Travels With Travis

Inspired by the caricatures of lithographer Jose Guadalupe Posada, the elegant Catrina has her origins in Day of the Dead celebrations. Capula’s Catrinas arrived only recently.

They stand in the doorways of this small quiet colonial town, Catrinas of every size and description decked out in flowered dresses and clenching flowers in their cratered teeth, plumed hats adorning their slick skulls. These skeletal specters, naked of skin, beckon visitors with their charms, sharing their space with clay pots, dishes, bowls, and cups to serve their eager guests; kitchenware embellished with the town’s trademark florets – the popular punteada barro for which Capula is also famous – whirling in small airy circles as they shimmer around the pieces, creating a sensation of pristine timelessness. As in the town of Cuanajo, they fill the doorways with treasures of attractive and practical use, but the smooth corners and rounded edges of plates, bowls and pitchers gently flowing into each other create a more placid effect.

Rolling slowly down Calle Vasco de Quiroga, Capula’s main drag, visitors are greeted by flowers popping from clay pots, blue-green suns with lips lined in gold, clusters of small pitchers hanging from string, and clay masks of feathered Indians. The Mercado de Artesanias has a broad variety of locally-produced goods: lamps and flower pots pierced with suns; glazed dinner sets; pitchers; butterflies caressed with licks of fire; pots with calla lilies and suns on backgrounds saturated in blue; candleholders cut with radiating lines of flowers; bowls sparkled with circles of pink and white and yellow whirling across the hips. A wall-hanging depicts a horned blue moon with a mop of green hair kissing a more hesitant moon.

Capula’s Catrinas arrived only recently, courtesy of Juan Torres who began creating these curious figures several years ago. From that singular influence the craft has diversified into a multitude of fanciful illusions. At the Mercado de Artesanias, you’ll find Catrinas in black garb wearing elaborate hats adorned with flowers, gaping grins, and beehive hairdos. A pot-bellied Catrín (the male version, its name meaning “a dandy”) clothed in mariachi garb holds a rooster; a small platoon of grinning Catrinas wear mermaid tails and bear flowers. Two dress up in magenta dresses and gold-trimmed aprons with heavy pots strapped to their backs.

Artesanias Relatos de la Abuela (“Grandmother’s Stories”)have much taller Catrinas than you’ll usually find, with flatter skulls and protruding lower jaws, fashionably dressed in formal evening gowns standing next to suited-up Catrines, all wearing ammo belts and bearing rifles at present arms. Behind them stands a Catrina with her chest stuck out and showing her brittle leg through a slit in her dress; still another has real lace trim around her hat and dress.

A few blocks away, Maria de los Angeles and her husband, Francisco Barocio Jacobo, labor away in the little shop next to their home on an order for fifteen Catrinas dressed to resemble Frida Kahlo. Maria’s crescent lashes veil the warm glow of her sparkling brown eyes as she presses tiny florets into slivers of wet dough with a home-made clay pattern to make flowers for the dresses.

Francisco, in baggy brown corduroys, use small makeshift tools to cut lines of feathers and eyes into the parrots he pins on the Catrina’s dress. He and his wife have an intimate connection with the clay, as if they know exactly what the material needs to release the energy within its formless mass. From their meticulous, tedious activity emanates a sweet nectar spilling from their souls; it’s a primal luxury of invention, this opportunity to reach into the very marrow of the collective human consciousness and extract at least a shadow of its reality, softening the hot hunger of death with a moment of ridicule at its most sinister visage, the human frame stripped of its pulse and dressed for a dinner party. In the world of the Catrina, nothing can stop the festival of life, not even the specter of permanent decay.

“The first thing I started making were little bulls and horses, small things,” says Francisco, a moustache spilling over the corners of his mouth.

“I started making the Catrinas when I was thirteen, maybe a year after I started working.”

Making Catrinas is not something an artisan learns to do overnight. Francisco learned the craft through many difficult attempts.

“It was all hard. When I made my first Catrina, they came out to be not so fine.”

His wife also began working in clay at about age twelve.

“Before I got married, at my house we used to work at making flower pots. We didn’t make the Catrinas.” She enjoys making the figures, although they require substantially more work.

“It’s more tiring. Before I got married, it was 6 o’clock when I stopped. Now it’s more like 10 p.m.”

“We start at 7 a.m.,” adds Francisco.

Back on the main drag, Laura Neri Espinosa paints a plate at Alfareria de San Francisco, the family’s store and studio where she and her husband, Rogelio Martinez, do their work. “I learned from my grandparents” says Laura. “It was passed from generation to generation. It’s been changing. It depends on what people want. My grandparents started making the Tarascas with clay. It was glazed and painted and used as fruit bowls. We make plates with Catrinas, flowers, different designs. My inspiration, I paint the monarch butterflies, which is the ideal of Michoacan. Also the fish of Lake Patzcuaro.”

Curved like quarter moons with complexions of pale azure and subtle gold, the “fish of Lake Patzcuaro” swim around the edge of a large plate with blue trim, their mouths aimed at the center. All the plates created by Laura and Rogelio – many of them purely decorative – are created in a mold; the two artisans express a part of their humanity through the painting of their pieces.

Fish, blossoms, and birds dance around glazed pitchers and flower pots; plates are decorated with papayas and melons swirling in a circle and hummingbirds probe calla lilies hanging on the walls. Catrinas wander through waves of butterflies on other plates, along with likenesses of gaping skulls clothed in flowered hats. A frowning Catrina dressed in a purple dress with orange diamonds stands with arms angrily folded across a plate that required eight days for completion. Her lower lip pooches out as she glares crossly at a Catrín kneeling at her feet, his clasped hands begging forgiveness, a tattered black hat crowning his head.

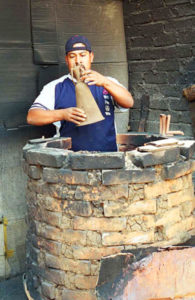

On another day, Laura has left to run an errand, and Rogelio is working away at some plates. Rogelio, who jabs an object mounted with metal studs into a container of kaolin and then presses them into a plate, says he learned the craft from his parents; he’s been involved in the trade for twenty years. He uses designs – Catrinas and colibrís (hummingbirds) – that differ from what his parents use.

“I don’t want to have competition with my parents. We have completely different clients. I like the drawing and the painting, it relaxes me. Molding is a lot of work and very difficult, and it’s very tiring.”