Good Reading

Throughout the novel, we see the forceful character of Frida displaying itself

Throughout the novel, we see the forceful character of Frida displaying itself

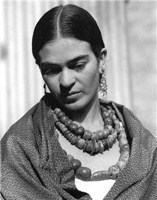

The largest Frida Kahlo exhibit ever has just ended in Mexico City. Timed to coincide with the 100th anniversary of her birth, the show featured 65 oil paintings, 45 drawings, 11 watercolors and five engravings. Frida Kahlo fervor has been strong in recent years, with her work increasing dramatically in value. Her painting “Roots,” of a young woman resting prone on barren land with green vines growing out of her torso, sold recently at Sotheby’s for 5.6 million dollars.

Millions of people around the world were introduced to Frida’s personal life and art through the fine film, Frida (2002), directed by Julie Traynor. Salma Hayak played Frida (almost a look-a-like in the film) and Alfred Molina played her husband, Mexican muralist Diego Rivera. In that movie, her sister Cristina, played by Mía Maestro, is one of the many young and beautiful models who posed for Diego Rivera and whom he later (or immediately) seduced.

That seduction – by Frida’s husband – and that betrayal – by her sister Cristina – is at the heart of Bárbara Mujica’s novel, Frida, based on the life of Frida Kahlo – artist, political activist, revolutionary, intellectual. Cristina, in Mujica’s novel, tells the story of Frida’s life (largely very accurate historically) through a first-person recounting to her psychiatrist, and throughout this long psychiatric session Cristina struggles with the difficult love-hate relationship she had with Frida. [In the Author’s Note, Mujica writes that “I was particularly interested in what it might be like to be the unexceptional sister of such an exceptional woman.”]

As a six-year old child, the already feisty (and already foul-mouthed) Frida suffered the taunts of other little girls because her father was a German Jew (although her mother was Mexican). Even her name was originally spelled the German way: Frieda. Then, still only six years old, Frida contracted polio and was bedridden for nine months. Cristina, only slightly younger, watched her sister as “her cocky, six-year-old self assuredness gave way to the excruciating shyness of the seven-year-old who knows she is different.” Because one leg was now permanently shorter and smaller than the other, expanded taunts of those other little girls now included “Peg-leg Frida!”

Mexico was in the throes of a revolution: “Mexican masses were growing poorer and poorer, and everyone said it was the foreigners’ fault. Half of the rural population lived like slaves. They owed so much to the rich hacienda owners that they had to work for free to pay it back. And most people couldn’t tell the difference between a foreigner like Papá and the bloodsuckers who were gobbling up our resources and leaving our people to rot in the fields.”

Throughout the novel, we see the forceful character of Frida displaying itself, consistent in situation after situation: “Frida,” her sister tells us, “had a kind of… almost… a sickness. Or maybe obsession would be a better word. She always had to be at the center of everything. Everyone had to be looking at her. She wanted to be different, and she was different. On the one hand, we were all different, I mean all us girls, because we had Jewish blood, and to have even a drop of Jewish blood in Mexico sets you apart, even if you’re a practicing Catholic. And in addition, she was – she’d kill me if she heard me say this – she was, well, a cripple. But both those things that really set her apart, being Jewish and being lame, she tried to cover up. She tried to convince the world that she was more Mexican than the Virgin of Guadalupe and more physically fit than Alfredo Codona.” [Alfred Codona was a popular Mexican aerialist who did triple somersaults on the high wire.]

Tragedy struck again on September 17, 1925, when Frida was riding in a wooden bus that was “bulldozed” by a trolley. Her “pelvis had three separate cracks in it, and her spinal column was broken in several places. Her right leg was shattered, her right foot dislocated, and her left shoulder thrown out of joint.” Furthermore, “An iron handrail had pierced her pelvis from one side to the other.” The attending doctor said “it’ll be a miracle if she survives.”

But survive she did, although forever thereafter doomed to a life of pain, of operations, of drugs, of orthopedic corsets. In spite of this, she became Diego Rivera’s wife, and on her own she became a celebrity whose wild life with many lovers, both men and women, fascinated the world.

Cristina tells us that Frida’s husband Diego Rivera “was the ugliest man I’d ever seen, ugly enough to win an ugly contest. A mountain of suet that had to be stuffed with a trowel into those filthy overalls he wore.” And like Frida, “He would say anything to get attention.”

Cristina tells us that Frida’s husband Diego Rivera “was the ugliest man I’d ever seen, ugly enough to win an ugly contest. A mountain of suet that had to be stuffed with a trowel into those filthy overalls he wore.” And like Frida, “He would say anything to get attention.”

Still, Cristina was fascinated with Diego… “Sex was always one of his main interests.” She adds, “Legend has it that, at nine, he had sex with an eighteen-year-old American schoolteacher, then took up with the wife of a railroad engineer. At nine years old! In spite of his grotesque looks, women found him irresistible. Even beautiful women. Just look at Frida. Just look at me.”

For Diego, sex was simple: “the man has one part, the woman has another part his fits into, and when they both feel like it, he sticks his into hers, and what’s the big deal?” For Frida and Cristina sex was not simple. It was how you asserted who you were, it was how you entertained “the rich and the famous,” it was how you showed those of lower social status that you acknowledged their equality, it was how you got even.

Their entourage included powerful politicians like “Lázaro Cárdenas, President of Mexico, Leon Trotsky, the Russian revolutionist, and the two reigning goddesses of the Mexican Screen, Dolores del Río and María Felix.

Here is a short scene between Diego and Cristina, discussing Dolores del Río (Cristina says, “Her smile made you feel inebriated.”). Diego, long after his seduction of Cristina, asks (perhaps wishful thinking) her:

- “Should I make love to her tonight?

- I didn’t answer.

- “Should I?” he insisted, crushing me against him.

- “Go ahead. Enjoy yourself.”

- “Yes, I will. Of course I will. I’ll enjoy myself more than I ever have with any other woman.”

- I tried to push away from him. I was suffocating.

- “Maybe Frida will sleep with her too. What a delicious thought, the two of them twined together, both so beautiful, so sensuous. Two female bodies entwined, the possibilities are dizzying.”

Much later, when he is involved with María Felix (Cristina says “she was the Virgin Mary and Eve all wrapped up into one.”), Frida is confronted by a reporter:

“What’s this about Diego and María Felix?” “Ah, said Frida, “so he likes screwing her. What’s the big deal? I wouldn’t mind screwing her myself!”

And what about Leon Trotsky, the aging revolutionist? When hounded by the Stalinists, he was forced to leave Russia. Mexico offered him sanctuary and Diego and Frida offered him their home, where he could also work in peace on his biography of Lenin. Diego and Frida were thrilled to be giving safe harbor to a Communist hero.

Cristina was his chauffeur: “He fell for me first. That horny old guy with the beautiful eyes.” Cristina was tempted: “I was no longer Diego’s woman. I was just one of the many women whom Diego had had affairs with. Going to bed with Trotsky would be a coup. And it would be fun. Let’s face it. I was a young single woman, and I liked to have fun. Trotsky was a character! And he had charm.”

Frida, ever alert to the various sexual energies flying around the household, began hovering over Trotsky like a “hummingbird over a honeysuckle.”

Frida wanted to get even with both Diego and Cristina. “I thought she had forgiven me, but all she was doing was biding her time, waiting for the right moment to thrust in the dagger. She wanted to punish me for having an affair with Diego, and the best way to do it was to lure away Trotsky. She would be Trotsky’s woman, not me. She had to be the star. She had to have the place of honor! And she wanted to punish Diego too. She could forgive him his other affairs, but she couldn’t forgive him for falling in love with me. And what better way to hurt him than to betray him with the man he idolized?”

Well, Frida is one fine novel. Filled with passion, with pain, with sex, with international politics, with the world of art, with the history of Mexico the first half of the twentieth century, with torrid and tumultuous and relationships, Bárbara Mujica’s novel Frida makes for some mouth-watering reading about one of Mexico’s most fascinating modern women, Frida Kahlo… although as Cristina tells her psychiatrist, the person most fascinated with Frida was Frida herself: In fact, “The only thing that really fascinated Frida was Frida. People said I was stupid. They said I never really understood what was going on. But I’m smart enough to know this: Frida Kahlo had a lifelong romance with herself, and nobody, not Diego, not me – nobody could ever replace Frida in Frida’s heart.” And of course the subject of most of Frida’s paintings is Frida.

Cristina, always in the shadow of Frida, becomes, in this novel, almost as fascinating as her older sister. And she was always at Frida’s side, in difficult times, tolerating Frida’s resentment and abuse, even when Frida had exhausted the energy of everyone else around her: “I had to be there for her. Cristina, her sister, her sidekick, her slave.”

Available from Amazon Books: Paperback