2004 turned out to be another fortuitous year for Lake Chapala.

According to data issued by the National Water Commission (CNA), accumulated rainfall registered nationwide in 2004 ran nine per cent above the previous year’s figures and 16 per cent above the historic average.

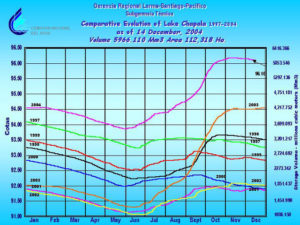

On November 1, the first day of the 2004-2005 hydrological cycle, the CNA reported Lake Chapala containing six billion cubic meters of water (6,000 Mm3), the highest storage volume recorded on that date since 1981. During the June-October wet months, the lake regained a total of 2,440 Mm3 in volume, 2.27 meters in altitude level, and 11,696 hectares (ha.) in surface area.

While this year’s gains were more modest in comparison to the dramatic recovery of 2003, the combined effect of two successive plentiful rainy seasons has propitiated a total transformation in Mexico’s largest lake. After dropping to an historic low in the spring of 2003, the lake’s storage volume increased in just six months’ time from 17 to over 53 per cent capacity. With added precipitation this year, Lake Chapala closed out 2004 at just over 75 per cent capacity.

However, the bounty of nature is only one aspect of an increasingly rosy panorama that has evolved over the past twelve months.

On March 22, incumbent governors of five states–Estado de Mexico, Queretaro, Guanajuato. Michoacan and Jalisco–joined President Vicente Fox in signing the Agreement of Coordination for the Recuperation and Sustainability of the Lerma-Chapala Basin, a pact that supplants inter-state accords that originated in 1989. Aside from renewing prior commitments, the new agreement is aimed at amplifying the scope of government actions, shifting from a primary focus on water issues to a more holistic ecosystem approach.

Terms of the pact were drawn directly from the Lerma-Chapala Master Plan developed in 2001 by the federal Environment and Natural Resources Ministry (SEMARNAT). The document calls for a wide range of actions revolving around four central axes: Institutional Legal Framework; Water Measurement and Information Systems; Water Administration and Sustainability; Ecological Rehabilitation. Social and economic factors, along with reforestation, soil conservation and clean water programs are contemplated in the package.

“On this day we initiate a strategic action to put a full stop on 50 years of deterioration in the Lerma Chapala Basin. Today we sign a pact in favor of life, health and progress,” the president declared at the enactment ceremony. “With this meeting we trace better horizons for the region. The will that we demonstrate is the spirit and attitude that Mexico requires. A spirit of commitment and co-responsibility, solidarity and fraternity.”

Brokering an agreement on a general scheme was easy in comparison to what it took to nail down one its principal elements–a total rewrite of regional water distribution policy that has been in the works since 2000.

After 70 official meetings that took up some 35,000 man-hours, plus an inestimable amount of behind-the-scenes negotiating among key players, representatives of state governments, federal agencies and water consumption interest groups who form the Lerma-Chapala Basin Council finally hashed out their differences. On December 14 the basin state governors and the president assembled anew put their signatures on a revised distribution pact that took immediate effect.

The terms of the document are based on a strategy drawn up by an independent panel of hydrologists entitled the Joint Optimum Policy (POC). Under its guidelines, the quotas for water consumption sectors are based on resource availability in accordance to annual rainfall, with fixed limits on how much water can be retained in the basin’s artificial reservoirs. Mandatory release of excess liquid captured in the dams is categorized as the chief factor that makes the POC blueprint more equitable than the previous distribution formula, and directly beneficial to Lake Chapala.

The POC is to remain in force for an indefinite period, subject to annual revision. Jalisco authorities are confident that by sticking with the new formula, Lake Chapala’s permanent sustainability can be guaranteed even in a worst case scenario for natural phenomena.

Actions emanating from the Coordination Agreement are already under way. In March, state and federal authorities announced the launch of a 13 million dollar package plan to build and up-grade sewage treatment plants along Zula and Santiago Rivers and the Lake Chapala shoreline. Major improvements to boost operations at the Chapala, San Antonio Tlayacapan and Jocotepec treatment facilities, along with a new plant at Cuitzeo near the lake’s eastern extreme, are due for completion in early 2005, translating into better water quality in the near future.

In early June, federal and state agencies again pooled resources–30 million pesos total for 2004–to initiate a long-term aquatic weed control program for Lake Chapala. Massive infestation of pesky lirio acuatico (water hyacinths) has already been reduced significantly and extraction activities remain in progress.

Perhaps the best news of all was the announcement that the federal government’s previous budgeting to upgrade irrigation systems in the nation’s agricultural zones would be doubled in 2004 and 2005. With the thirsty Lerma Basin bread basket mentioned as a major target for modernization programs, Lake Chapala will end up as a direct beneficiary of the additional funding. Around 80 per cent of the region’s surface water is currently destined to agricultural use, and about half that amount is reportedly lost due to outmoded systems and wasteful farming practices.

With Lake Chapala showing more robust health and the official sector demonstrating a growing commitment to more diligent guardianship of the region’s natural resources, 2004 brought about a corresponding shift among environmental activist groups and politicians who have been the government’s most bitter critics. Most have now toned down the rhetoric and given up organizing protest actions to focus on developing conservation programs and sustainable management projects intended to reap long-term benefits.

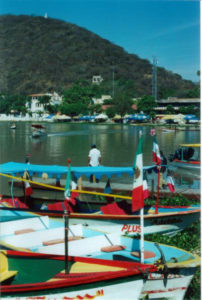

Lake Chapala’s revival has likewise boosted prospects for the local economy. Promising signs include rejuvenation of the tourist trade, reactivation of the fishing industry and a booming real estate market.

Gazing at Lake Chapala at the dawn of 2005, it’s hard to conceive that just two years ago it looked like a giant mud puddle gasping for a last breath of life. As water has finally spread over almost the entirety of the basin, the desolate vision a vast, arid shoreline begins slipping away into memory.

No one can say for sure how Lake Chapala will fair over the next twelve months and in years to come. Yet, witnessing the famed inland sea return to conditions absent for nearly a quarter of a century is certainly reason enough to maintain a degree of optimism for its future.

Further References:

- Lake Chapala 2003 — A Season of Hope

- Huichol Voices 2003 Re-connecting with the Lake – C. J. English

- Can Mexico’s Largest Lake Be Saved? Part 1 – An examination of Lake Chapala – Tony Burton

- En Español – ¿Se podrá salvar el mayor lago de México? – Tony Burton

- Can Mexico’s Largest Lake Be Saved? Part 2 – A Year 2000 Update: The State of The Lake. – Tony Burton

- Can Mexico’s Largest Lake Be Saved? Part 3 – A Year 2001 Update: Suggestions for Discussion – Tony Burton

- Can Mexico’s Largest Lake Be Saved? Part 4 – A Year 2002 Update: Eco-Chapala – Fish, Farm, or Bungee Jump? – Tony Burton