Admit it. Next to simmering on the beach or sunning poolside slathered in oil, you visit Mexico to shop. In fact, if you’re a real shopper you bypass beach resorts altogether. On at least one trip each year, you head into the interior, into cities such as Guadalajara, Guanajuato, Morelia, San Miguel de Allende, and Oaxaca. In these colonial cities, in marketplaces stocked with hand-tooled leather, pottery, woven tapestries, baskets, jewelry, and wood carvings, you can settle down to serious shopping.

On a recent trip through colonial cities, I wandered from one artisan shop to another, wondering about the rows of handicrafts, bins of trinkets and boutiques of glass and ceramica. All this “stuff” had to be made somewhere, I thought. The “somewhere” became my obsession. Instead of buying from sidewalk sellers and shopkeepers, I set out to find the artisans, the craftspeople.

I discovered that behind closed doors, and sometimes in courtyards and on side streets, cottage industries flourish. Some artisans follow a tradition of three or four generations. Others are just beginning to learn a craft–perhaps to satisfy the craving that computeroids to the north have for handmade products.

In my search, I discovered workshops, large and small, where prices are a little less than those in the more visible shops. However, my purpose wasn’t so much to get a reduced price (like you do in factory outlets in the States), but to find the people who make the products, to watch them at work.

If you don’t speak Spanish, a good place to start is San Miguel de Allende. Because of the large community of English-speaking expatriates, it’s easy to find English-speaking shopkeepers, who will often give you the addresses of workshops where products are made. This is how we found Los Originales de Papel Machier, a paper-mache factory. Owner, Pedro Hernandez-Cruz showed us around and explained that he was an artist; that it took him two months to make some of the larger, custom-ordered molds.

Each Saturday morning in San Miguel de Allende, a tour conducted by a center for handicapped children will take you to at least one “taller,” or workshop. The bus leaves at 10:30 from the main square across from the church.

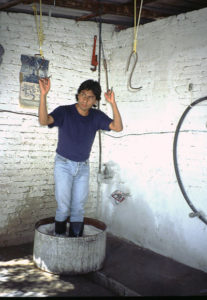

In search of a weaver, I inquired at Bellas Artes , the state art center. A teacher, who spoke some English, directed us to a two-story warehouse where young men in hip boots stomped yarn in vats of bright pink, purple, and red dyes. A friendly woman answered our knock on the black metal door and showed us around. On the second floor weavers were at their looms, adjacent to a showroom of modern, three-dimensional wall hangings. Downstairs, a delicious array of hand-dyed yarn hung in clumps on wooden pegs. I bought a kilo of grays, blues, and pinks for about $6 USD.

In Guanajuato, less than two hours by bus from San Miguel, we hired a driver and requested a tour of the city. This gave us an idea of where to go on our own. The next day, we took a bus to Las Fabricas Ceramica Santa Fe. This workshop has a display room of pottery and the manager, energetic and polite, guided us around the grounds, which included a kiln, a packaging center, and clusters of potters working indoors and outdoors.

Exploring side streets, we came upon shops where fathers were teaching their sons how to build furniture or to carve wooden animals. When we politely asked permission to watch, most were gracious and invited us in, often showing us the pieces in various stages of production.

This winter of 1998, I’m spending a few months in Oaxaca. In the surrounding pueblos, it’s customary for artisans to give demonstrations. Tourists and onlookers are welcomed. For instance, in Arrozola, families carve and paint colorful, whimsical creatures that are sold in shops in the city. Here, you buy directly from the family who make the crafts.

While wandering around Atzompa, I was invited into a home where a woman painstakingly created a clay statue. Sitting on the dirt floor of their one-room adobe home, she turned clay into figurines that I later saw in a shop in the city. The man, perhaps her husband, maybe her father, was obviously proud of her artistic ability and gave me a miniature clay figure. He wouldn’t accept pesos for it. He just wanted me to appreciate her work.

The hand woven wool rugs and wall hangings made in Teotitlan del Valle have become so popular stateside that every street in the town is lined with workshops where weavers work on their looms. In most of these, there’s someone available to explain the step-by-step process of dyeing, designing, and weaving. They’ll explain, in English, how they extract colors from vegetables, grasses, leaves, and worms.

The tourist office in Oaxaca will give you a map of the villages. Buses and collectivo taxis will take you to the various pueblos, usually for less than $1 USD. The collectivos are in marked taxi stands near the abastos market in the southwest part of the city. Or you can take a second class bus from the terminal opposite the Abastos market.

Because of the onlooking tradition in Oaxacan villages, many of these pueblos are taking on a “commercial” ambiance. The advantage of this is that you get demonstrations and a bit of insight into the craft process, whether it be weaving or pottery. However, I enjoy just wandering along side streets in the city, where I can watch an old man making guitars or an entire family involved in creating piñatas. They don’t seem to mind me hanging around as they put colorful paper around clay pots, shaping them into ducks, birds, and clowns. The pots will be filled with candies and children will scream with delight as they whack them into bits and pieces at fiestas.

If you keep your eyes open, are polite (not pushy), you’ll find people all over Mexico, making goods by hand. Watching them work at their craft gives an added dimension to buying and bartering in Mexico.