A most unusual museum crowns the top of Trozado Hill in Guanajuato, Mexico. Its collection of objects – mummified human corpses – serves to provide funds for social assistance in the city, and as a powerful memento mori.

The most famous tourist attraction of this part of the country, the museum is located above the municipal cemetery of Santa Paula. Visitors enter along a row of shops selling all types of tourist trinkets; wandering vendors smilingly offer candy mummies. Ghoulishly, children munch these sugary “recuerdos” (souvenirs) as they wait for admittance. A halloween atmosphere with a delicious anticipation of fright prevails. Long lines of tourists queue up for the visit.

Inside, a guide begins an interesting spiel in Spanish as the group passes by the glass cases containing 118 mummies whose bodies were exhumed between the years of 1865 and 1979.

“Here you see the smallest mummy in the world,” the guide says, as he points to the tiniest of the museum’s inhabitants. “This lady was found sitting with her newborn child; this medical doctor is the first of the mummies. Not all the mummies have come from our cemetery; some have been brought from Celaya.”

As round-eyed children and anxious adults follow him, gazing face to face with these powerful reminders of life and death, the guide continues telling the traditions and legends of Guanajuato through the stories of the mummies. These frame a fantastic world in our imagination. He tells of the virtuous baker’s wife found hanging. Her brutish husband, arrested and executed for the crime, protested his innocence to the end. No one knows the truth; the only marks on the body were those of the rope. The story of the unfaithful woman buried alive fascinates everyone. The most recently discovered mummy is half mummy, half bones. The faces of some of the adult tourists begin to pale. They seem grateful to spy the free restrooms near the exit.

With the exception of one who appears to be laughing, most of the mummies have their mouths open as if they were screaming. The guide carefully explains that this is caused from a natural muscle movement during the process of rigor in an unembalmed body. The observers give credence to his silent words. The mummies seem to have a black scream frozen in their mouths, telling of the obscurity of death and recording their trip among the fleshless ones.

Several times, through signs and the words of the guide, visitors are reminded that the mummies are working hard for the children of Guanajuato. All the proceeds from admissions and from the sale of postcards, t-shirts, and booklets in the museum gift shop, go to the city’s poor children through the medium of municipal social works. Somehow, this makes things seem better, less gruesome. After all, these mummies are just doing a job.

In their glass enclosures, most of the mummies recline with a soft pillow under their heads. Some are sitting or standing, and others bear signs that speak a philosophical message. One corpse is shown in its coffin. The thought- provoking inscription reads: “This is how you see my life; this is how I see the truth.”

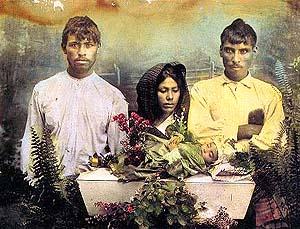

Wall displays between the glass cases call forth contemplation and amusement. One set of photographs vividly displays “Los Angelitos” (the Little Angels.) When a young child dies in Mexico, there are certain rituals connected with his death and burial. Many people believe that the souls of these innocent little ones immediately join the angels in Heaven. The child is dressed as a little angel or saint, crowned with a crown of flowers and laid on a beautifully decorated bier. A painting or photograph is then made which the family keeps on its home altar in remembrance of its own little “angelito.”

Next to this display is a case of some of the smallest of the mummies. One is dressed as Saint Martin de Porras. Another wears a well-preserved crown of flowers.

Another wall causes visitors to laugh, breaking the horrible tension that has been building. The calaveras of the famous artist Guadalupe Posada evoke humor. A second look calls forth contemplation from some observers. Posada’s lithographs are now famous world-wide. His laughing, dancing skeletons are among his most famous works of art. The calaveras are engravings showing smiling skeletons wearing clothing and cavorting about in all manner of poses. Each is completed with a funny, usually sarcastic poem. Deep thoughts are often hidden in the humor of the words. During the festivities of Dia de Muertos (all soul’s day), the people exchange these calaveras much as Americans exchange Valentines in February.

The municipal cemetery of Santa Paula was built in 1853 when the previous cemetery was filled. In 1865, the new cemetery was extended. The body of Remigio Leroy, a French- born doctor, was exhumed. To the surprise of the cemetery workers, the body was found to be naturally mummified.

Because of the enormous number of burials, the cemetery followed the old European custom of exhuming and cremating bodies after five years. Fees could be paid to insure that a family member stayed buried, but most people did not, or could not, afford to pay them. During subsequent exhumations, a number of mummified corpses were found, and these began to be exhibited as a tourist attraction after the year 1870.

Mummies, of course, have existed since long before the Christian era. The Egyptian mummies were carefully embalmed in order to preserve the bodies for a future life. The exact causes for natural mummification such as those of Guanajuato have never been completely explained by science. Natural mummies have been found in many parts of the world. Some mummies which were not embalmed have been found in the hot, dry desert of Egypt; the cold dry climate in other parts of the world has its share of these scientific oddities.

Excavations near Bordeaux, France turned up hideous mummies which were displayed in several places toward the end of the Middle Ages. Science has never successfully answered the question, “Why do some bodies remain incorrupt when others rapidly disintegrate in the natural process of putrefaction?”

Scientists acknowledge that most natural mummification is produced in the absence of water and in the presence of soil that is salty, or rich in nitrates and aluminum. These conditions are present in parts of the cemeteries of Celaya and Guanajuato where the majority of the museum’s denizens were found. The rapid dehydration makes the bodies less susceptible to microorganisms and insect larvae. The anatomical external parts are usually preserved while the interiors often dissolve. Natural mummies are fragile and break with only the slightest pressure.

Memento mori – remember, man, that you are going to die. The medieval Christian became fascinated with the physical properties of death and forgot to contemplate the happy Christian message of the Resurrection. The medieval outlook on the vanity of earthly things exerted great influence on the world’s literature and art.

The mummies of Guanajuato speak to today’s Christian in a powerful voice – a compelling memento mori. They scream forth, too, a plea for our remembrance of our faithful departed.

“Remember also, O Lord, your servants who have gone before us with the sign of faith, and rest in the sleep of peace. To them, O Lord, and to all who rest in Christ, we entreat you to grant a place of comfort, of light, and peace.”

[Roman Canon, Eucharistic Prayer I]

Oddly, these silent orators also speak of life. Life is affirmed through death; death is not the negation of life but rather its affirmation. The mummies of Guanajuato speak to the Christian of the joyful affirmation of the very heart of our religion – life everlasting. The pain of death is combined with our joy at the hope of life everlasting. Our loved ones do not die; they live again in God. It is through the crucifixion that we see the bountiful promise of the resurrection. Because He lives, we too shall live.