A great ideological struggle is never a day at the beach. Whether its matrix is race, nationality or economic inequality, the fight of the oppressed against the oppressor is always a somber affair. Nobody realized this better than José Clemente Orozco. Born at a time when Mexico was ruled by a seemingly revolution-proof dictator, Orozco was in an ideal position to depict how difficult would be the effort of the Mexican people to obtain social justice. And, with the possible exception of Goya, no artist depicted the human condition of his times with more passion and skill than Orozco.

The artist was born in the Jalisco town of Zapotlán el Grande (today Ciudad Guzmán) on November 23, 1883. His family moved first to Guadalajara and then to Mexico City, where he arrived in 1890. As noted in my coverage on José Guadalupe Posada, one of that great satirist’s disciples was young Orozco. Orozco was inspired to take up art as a career after seeing some of Posada’s engravings.

He began classes at the San Carlos Academy but at first wasn’t convinced that he could make a full-time career out of art. So he studied agriculture for three years, only to return to the academy in 1906 and remain there until 1910.

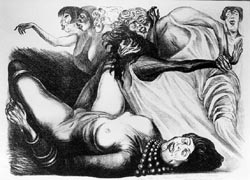

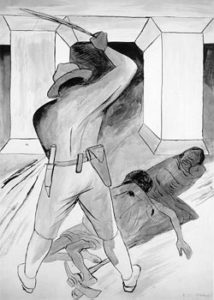

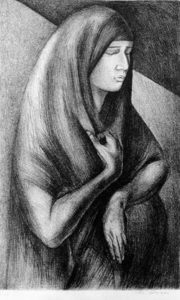

Between 1910 and 1916 Orozco drew cartoons for the magazine El Hijo de Ahuizote and was one of a group of politically oriented artists on the staff of La Vanguardia, organ of the Constitutionalist movement during the Revolution. He also did watercolors and oils, these attacking, in the words of his own political metaphor, “the pestilential shadows of closed rooms.” Like the artists of the Renaissance, Orozco wanted to let in air and light. His drawings contained scenes of the Revolution and his first great portrait, shown in 1915, was titled “The Last Spanish Forces Leaving the Castle of San Juan de Ullúa.” This was a reference to the Independence War, in which that grim castle in Veracruz harbor was the last Spanish stronghold. Orozco went to the United States in 1917; on his return he painted “Soldadera,” celebrating the women soldiers of the Revolution, “Combat” (also about the Revolution) and a picture of his mother.

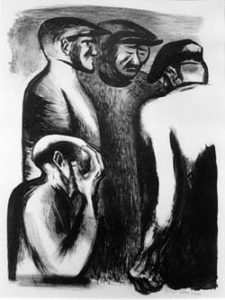

1922 found Orozco heavily involved in mural painting. Several of his murals appeared in the patio of the National Preparatory School, formerly the Jesuit institution of San Ildefonso. These include “The Elements,” “Man in Battle Against Nature,” “Christ Destroys His Cross,” “Destruction of the Old Order,” “The Aristocrats,” and “The Trench and the Trinity” — in this case, the worker, the soldier and the peasant. Other pictures at this location depict negative forces (in a negative light) and the human tragedy of the Revolution. In 1925, at Mexico City’s House of Tiles, he painted the mural “Omniscience”; the following year, at the Industrial School in Orizaba, Veracruz, a mural depicting conditions in post-revolutionary Mexico.

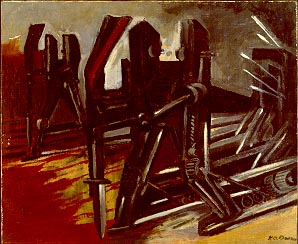

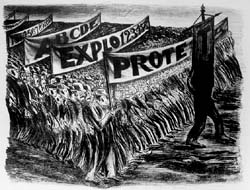

Between 1927-1934 Orozco lived in the United States. In New York his pictures embraced two themes: the Mexican Revolution and the mechanization and dehumanization of life in a great metropolis. In 1930, at the New School for Social Research, he painted murals celebrating fraternity, world revolution, labor, the arts and sciences and the struggle against slavery. For the Baker Library at Dartmouth College, between 1932-1934, he contributed a group of frescos, including “Migrations,” “Human Sacrifices,” “The Appearance of Quetzalcoatl,” “Corn Culture,” “Anglo-America,” “Hispano-America,” “Science” and another version of “Christ Destroys His Cross.”

On his return to Mexico, Orozco worked in Guadalajara between 1936 and 1939. In the vaulting of Government Palace he painted such celebrated frescos as “The People and Its Leaders” and, on the staircase, his picture of Miguel Hidalgo, father of Mexican independence, holding a flaming torch.

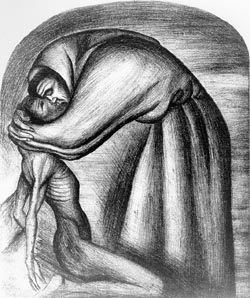

Orozco reached the summit of his art with the frescos he painted for the Guadalajara’s Hospicio Cabañas. These include a historical panorama of Mexico showing the pre-Hispanic world of the great Indian civilizations, the Conquest, visions of the downtrodden, public service as opposed to demagoguery, the perils of alienation and dictatorship, the Revolution, creative activity and a man engulfed in flames. The latter evokes a Promethean theme and recalls a 1930 Orozco creation, “Prometheus,” that is the property of Pomona College in Claremont, California.

In 1940 Orozco decorated the Gabino Ortiz Library in Jiquilpan, Michoacán, birthplace of President Lázaro Cárdenas. Between 1942-44 Orozco decorated the Hospital de Jesús in Mexico City and also combined easel painting with portraits and ballet decorations.

One of the artist’s final works, in 1948, was “Juárez Reborn,” a huge portrait depicting the great statesman leading a torch-bearing band of republicans against the aristocracy and clergy. Above the scene is the shrouded cadaver of Maximilian.

Throughout his career, Orozco combined painting with drawing and lithography. With his revolutionary political views, he was a superb political cartoonist. One of his best selections, “The Scandalmongering Press at Noon,” depicts the opportunistically changing attitude toward Pancho Villa of a figure representing the sensational press. In the first reel Villa is just a speck on the horizon and the figure is shouting, “The bandit Doroteo Arango” (Villa’s real name.) The second reel shows Villa a little closer and the figure, now more restrained, saying, “The ringleader Pancho Villa.” In the third reel Villa is even closer and the figure, now decidedly nervous, is saying, “The rebel Francisco Villa.” The final reel shows Villa center stage with Mr. Scandalmongering Press kneeling at his feet. The caption (no translation necessary) is: “Sr. General don Francisco Villa.”

Henry James, hearing Balzac described as a French Dickens, said “Yes, but a very French Dickens.” James explained the qualifier by noting that each writer was deeply rooted in his own national consciousness and Balzac would have been as incapable of producing a Wilkins Micawber as Dickens a Père Goriot.

While painting and writing are different disciplines, it is astounding how much Orozco resembles both Dickens and Balzac in prodigiousness of output and in his role as an interpreter of national values. Revolutionary wall painting — the trademark of Orozco and such contemporaries as Rivera and Siqueiros — is as evocative of Mexico as A Christmas Carol of 19th century London and Eugénie Grandet of provincial France.

In the area of political activism, Orozco’s last hurrah came in June 1948 when he accompanied Diego Rivera, Frida Kahlo, David Alfaro Siqueiros, Gerardo Murillo (“Dr. Atl”), Juan O’Gorman and other left-wing intellectuals in a raid on the Del Prado Hotel. Their purpose was to restore the words “does not exist” to a Rivera mural which had been effaced by right-wing Catholic students. (The original logo was “God does not exist.”) Orozco died on September 7 of the following year. He is buried in Mexico City’s Rotunda of Illustrious Men.

Collections of his drawing and paintings can be found in the Carrillo Gil Museum in Mexico City and the Orozco Workshop-Museum in Guadalajara.