picks.

His big breakthrough came after his invitation to an important weekend demonstration at the Arizona-Sonoran Desert Museum in Tucson the same year. “A collector asked me to make a special pot,” Leonel said. “He wanted one that showed a day in the Sierra, with all kinds of things from nature.” The red and white pot that emerged portrayed splendid stags, fawns frolicking among the trees and swans flying overhead.

“The collector never bought it,” Leonel remembered. “But someone else did and thanks to the collector, I got a great idea.” Now, he alternates between sets of animals which repeat all over a pot and the “story ollas.”

Pottery success has been good for both Leonel and Elena, who live in a six-room house with their two sons, one 13, the other a toddler.

“Before we made pottery,” Elena said, we had only two rooms. Now, we have three bedrooms, a salon, kitchen and bathroom.” Last year, Leonel slapped down enough cash to buy a new bright red Dodge Ram truck with all the trimmings.

Although he is now a full-time artist, he still finds time to tend cattle and help with brandings and roundups. In Mata Ortíz, most of the potters are “ambidextrous.” When they aren’t turning out ceramics, the men are farming or ranching; when the women aren’t up to their elbows in clay, they are cooking, cleaning and taking care of their families.

The Lopez family looks to the future with hope that the pottery industry will continue. A drive for most potters is to provide a better life for their children.

Things must be going well, their older son spent his spring vacation in Acapulco!