“Without watercolors we wouldn´t know nearly what we know about the ancient Mexicans,” said the gentleman across the expanse of polished desk with a sweet smile.

“All of the codexes were painted with colored pigment in water on amate paper (thick, handmade paper from the inner bark of the amate tree that only grows in the State of Morelos). Cortés and the priests burned a lot of those ancient documents, but hundreds of them remain. A few are in museums. Many others are in the hands of the elders of small villages here in Mexico, and they are preserved like holy writ, because they contain all the teachings, all the beliefs of the ancestors.”

I felt my reporter´s pulse quicken. I know that sounds corny, but I wanted to know why this man had devoted his whole life to such a seemingly frivolous activity as painting with water and thin color on toothy paper, and I knew at once that this was at least part of the answer.

Alfredo Guati Rojo was born in Cuernavaca on December 1, 1918. He had what he calls “an artistic inclination” from the time he was seven. Perhaps, he thinks, seeing the murals of Diego Rivera on the walls of Cort´s’s palace made him want to be an artist. Happily he came under the tutelage of a primary school art teacher who also happened to be a student of San Carlos Academy´s famous maestro Eduardo Solares.

Solares came to Cuernavaca to paint a new fresco on the walls of the Palacio de Cortés. The young Guati Rojo helped lay out the tareas, areas that could be painted in one day´s work. Fresco painting is really a type of watercolor, using a prepared white wall instead of paper. Watching Maestro Solares work whetted the young man´s appetite for more.

Guati Rojo´s father, a practical man, wanted his son to study law, but he didn´t stand in the way when he discovered that Alfredo wanted to study art instead. Alfredo Guati Rojo received his Master’s degree in plastic arts from the San Carlos Academy in 1940. His education encompassed all of the arts but he “always tended towards watercolor.”

“Water, for me, has always had its mystery. Watercolors do what they want to do. You can´t change them for anything,” the gentleman tells me.

“No one can really say they have dominated the technique. Every time I start a new painting I am terrified that I will fail.”

I had stared at the beautiful face of a woman in one of his watercolors on the wall in the anteroom to his office before he arrived. It was rich and alive. I couldn´t imagine someone who could create such a work might have started it out with trepidation. The colors were so sure, the shape of the face, the eyes, the lips, all so exquisitely formed they might have been a tinted photograph. Or were my eyes reading more into the picture than he put into it with his watery brush?

When Guati Rojo left San Carlos Academy, after working for a while as his teacher ´s assistant, he had to face every artist´s dilemma.

“It always the problem for people who graduate from art school – what do you do to make money? When you are unknown, as I was at the time, no one wants to buy your work.”

He decided to teach young people art in short courses. In those days art school was a many-years-long commitment, and some young people didn´t have that much time or money to spend. In 1954 an art institute was born that offered courses of three year’s duration in ceramics, fashion design, furniture design, and jewelry making, as well as in the plastic arts. In 1957 the institute rented a large house in Colonia Roma here in the Capital, where watercolors began to be shown as serious art in an actual museum setting. Thus was born the ” Salon Anual de Acuarela,” which continues to this day. The Salon is now in its forty-second year and going strong.

“Before we began to show watercolors in Roma, I had gone to a friend of mine who was a gallery owner to ask if I could mount a show. The gallery owner declined. Watercolor was only a minor art, she told me. A step-sister to the real art–oil painting.”

I told Guati Rojo I didn´t understand why.

“Well,” he explained, “the technique was popular until the 19th Century, in fact; but when lithographic portraits and landscapes became available, people lost interest in watercolors. Also, people were used to seeing the large paintings of the Renaissance and the Impressionists and thought that was the only art there was. Watercolors tended to be small and their colors were thought of as thin, almost transparent, insignificant.”

“But the light that shows through from the white paper is what makes them beautiful,” I protested.

“After we started to show more watercolors, people began to get interested. The reviews of our shows were nearly always favorable. And watercolorists were beginning to sell their art again.”

Guati Rojo and his wife, Berta Pietrasanta, had spent the years since he graduated from San Carlos collecting watercolors – of his maestros and fellow students while he was connected to San Carlos, and later from his own students, some of whom have become quite successful watercolorists.

In 1977 they created the National Watercolor Museum and approached the Secretary of Education with an offer to donate their own collection to the State if the secretariat would help them fund the museum. The Secretary was interested, but never came through. So the Guati Rojos formed the Amigos del Museo de Acuarela in hopes of running the museum even without government help. For two years they raised money by presenting shows and concerts.

The museum was beginning to work when disaster struck. In 1985 Mexico City was devastated by a huge earthquake. The building the museum occupied in Roma was destroyed. In a way, however, its ruin was a blessing.

” I guess the city government felt sorry for us,” Guati Rojo grins. “They finally agreed to buy us this house we are sitting in now. It was tremendously expensive with a large lot, and the government told us that after this they could do no more.”

But it was enough, and the Museo Nacional de Acuarela made itself at home in Coyoacán.

“At first the Amigos paid annual dues of just 50 pesos. Now they pay around 200, but it is not nearly enough to run this museum, although we do appreciate their moral support. We need more members and friends with generous pockets.”

I wondered how the museum could afford to even pay its electric bills at that rate.

“How can you send watercolors out all over the world as you do for shows?” I asked.

“Well, simple, we take the paintings out of the frames before we send them. That way we can send out a whole show in one box. The galleries who exhibit them overseas have to agree to frame the paintings themselves and then, when the show is over, remove them and send them back to us. In fact, the Secretary of Exterior Relations has helped us by paying for the shipment of paintings. It is a cultural exchange, after all. Of course, we pay for the insurance both ways.”

These shows of Mexican watercolors have brought the Museo Nacional de Acuarela international renown. The museum is the first of its kind in the world, and watercolor painting has become accepted all over the world, partly due to the Guati Rojos and their work as curators.

Alfredo Guati Rojo´s own watercolors have contributed in no small measure to the success of the Museo Nacional de Acuarela. He tells me with genuine amazement that nowadays all he has to do is let his “fans” know he is about to start a painting, and someone buys the piece sight unseen. That is how the Guati Rojos have managed to support their expensive “hobby.” Also, the maestro teaches two watercolor classes a week in the museum.

“But I am a very old man, and who knows how much longer I will be able to support this place with my work. I am not going to live forever,” he smiles again–not a wistful smile, but the smile of a man who is satisfied he has done an exemplary job.

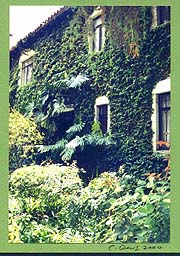

Over the last fourteen years, the Guati Rojos have renovated the large house in Coyoacán and turned it into a showplace. The lovely garden that surrounds the house has been created, little by little, out of the creative minds of the two. It is a work of art in itself, with manicured expanses of green lawn, brightly flowering shrubs, house-covering vines, trees, flagstone walks, white iron benches, old-fashioned street lamps, a weather vane, and several colorful modern sculptures in the ancient Mexican tradition.

There is an “espacio poético,” a poetry garden, with a large stone sculpture that signifies water and a stele honoring the Aztec poet Nezahualcoyotl. Some of the ancient poet´s work is translated into Spanish on several marble slabs mounted on the wall of the house. Guati Rojo´s own poetry also graces the garden.

“I love poetry almost as much as I love watercolor painting,” he tells me. As a sometimes poet myself, this intrigues me even more. But I want to get him back on the subject of watercolors and history.

“You know, the British like to think they invented this art form in the 18th Century, but they didn´t. Even the cave paintings at Altamira in Spain are a kind of watercolor. They used colored clays or other natural pigments mixed with water to paint all those wonderful animals on cave walls, and those watercolorists painted some fifteen thousand years before JMW Turner and Constable. The ancient Egyptians also used watercolors to decorate their temples.

“These early forms of watercolor (called tempura and fresco) only needed the Chinese invention of paper, which was transmitted by the Arabs into Spain and from there into Europe, to make them into the modern art form we call watercolor or aquarelle.

“Watercolor became a sort of non-phonetic language in the able hands of the early Mexicans. Until the 18th Century they even used watercolor to paint pictures of their complaints on amate paper and submit them to the Spanish oidor, or judge, for his consideration. Since they were illiterate people, they had no other way to communicate “officially” with their European overlords. The Mexicans used these painted “codexes” also to delineate the boundaries of their villages and lands. They are zealously guarded even now. “These early watercolor paintings are a national treasure.”

The collection of watercolors at the Museo Nacional de Acuarela in Coyoacán is also a national treasure. On its walls you can see such masterworks as Pastor Velazquez ´s warmly handsome “Mujer indígena,” Manuel M. Ituarte´s flashy “Amapolas” and his small landscape masterpiece “Bahia de la Habana, Cuba.” There are also works by Eduardo Solares (1888-1941), Leandro Izaguirre (1857-1937), as well as several striking pieces by Maestro Guati Rojo himself.

There are tiny watercolor portraits in lockets, book frontispieces, architectural drawings, and fragments of Aztec codices, in addition to the larger and more modern works.

I am thinking that the elegant gentleman I am sitting across from is just as much a national treasure as the paintings he has collected, although his sincere modesty would never permit him to agree.

When I ask him to sum up his experience as a watercolorist and a museum curator, Alfredo Guati Rojo tells me in no uncertain terms, “I have been given so much by Mexico; this is the least I can do to give something back.”

To get to the Museo Nacional de Acuarela, take the light-green line Metro to Miguel Angel de Quevedo. Walk east on MA Quevedo two blocks and take a left on Salvador Novo. The museum is at number 88, on your right about a block up. Call 55-54-1801 for more information. It is open Tuesdays through Sundays from 11 a.m. till 6 p.m. Entrance is always free for everyone.

Are there any sites showing his work?

Google image search throws up the following: https://www.google.com/search?q=%22Alfredo+Guati+Rojo%22