This month’s cover is a digital photo of papier-mâché chili peppers taken in Ajijic. These strings of papier-mâché items are known as ristras and are just one of several Mexican paper, art forms. Typically, ristras are fruit, vegetables, garlic, birds and other animals. Paper crafts have a long history in this country. Everywhere you look there are paper articles colorfully winking at us, “This is Mexico!”

Papermaking is an ancient craft. In pre-Columbian times, deer skin, tree bark and agave or maguey fibers, were fashioned into forms of paper used for painting pictorial manuscripts for religious or historical purposes. Some of these papermaking skills have survived today and are to be seen in popular art, as well as in healing rituals. Paper called amate is made from the bark of mulberry and fig trees, most notably in the town of San Pablito, Puebla. The mulberry produces a whitish paper, while that of the fig is dark.

Men of the village peel the bark from trees, but the women actually make the paper. The bark is washed, boiled in a large pot for several hours with ashes or lime, then rinsed and laid in lines on a wooden board. The fibers are next beaten with a stone until they fuse together into paper and are left to dry in the sun. The high demand for amate paper has resulted in the over-stripping of trees and even the poaching of bark.

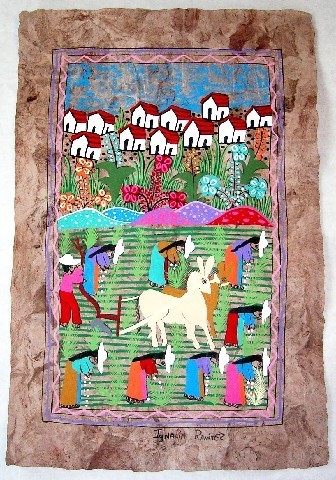

Much of the amate paper goes to villages in the state of Guerrero, where artisans who once decorated pottery, now paint imaginative scenes of everyday life, fanciful birds, animals and flowers on this special paper. Such paintings of varying quality are produced in abundance for the tourist trade. Some works are signed and occasionally, a gifted artist may gain considerable recognition for his work.

In San Pablito, amate paper is used by shamans for making cutouts of spirit beings associated with the sky, the earth, the underworld and water, for healing and fertility ceremonies. The shaman will bring them to life by breathing into their mouths, holding them in the smoke of incense or sprinkling them with alcohol. These cutout figures in dark and light shades of amate are sometimes mounted and sold to tourists and collectors or even made into accordion-type books that explain the mystical ceremonies. Beside amate paper, ordinary tissue paper-cutouts of the spirits are also employed in rituals and books to provide an accent of color.

Tissue paper is the basis for another art form, papel picado, in which multi-layered sheets of colored paper are cut out from a pattern to make banners. These popular banners are ordered for local fiestas, birthdays or home decorations and may depict flowers, leaves, birds, angels, crosses, or anything specified. Increasingly, the banners are made to represent skeletons in an infinite variety of activities and are sold for the Day of the Dead, November 2nd. Originally, papel picado was laboriously cut out with scissors, but now artisans use sharp chisels to cut through as many as 50 sheets of the tissue paper from a basic pattern. When we drive by streets covered with these tissue paper flags, we don’t realize that not only are they a Mexican art form, but could have deep religious significance as well.

Papier-mâché figures of all kinds are created for every occasion, celebrating the Day of the Dead, decorating homes, creating monsters to burn for Easter week. The colors and forms are limitless.

You can get ristras like the chile peppers featured on the cover, as well as a variety of other colorful shapes, at Juanita Banana, Centro Artesanal, located on 16 de Setiembre in Ajijic. They are sold by the string for roughly 60 pesos each.

This article appears courtesy of the Chapala Review, a monthly Newspaper published in Ajijic, Jalisco, Mexico. The focus is the Lake Chapala area. The goal is to provide quality information about the area, its stories, events, history, culture and people.