Mary Jane Gagnier Mendoza

Day of the Dead in Mexican folk art © Mary Jane Gagnier Mendoza 2003

For foreigners, the traditions and celebrations in Mexican homes and cemeteries during the Day of the Dead seem strange, if not incomprehensible. There is mourning and rejoicing; sadness and silliness – woven together into one emotional fabric.

To me, it’s like welcoming the return of a dear friend or relative, who moved far away and visits just once a year. Mexicans try very hard to be with their families for this fiesta, as the living and the dead gather for the most complete of family reunions.

The Day of the Dead activities actually span several days, beginning late at night Oct. 31, when the spirits of dead children (angelitos) start arriving, followed by adult spirits sometime during Nov. 1. They leave, after joining in a family meal, on Nov. 2. Although exact times for the spirits’ entrances vary from pueblo to pueblo, the angelitos always arrive ahead of the adults.

I grew up in a French-Canadian Catholic family. From an early age, I believed that when you died, you put on a white satin smock with lace around the cuffs and joined the anonymous army of souls (in heaven if you were lucky).

Mexicans have a distinctly different view of themselves in the afterlife. First, you keep your identity, since to return to this world for the Day of the Dead, you must remain who you were. This explains the profusion of skeletons of all sizes, doing ordinary day-to-day things. If uncle José was a barber, he continues as a barber after death. Placing a skeleton figure of a barber on your altar reaffirms to uncle José that he has not been forgotten on his spiritual return.

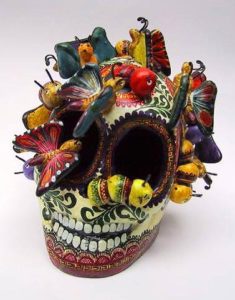

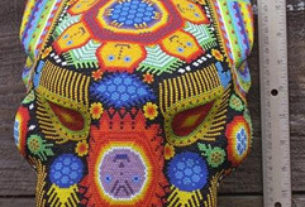

Most Oaxacan homes have a highly adorned Day of the Dead altar. Sugar skulls with the names of dead loved ones inscribed in their icing indicate to the returning spirits that they have indeed returned to the right spot, where the living await their arrival. The altar is a sort of landing pad and its objects serve as signals to guide the spirits home.

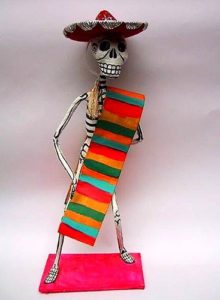

Throughout the year, but especially during the Day of the Dead season, calacas, or skeletons, are displayed in shops throughout the city. In the Abastos market, for a few pesos each, you’ll find cardboard, wire and cotton-ball figures depicting nearly every walk of life. The more upscale folk art stores display elaborate ceramic and paper mache calacas, individually signed by renowned Mexican folk artists.

Duality in Mexican Folk Art

The skeletons and skulls of Mexican folk art reflect the dualism fundmental to the pre-Hispanic world view. Without duality in all aspects of life, the universe loses its equilibrium. Animal and human forms; masculine and feminine energies – all are needed. Of all these balancing forces, perhaps none is more significant than that of life and death.

Images expressing dualities abound in Mexican folk art. The Nahuals of Oaxacan woodcarvers, for example, are supernatural beings that transform back and forth from animal to human form and from human to animal form. The belief in Nahuals is well-documented in indigenous folk culture. However, if a survey were taken among Mexico’s folk artists, the combined imagery of life and death – la vida y la muerte – would emerge as the most popular and pervasive theme.

The iconographic image of the living and dead sharing a single body or head remains a common visual theme in Mexican folk art. The reason is simple: for the Mexican, life and death are part of the same linear process. Birth leads into life, and life leads to death. Join the ends of the process and the cycle of life is created.

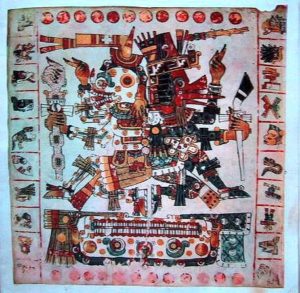

The roots of this duality are ancient and deep. The Borgia Codex depicting pre-Hispanic life shows two gods: Quetzalcoatl, the god of life who governs the earth and sky; and Mictlantlecuihtl, the god of the underworld and keeper of the dead. They appear in profile, joined at the spine. At first glance, they seem a single form. Two distinct shapes then define themselves, one complementing the other and the two together forming a complete whole. Each, we learn, needs the other to justify its existence.

The Altars and the role of ephemera

No exploration of the Day of the Dead would be complete without a discussion of the empheral creations used in its celebration. Most of the elaborate Day of the Dead altars found in Oaxacan homes are adorned with authentic works of art meant to last no longer than the fiesta itself.

To Western culture oriented to preserving everything as long as possible, it may seem strange to expend so much labor on objects having no other purpose than to be consumed and destroyed. Mexicans, especially indigenous Oaxacans, see themselves as empheral beings in an empheral world. To enjoy material objects, yet be willing to relinquish them, is totally natural to them.

Nothing is more empheral than the sugar used to make elaborate skulls, angels, and animals for the Day of the Dead. Saving these items for the following year would never occur to Oaxacans. Children used to wait all year for parents to buy them calaveras de azucar with their names inscribed in the icing. Today, chocolate skulls are replacing the sugar ones, but the tradition of eating sweet skulls is as alive as ever.

Papel picados – intricately cut tissue paper banners depicting scenes of skeletons dancing, drinking and otherwise celebrating – are strung along the edge of altars, creating a lacey border. Non-Mexicans often ask how to preserve them. “You shouldn’t,” I say, “because they were never made for that.” Such emphemera celebrate other events and fiestas as well. White tissue paper is used for weddings. Red, white and green commemorate Independence Day. A riot of color surrounds the Day of the Dead. When fiestas end, papel picados are left to fly in the open air until rain reduces them to nothing.

Flowers, candles and incense are indispensable to any lovingly adorned altar. Wax flowers, fruits, and cherubs decorate hand-dipped beeswax candles. As the candles burn non-stop, the wax decorations are set aside to be melted for the next batch of candles.

The Toymaking Tradition

A thriving tradition of toymaking plays a central role in the Oaxacan Day of the Dead. Among such diverse themes as the Nativity, bullfights and carnival rides, the skeleton is by far the most popular image. Mariachi calaveras in the form of puppets made of painted plywood and string are special favorites among small children. Who knows what makes skeleton toys funnier than toys depicting the living? Maybe it’s the surprising juxtaposition of the dead doing something lively and spirited that brings a chuckle to the most sober face. Perhaps by making death more approachable through friendly images, like a dancing skeleton playing a guitar, Mexicans begin to lose their fear of death at an early age.

The Spirit of Posada

The name Posada and lively skeletons are linked as few other icons of contemporary Day of the Dead culture. Jose Guadalupe Posada (1852-1913) popularized Mexico’s life of the dead in bitingly satiric, mass-produced etchings and lithographs that have enthralled Mexicans for generations.

By depicting social and political personalities as calaveras, Posada’s posters achieved lasting and unrivaled popularity. By caricaturing his targets in their bare bones, his scathing and often risky political satire became funnier and thus more acceptable.

In his posters, priests, politicians, farmers and streetsweepers share the same destiny – death, an end neither money nor power can outwit. For a country living in extreme social inequality during the Porfirio Díaz dictatorship, the idea of the rich and poor alike one day rubbing elbows (if only bone to bone) was attractive to the masses.

Posada’s handprinted calaveras, accompanied by witty social commentary in rhyming verse, reached the farthest corners of the Mexican Republic. To this day, his work pervades the image and spirit of Mexican folk artists. The Catrina, an upperclass lady of the turn-of-the-century always depicted in her broad-brimmed hat, has become a classic in Mexican folk art and is displayed prominently in many store windows. The images can be found in everything from fine ceramic and artistic paper mache figures, to inexpensive papel picados and plaster miniatures.

Nothing is static about Posada’s calaveras (mischievous skeletons). They are always up to something, going somewhere or, as in the Calavera Oaxaquena, just raising hell.

The Calavera Oaxaquena

The valiant calavera

Has just arrived today.

Take off your hat and greet him.

Don’t look at him that way!

In Oaxaca they pay for bravery

With a hooter of mezcal.

And without a single rival

Are their beautiful young gals.

No one ever scares me.

At them all I do is guffaw.

And to prove this I danced a two-step

Upon a dandy from Guadalajar.

The Oaxaca calavera

Has just arrived today.

Take off your hat and greet him

Because he’s here to stay.

For all of you who like to travel, be assured that in the afterlife you’ll get a chance to come back, kick up your heels with loved ones and, like the Calavera Oaxaquena, raise hell. So three cheers to the life of the dead – in Mexican folk art!