We rented our first house in San Miguel on a Wednesday. The street, Indio Triste, was like many in San Miguel–cobbled, narrow, and the walls that surround the houses and gardens are built right up to the narrow stone sidewalks. It was a pretty house, with a shady garden, and the barrio was uncommonly quiet.

The next Tuesday, however, when we opened the inside shutter to our one barred window that looked out on Indio Triste and pulled back the curtains, we discovered we were an integral part of the back wall display case of a small electrical appliances department.

Sad Indian street had been magically transformed into a jolly tianguis, which is an ancient name for a street market that moves to different neighborhoods and villages on different days of the week. The tianguis, we discovered, filled two blocks of our street and at least ten more blocks in the immediate vicinity.

Every Tuesday for the next month, we left and entered our house past Aiwa and Sony and Panasonic boom boxes and teevee sets and Walkmen and musical alarm clocks.

” Buenos días,” said the cheerful vendors as we squoze out our garden gate and through their jam-packed shelves of gleaming merchandise.

“How do you manage to sell these things so cheap?” I asked once.

“Oh, Señor, we have our ways.”

The next shop down sold cotton towels. We bought quite a few of over the weeks to stock up our several bathrooms. A few steps beyond the linens were vegetables, fruit, an ample toy department, competing plastic bucket and broom emporiums, and plucked chickens by the naked, yellow flock.

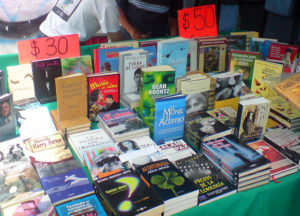

A block down, the red meat stores proudly displayed entire cows’ legs and various other animal parts, shiny viscera, and sometimes even the head of a forlorn looking goat garlanded with garlic. All this wild profusion of metal-frame stands with bright plastic awnings–the puestos–packed with merchandise from all over the world sprang up overnight like gaudy bamboo shoots. The streets filled with shoppers from around 8 a.m. and stayed busy till sundown, when the merchants began to dismantle their stores-for-a-day and discuss their earnings-or lack thereof.

The tianguis was soon closed down by the city hall bureaucrats and their henchmen, gun-toting kid cops, at the vehement behest of our more upscale neighbors who wanted to use the streets for their cars.

We were awfully disappointed.

Imagine our joy upon moving to México, DF, to find, a block down from our aerie (we like to call it a penthouse) apartment in Coyoacán, a tianguis that easily rivals the one in San Miguel. And that´s just on Saturdays. On Tuesdays an even bigger market pops up on the street behind us. Two days a week of the best shopping in the world.

We always try to go to the tianguis hungry. Every vendor in whose produce we show the slightest interest offers, no, insists upon, a taste. When I buy queso fresco, which here in the City is called queso panela (I had to admit to being from la provincia when I didn´t know the correct name for this commonest of cheeses), the charming middle-aged couple running the puesto always feed me slices of every queso they have.

At first just delicate wedges, and then on tortilla chips, and finally on a delectable green jelly-looking stuff they tell me is a dulce made from apples. One time they even showed me how to combine a thick string of queso oaxaqueño and a thin pink slice of sweet ham inside a flour tortilla to make a light lunch.

“That´s what we have during the afternoon here when we get a little hungry,” said the grinning owner.

Now that´s the way to buy cheese.

Every fruit vendor in the tianguis worth her or his salt unfailingly offers a slice of apple, a wedge of watermelon, orange, tangerine, or grapefruit sections, to say nothing of mamey, banana, and pitahaya pieces (don´t you know what a pitahaya is?) and other gorgeous tropical delicacies that I don´t have a clue what their names are and can never get them straight, no matter how many times I ask.

Recently I watched a dapper gentleman in a white shirt and tie at my favorite fruit puesto fingering papayas ever so gently and selecting several for the next few meals at his home. I always just trust the vendor to give me the ripest one he has.

“How can you tell which ones are ready to eat?” I asked him.

“Well, you can tell when they feel a bit flojo.”

“Flojo?”

“Yeah, take this one, for example.” He handed me a fat, greenish papaya. The flesh under its cool skin felt just a little squishy.

“That one´s ready to eat right this minute.”

“What about this one?”

“Tomorrow morning for breakfast.”

Over the next fifteen minutes the gentleman showed me six other papayas, some quite green, some golden yellow swatched with light orange, all in different stages of ripeness. He told me the color isn´t nearly as important as the degree of squishiness under the skin. And now it was time for my test.

“Okay, when would you eat this one?”

“Around four tomorrow afternoon?” I ventured.

“Now you´ve got it,” he laughed and patted my shoulder proudly.

David and I both love all the puestos in the tianguis, especially ones where people are sitting and chatting and nibbling on tacos or crispy pork skins drenched in salsa cruda. But our favorite, by far, is the tortillería.

We like to watch the young tortillera pull off a piece of dough from the blue mass under a checkered plastic tablecloth and put it between flimsy plastic sheets into her silvery press where she flattens it out in an instant. She carefully strips the blue dough from the plastic and then puts the thin round onto her large metal comal where it toasts a bit, fluffs up like a balloon, and sends out fragrant signals that it´s time to flip. She turns the tortillas with deft fingers that seem oblivious to the comal´s heat. Once they are done to her satisfaction, she stacks them into steamy blue piles under an embroidered cloth. Two dozen cost fourteen pesos, which is a little pricey for tortillas, but worth every peso and more once you get one of these delicate beauties between your teeth.

David´s idea of heaven is the gumdrop puesto. Gumdrops are his medicine of choice when his Parkinson´s drugs give him a scratchy throat. The little morsels come in tasty colors and have a fine sugar coating. There are different sizes and textures, too. Some are shaped like orange sections; some like buttons. Some are of almost the same consistency as jello, and some are chewy as bubblegum. And there are hundreds of different kinds of candies along with the gumdrops. The señora periodically swats away the bees who´ve come to sample her wares without paying. She doesn´t even bother to ask David for his prescription.

I am fascinated by the molé stands. I call them molé stands, but they usually also sell chiles – of every size, shape, and variety – and some are already ground and mixed with other spices. One is chile pequín, that lovely little red devil of a chile, mixed with lime and salt, and it is used to sprinkle on jícama and on some of the blander fruits. Another red and powdered variety my vendor tells me should only be used, sparingly, in, not on, other foods. The chileistas invariably warn the gringo shopper about the dangers of particular chiles, believing that hot is taboo to our “refined” palates. Of course, David and I are from Texas where men are men, and chiles are chiles and…, oh, whatever that silly saying is.

Moléistas are the alchemists of the tianguis, and they are proud of their Great Work, sometimes to the extent they do not deign to bother to explain to the molé neophyte the inner workings of the magic. After wasting a lot of my time cultivating the molé people in Coyoacán´s inside market to no avail, I finally have found a friendly family of these rare creatures who will divulge secrets, sort of. My guys are only at the Saturday tianguis, and I am keeping their exact whereabouts a secret (unless you email for more information).

The secret of the molé called pipián, for example, is that it contains the ground seeds of one of the red chiles – you know, those little potent pips the cookbooks all tell you to throw out immediately without touching them. Molé pipián is a golden orange color and goes best with chicken, turkey, pork, and vegetables. My favorite Mexican cookbook, Rick Bayless´s Mexican Kitchen , offers a recipe for “roasted Mexican vegetables in green sesame pipián,” that sounds fabulous, although Rick apparently is not able to buy the molé powdered like we are, and he goes into incredible detail on how to prepare the molé itself.

At most molé stands you can buy the molé either dried and ground or shiny, dark, and viscous. The difference, according to my sources, is that the dried lasts longer – up to a year – while the moist version will go bad in a week. To use the dried and powdered molés all you have to do is mix them with chicken broth (or whatever stock you like best; vegetable, for example).

My favorite molé alchemists at the Saturday tianguis make a deep red, almost black molé they call molé almendrado, which contains, among many other things, almonds (hence the name), ancho chiles, pasilla chiles, and pecans, all ground and mixed with chicken broth. The flavor is complex and intriguing (sounds almost like fine wine, eh?).

And to show you why I call these special people alchemists, their molé verde, a simple little name, is made from chile serrano, cilantro, lettuce, peanuts, sesame seeds, clove, cumin, garlic, onion, and English pepper, all in intricate relational amounts, and that´s just the part they will tell me about. Don´t let the simple little name fool you, this molé is a classic, complicated and rich and beguiling. And the whole is much greater than the mere sum of the parts.

Rick Bayless is even wordier than I am when he describes the Great Work these artists create out of base elements. He says that a particular good red molé “offers the silken fullness of a 20-piece dance band, the intricacy of a Persian rug, and the intensity of a Siqueiros mural.” Now, doesn´t that just whet your appetite?

No tale of the tianguis would be complete without a word or two about huauzoncles. I know you´ve seen them, if not alongside a country lane in central Mexico, at least in the green puestos in the tianguis. Huauzoncles, or guauzoncles as the word is spelled by Diana Kennedy in her wonderful cookbook The Cuisines of Mexico, are Chenopodium nuttalliae. They look like tall weeds with small green seeds in a thicket at the top of the plant.

In the Saturday tianguis in Barrio San Lucas, Coyoacán, you can buy huauzoncles already breaded and stuffed with queso panela and browned. They look a little like, well, maybe smoked fish. The same people who sell already cooked and stuffed poblano chiles and jalapeños sell huauzoncles, as a rule. The first time I bought some I refrigerated them and, for a day or so, pondered over just how I would prepare and serve them.

Turns out, it is so easy a kid could do it. I stuck them in the oven preheated to 240 degrees centigrade for fifteen minutes on a nonstick cookie sheet. They began to sizzle and fill the house with a delightful aroma after just a few minutes. Twenty minutes, in fact, would probably have melted the cheese a bit better, but the tantalizing smell just kept saying, “Serve me!”

So I did. On a bed of plain white rice topped with the rico sauce the lady at the puesto gave me, a dark and edgy blend of, I think, chile ancho and jitomate and, heck, who knows what else. We sat down in front of these savory piles and realized we had no idea whatsoever how to eat the danged things. I tried cutting mine, but the really tough inner stalks don´t lend themselves to table-knife cutlery. They might respond to a buzzsaw.

David came up with the idea of pulling the bunches of huauzoncles stems apart and running them through his teeth to clean off the soft seeds, green leaves, and that divine light-brown breading. That seemed to us to be the only solution, but we felt like ruminants.

“Hmmm,” said David, a somewhat picky eater, “These are delicious!”

We ended up with a tablecloth full of stems, beards full of little seeds, and plaque-free teeth. Reminded me just a little of my youthfully indiscrete days when things got down to “seeds and stems.” But, oh what seeds and stems are these huauzoncles. If you haven´t tried them, you must. The tianguis is the only place I have seen them already cooked, and, believe me when I tell you, it´s too darned hard to bread and cook the things yourself.

Since our virgin run as huauzoncle munchers we have discovered that the tianguistas also, on occasion, strip the leaves off the stems and form them into delicate tortitas, or cakelets, stuffed with the same queso panela and encrusted in the usual light breading. That is the way to go, let me tell you. I have found that if I let them know a week ahead of time, the vendors will make me a pile of tortitas de huauzoncle – you know, for our comida guests who are first-timers (or don´t have sturdy teeth).

The tianguis is akin, maybe, to the Arab souk, but with a distinctly Mexican soul. It is certainly an ancient tradition, stretching back beyond Aztec times and probably back to near the dawn of our mercantile species. The tianguis requires a certain set of politenesses and other important rituals of doing business. It is never rushed. A simple, “No, gracias” or “Ya tengo” or “La próxima vez” and a pleasant smile will do when someone profers something you don´t want.

There is no bargaining; if you don´t like a price, go to another puesto, although I have never seen sellers vary much in their prices from puesto to puesto. Quality, however, does vary. Some of these sellers just have a knack for buying the freshest, tastiest, and most appealing produce. This is especially true when it comes to greens, an important part of the Mexican cuisine. A tianguis needs to be studied, calmly, intently, and thoroughly. And when you find a great puesto, stick with it. Its owner will be giving you obsequios — handfuls of fresh cilantro or juicy oranges or extra bits of cheese — before you know it.

Most of our neighbors send their help to shop the tianguis. I guess it saves time. Even if David and I had “help,” we wouldn´t dream of foregoing the pleasure. Our former neighbor, Molly, who is as aristocratic (in the best sense of that word) as they come, shops the tianguis herself always. I have caught her walking about with a steaming blue tortilla in one elegant hand and a bolsa full of fresh verdolagas in the other.

“I love the tianguis,” she tells me. “It makes me feel like I am back in time.”

Our latest move has brought us to another part of the city, the bustling and scruffily chic barrio named San Rafael in Colonia Cuauhtémoc. We are about a half block from Parque Sullivan, that manicured collection of azaleas and jacaranda and palm trees that becomes a wonderful art fair on Sundays, and, well, we must have the proverbial “luck-o´-the-Irish.” The western-most strip of the park that is partly a parking lot for the Cuauhtémoc delegation offices during the week becomes, you guessed it, a rollicking, pink-plastic-shaded tianguis that is the best we have seen yet.