Juan Mata Ortíz is a small village of potters, farmers and cowboys in Northern Chihuahua. About 30 years ago, an unschooled artistic genius, Juan Quezada, taught himself how to make earthenware jars in a method used hundreds of years ago by the prehistoric inhabitants. Now, his works are known worldwide and over 300 men, women and children in the village of less than 2000 make decorative wares. Much of the polychrome and blackware is feather light and exquisitely painted.

Many of the potters are also cowboys and farmers. These stories serve to document the art and the people in this unassuming pueblo, which is often called “magical” by the relative handful of tourists who visit. Enjoy this other view of Mexico.

Some people move through their lives with a style and elegance that defies explanation. It is not something that is learned; it is just there, an aura that envelops them. It is the charisma that causes us to turn our heads when they enter a room, or to glow in pleasure when we walk into their kitchen in the morning for coffee . . .

Some people move through their lives with a style and elegance that defies explanation. It is not something that is learned; it is just there, an aura that envelops them. It is the charisma that causes us to turn our heads when they enter a room, or to glow in pleasure when we walk into their kitchen in the morning for coffee . . .

We were looking for pottery. Two black ceramic pots on the windowsill of a small adobe home along the street by the river prompted me to stop. The door opened and a slender woman with long gray hair hanging below her shoulders came out to greet us. Smiling at us from a face the color of tanned leather, she introduced herself as Consolación Quezada and motioned for us to enter. I was struck by the way she carried herself with such regal contentment, as though she knew who she was and knew it was good.

We passed through the doorway into a small bedroom where an array of pottery was displayed on a double bed-a study in styles and colors. There were black-on-red jars, a variety of red and black-on-buff polychrome, corrugated pieces and a delightful swimming-frog jar.

“My son, Hilario, made this one,” Consolación said, pointing to a polychrome. “My other son, Mauro, made this one. That one, my brother, Reynaldo,” pointing to the frog.

“And you?” I asked. “Which is yours?” Smiling proudly, she pointed to a large black-on-red olla. “Your whole family makes pottery?”

“Sí.” Again that contented smile. “Everyone.”

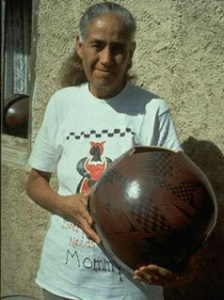

That was my first impression of Consolación Quezada, recorded in my field notes in August 1989 on my second trip to Mata Ortíz. She is the older sister of the master potter, Juan. He taught her to make the unique earthenware about 25 years ago. Living in a dusty little village with little opportunity, especially for women, she quickly realized the economic importance of potterymaking to her family. Now, her daughter and four sons all support their families with pottery sales.

On that first day in her home we connected immediately as friends, Consolación and I. On subsequent trips to the village she insisted I stay at her and husband Lupe’s house. The bedroom with the supermarket of wonderful pottery became my second home for several years of long weekends and vacations, until I constructed digs of my own. Each morning I would wake up at about 5:30 to the pit-pat-pit-pat of fresh tortillas being made in the kitchen on the other side of a flimsy curtain laundry-pinned closed to give me some privacy. Soon her brother, Nicolás – a potter almost as brilliant as Juan – would arrive for coffee. Usually he had been up since 4 a.m. painting greenware. I would pull myself out of bed, stretch myself awake and join them.

On that first day in her home we connected immediately as friends, Consolación and I. On subsequent trips to the village she insisted I stay at her and husband Lupe’s house. The bedroom with the supermarket of wonderful pottery became my second home for several years of long weekends and vacations, until I constructed digs of my own. Each morning I would wake up at about 5:30 to the pit-pat-pit-pat of fresh tortillas being made in the kitchen on the other side of a flimsy curtain laundry-pinned closed to give me some privacy. Soon her brother, Nicolás – a potter almost as brilliant as Juan – would arrive for coffee. Usually he had been up since 4 a.m. painting greenware. I would pull myself out of bed, stretch myself awake and join them.

Nicolás now lives in Casas Grandes, about 20 miles away, but the coffee ritual still continues with Consolación and myself – albeit at a slightly later hour. Many stories have been told around that little kitchen table.

When she was a little child, her parents moved the family from the village of Namiquipa in central Chihuahua to Mata Ortíz. Father Don José obtained land and cattle and they all settled into a new life near the river. When she was 15, Consolación fell in love with a local boy and a wedding was planned. Curiously, her parents decided to sell their land, all their cattle and move back to their old home. The wedding would be held in Namiquipa and the young couple would live there.

Unfortunately, as Consolación tells it, no one conferred with the two novios. “The night before we were all to leave, we eloped.” She smiled. “We ended up staying in Mata and my parents didn’t move. They bought another house and cattle and stayed, too.”

Her brother Juan was just a little boy at the time. If Consolación hadn’t eloped and everyone moved back to Namiquipa, would he have become a world famous potter, I wondered.

“Oh, yes,” she replied. “He would have made pottery in Namiquipa.” But, I thought, so much of his influence came from the ancient shards he found in the hills near Mata Ortíz. And, the other town does not have the easy access to US markets that Mata does. Curious how life skips and dances along the twists and turns of Destiny’s road.

Consolación’s early years of marriage were hard. This young girl moved away from her family for the first time and into the mountains with her husband as he struggled to find work in sawmills. “He abused me badly,” she told me one day. “I finally left and returned to Mata and we divorced.” By then, she had two sons and a daughter, Dora. Back home, she eventually married Guadalupe Corona and two more sons, Hilario and Mauro, were born.

“We had nothing,” she said. It was a poor, humble life before the Quezadas began making pottery. In the whole village there were only three outhouses. Consolación had one. Other families in the town . . . well, you get the idea.

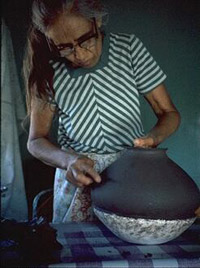

The first item she bought with money saved from pottery-making was a propane gas stove, which she still uses to boil the water for her coffee and to do most of her cooking. Her house has expanded now to four rooms – one of which is her bedroom/studio. It is there that she made a pot a day for many years. She is particularly well known for her unique red-slipped 13″ high jars. The red paint came from soft stones found in the state of Sinaloa by her son-in-law. Now, that source has “dried up” and she contents herself with making large blackware. Even in her late 60’s she makes two or three a week, when her health permits.

The first item she bought with money saved from pottery-making was a propane gas stove, which she still uses to boil the water for her coffee and to do most of her cooking. Her house has expanded now to four rooms – one of which is her bedroom/studio. It is there that she made a pot a day for many years. She is particularly well known for her unique red-slipped 13″ high jars. The red paint came from soft stones found in the state of Sinaloa by her son-in-law. Now, that source has “dried up” and she contents herself with making large blackware. Even in her late 60’s she makes two or three a week, when her health permits.

“My hands tell me to stop (she often suffers from arthritic pain), but my heart won’t let me,” she smiles as she builds another large olla.

While her body may ache, she has never lost her sense of humor. Once she told me about a pot made in the early years. “After making the large bowl, I put it out into the sun to dry, then got ready to go into town. I told Dora, who was 12 then, to keep an eye on it and bring it inside if it started to rain. Well, she took a nap and it did rain. She woke up and brought it in but it was badly pock-marked from the drops.”

Consolación laughed and smiled shyly. “We fired it anyway and it didn’t break. The next day we sold it to an American lady, telling her it was an ancient ware.”

In those days there were very few potters and they didn’t sign their pieces. A tourist coming to the village was an unexpected surprise. Now, except for the summer months, there are tourists almost daily, more than 300 potters and the earthenware is all signed. Consolación has a beautiful new indoor bathroom and watches her novellas on a 26-inch color television. The broadcasts are caught on a monster satellite dish that sits in her yard-courtesy of her youngest son, Mauro, whose pottery commands prices between $300 and $1000.

Our coffee klatches aren’t always private. She happily greets my guests, never bothered that four or five strangers may arrive at 8 a.m. She’s already in the kitchen and the water is boiling. For many of these gringos, that half-hour is the highlight of their visit to Mata Ortíz. Her sons or daughter may drop by, as well, sometimes to chat for awhile, sometimes just to say hello and be sure she is OK. We always find something to talk about, and it often revolves around her family, her children. “I have had a hard life, but I have wonderful children,” she says.

Consolación has left us with three legacies – her pottery, her children and her grace. We should all be so lucky as to meet someone like Consolación Quezada during our lives. We can learn so much about how to make do with what we are given, how to take advantage of opportunities presented to us and how to live elegant lives.