Did You Know…?

Strange but true; the bird now so closely associated with many festive meals is a direct descendant of the wild turkeys still found in many parts of Mexico. How is it possible that a Mexican bird acquired the name turkey?

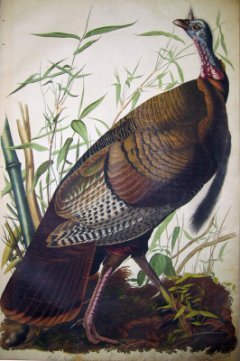

Turkey

Painting by John James Audubon, 1830

The most likely explanation derives from the fact that the merchants who traded in the Middle Ages between the Middle East and England were based in the Turkish Empire and hence known as “Turkey merchants”. Turkey merchants are believed to have introduced the guinea fowl, a native of Madagascar, to European dinner tables.

Later, the larger New World bird, the present-day turkey, was brought back to Spain by the conquistadors. The rearing of New World birds gradually spread to other parts of Europe and North Africa. The Turkey merchants capitalized on the new opportunity, and began to supply the new birds instead of the guinea fowls to the English market, and the rest is history.

The first use in English of the word “turkey” to describe the bird dates back to 1555. By 1575 , turkey was already becoming the preferred main course for Christmas dinner. Curiously, the Turkish name for the turkey is hindi, which is probably derived from “chicken of India”, perhaps based on the then-common misconception that Columbus had reached the Indies.

Mexico’s wild turkeys had been domesticated by pre-Columbian Indian groups long before the Spanish conquistadors arrived. Several archaeological sites provide tantalising clues as to precisely how turkeys were reared. One such site is Casas Grandes in the northern state of Chihuahua, an area where modern, large-scale turkey-rearing is an important contributor to the local economy.

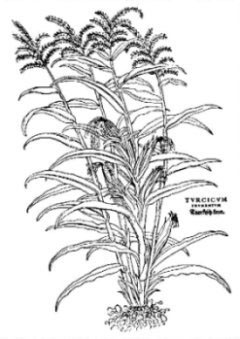

Corn

According to Ernst and Johanna Lehner, corn, which also originated in Mexico, was misnamed as Turkish corn at the same time, and for much the same reason. Europeans first saw corn, called maize or mahiz by the indigenous people, when Columbus and his followers arrived in the New World. They took samples back to Spain at the very end of the 15th century.

It quickly became an important crop, successfully cultivated throughout the continent. 16th century herbalists in Europe called the new plant by various names, including Welsh corn, Asiatic corn, Turkish wheat and Turkish corn. The latter name was the most usual, since they believed that the grain had been brought into central Europe from Asia by the Turks, who had introduced dozens of other products from the east into Europe at about the same time.

The Turks themselves called the crop “Egyptian corn”; the Egyptians called it “Syrian sorghum”… The German botanist Hieronymus Bock, in his New Kreüterbuch or herbal in 1546, remained on the fence, calling it “foreign corn”. Given the confused terminology, perhaps it is not surprising that, to quote Ernst and Johanna Lehner, “It took Spanish botanists more than 50 years to convince other European herbalists that corn was American.” Corn was given its botanical name, Zea mays, by Carl von Linné in the 18th century.

Potatoes

Alongside turkey and/or corn at Thanksgiving and Christmas, the humble yet versatile potato is often eaten. That, too, was introduced to Europe from Mexico. A previous Did You Know? delved into the connections between Mexico, the potato, and the Irish migration to North America following the potato famine of the early 19th century.

But did you also know that potatoes were originally sold in Spain on the strength of claims that they could cure impotence, at prices up to two thousand dollars a kilo?

Nowadays, potatoes in one form or another are virtually ubiquitous – from mashed or baked or potato salad, to French fries and the quintessentially Québécois variation of poutine (fries, curds and gravy).

The first Thanksgiving

My esteemed colleagues Don Adams and Teresa Kendrick have presented a strong case that the very first Thanksgiving celebration by Europeans in North America was held not in the U.S. at all, but in Mexico, on April 30, 1598.

This date certainly precedes the claims of Plimoth Plantation, Massachusetts, site of the 1621 thanksgiving, and negates the latter’s claim to the be the birthplace of Thanksgiving. One curious historical footnote is that the feast on that occasion apparently did not include either turkey or potatoes!

Pumpkin Pie

And how could you have pumpkin pie without the pumpkin? All varieties of pumpkin, whatever their size and shape, belong to the Cucurbita genus. While there are some doubts about the precise origin of the wild forms of pumpkin, they were certainly being cultivated in Mexico as long ago as 5500 B.C. and were an integral part of the daily diet of many Indian groups. The use of “pumpkin” in English can apparently be traced back to 1547. For many people, pumpkins are eternally associated with both Thanksgiving and with Halloween.

Christmas Poinsettias

Putting menu details to one side, Christmas in North America would not be complete without the finishing splash of color provided by another Mexican native: the Poinsettia.

© Tony Burton, 1999

This beautiful plant, with its colorful bracts, has become indelibly associated with the season. Most people who buy indoor pots of Euphorbia pulcherrima, commonly known in Spanish as Flor de Noche Buena (Christmas Eve Flower), probably do not realize that the plant in its native habitat grows as high as a small tree. Poinsettia, its English name, honors Dr. Joel R. Poinsett, a U.S. diplomat who served in Mexico in the 1820s. While most poinsettias have modified leaves or bracts that are scarlet- or vermilion-colored, other varieties have pink or even white bracts.

So, wherever you are this festive season, keep your eyes open for Mexican influences…

Many traditional Thanksgiving and Christmas dinners would simply not be the same were it not for a few key ingredients from Mexico!

¡Feliz Navidad! Seasonal greetings to all!

Sources:

Lehner, Ernst & Lehner, Johanna. Folklore and Odysseys of Food and Medicinal Plants. New York: Tudor Publishing Company. 1962.

Don Adams and Teresa A. Kendrick. “Don Juan de Oñate and the First Thanksgiving”. Don Mabry’s Historical Text Archive. Retrieved on 2008-07-13.

Elizabeth Armstrong (2002-11-27). “The first Thanksgiving”, Christian Science Monitor. Retrieved on 2008-07-13.

Online Etymology Dictionary. Acessed 2008-07-13.