Breaking piñatas is not only a familiar element of many Mexican festivities, but a popular custom with deep historical roots. Some scholars link the practice with religious rituals of ancient Mesoamerica, while others trace it back to a Chinese custom associated with the start of the spring and the yearly agricultural cycle that was introduced to Europeans by Marco Polo.

The term piñata certainly originated in Italy, where an ancient Lenten tradition called for feudal lords to dispense gift-laden pots–called pignattas –to their serfs. The practice later spread to Spain where it became customary to romper la olla (break the pot) on the first Sunday of Lent, which became known as Domingo de Piñata.

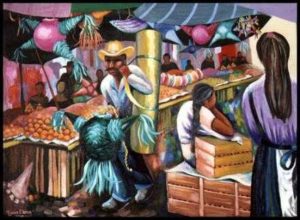

Early missionaries introduced the custom to Mexico in the immediate aftermath of the Spanish Conquest. The Augustinian friars at the Acolman convent came upon a bright idea while looking for ways to inculcate the Christian religion among the indigenous population. The interruption of agricultural labors during the Conquista had brought on widespread epidemics and famine. The frailes found that inviting the hungry Indians to take whacks at clay pots filled with peanuts and fruits was an effective method of drawing audiences to their pastorelas, the theatrical presentations staged during the Christmas season to teach the story of the Nativity.

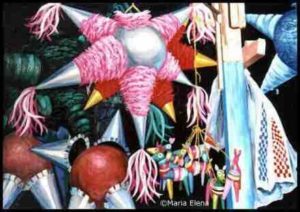

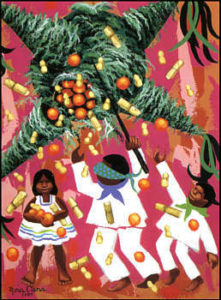

As the custom gained popularity, piñatas were made more festive by adorning them with bits of cloth and paper. Eventually the seven-pointed star–representing the seven deadly sins–became the traditional form for Christmas piñatas. The deeper meaning of breaking the piñata is thus considered to be the destruction of evil forces, the victory of good over evil. Covering the eyes of the person who tries to smash the piñata is symbolic of blind faith, which is rewarded with the pleasantries of heaven, represented by the sweets spilled from within the pot.

The piñata has become one of Mexico’s most distinctive minor art forms, crafted into all sorts of whimsical figures by adorning a crude clay pot with papier maché and brightly colored paper. For birthdays and other festivities the choices range from representations of flowers, fruits, and animals to characters from Disney films or the latest rage in kiddy cartoons. Lambs, burros, roosters, chickens, angels, wise men, Christmas trees and Santa Claus figures are popular subjects during the holiday season.

Whatever its origins, the piñata is bound to remain as a hugely popular aspect of Mexican Christmas festivities among new generations growing up in the 21st century.

(This article originally appeared in the December 11, 1999 issue of the Guadalajara Reporter and is reproduced by Mexico Connect with kind permission of the author.)