Did You Know…?

In the golden age of steam, railway lines were built all over Mexico. Rail quickly became THE way to travel. Depending on your status and wealth, you could travel third class, second class or first class. Anyone desiring greater comfort and privacy could add their luxury carriage to a regular train. To avoid mixing with the ordinary folk, the super-rich and the privileged few hired or ran their own special trains.

The railway era ushered in an entire new genre of travel writing, which culminated in the first genuine guidebooks, describing routes and places that other travelers could visit with relative ease. The earliest comprehensive guide to Mexico was Appletons’ Guide to Mexico (1883); it was soon followed by several others including Campbell’s Complete guide and descriptive book of Mexico, first published in 1895.

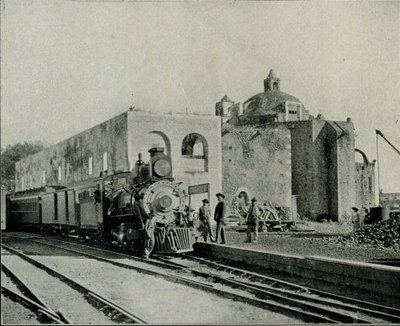

The Mexico City-Puebla line was completed in 1886 and went via the small town of Cuautla in the state of Morelos. Cuautla is about 25 kilometers south-east of Cuernavaca.

In Cuautla, the builders of the railway found a perfect location for the town’s new station, very close to the center. They modelled the station around the cloisters of an abandoned building, the former Dominican convent of San Diego, which dated back to 1657. Its ecclesiatical life ended some years before parts of it were incorporated into the railway station in 1881.

The 1899 edition of Reau Campbell’s famous Guide provides an idea of what visitors to Cuautla could expect when the train was in its heyday:

Here again the tourist finds another feature of Mexico’s scenery and people, totally different from all the other travels in the Republic. The houses are adobe as to walls and thatched as to roofs; the broad plains have curious trees; bands of Indians troop from one town to another in curious costumes, marching along totally oblivious to the passing locomotive and approaching civilization, and will not give way to the latter any quicker than they will to the engine if they happen to be on the track when it comes along. In fact, it is hard for them to understand that the train cannot “keep to the right” when it meets people in the road, and they claim the right of way from the fact that they were there first.

Now the sugar country is reached. The train passes through a fine hacienda and backs into Cuautla on a Y, passing and crossing an aqueduct, where the natives are seen bathing and washing clothes, comes to a station that was once a church.

The train stops some minutes in Cuautla and there may be time for a walk through the little alameda, just outside of the station, where there are trees and flowers, a hotel where there are good wines, coffee and lunches to be had. As the approach to the station has been through a grove of tropical trees and gardens, so is its departure, and the train continues southward through the cane country to Yautepec…

A decade later, the British-born journalist William English Carson (1870-1940) spent four months in Mexico. Despite being an enthusiastic traveler, many of his views about Mexicans will strike modern readers as stereo-typical. For example, he dedicated an entire chapter to The Mexican Woman, which makes for fascinating reading despite many statements which read today as outrageous over-generalizations, such as “no foreigner, unless he be associated with diplomacy, is likely to have any chance of studying and judging the Mexican women”; “the Mexican girl has but two things in life to occupy her, love and religion”; “As a rule, the Mexican women are not beautiful”. As we saw in an earlier Did You Know?, the latter claim can swiftly be disposed of considering the considerable beauty of many girls from Sinaloa!

Carson visited Cuautla as result of catching influenza and visiting a doctor in Puebla:

“Try Cuautla,” said the doctor when I consulted at Puebla; “there’s nothing like it in a case of influenza with bronchial complications.” My first thought was that Cuautla was some strange Mexican drug, and I was wondering whether it would be a nauseous dose, when the doctor proceeded to enlighten me. “Cuautla,” said he, “is the name of a popular health resort between Puebla and Mexico City, the climate of which does wonders for sufferers from lung and bronchial troubles.”

Upon making inquiries at the railway office about trains to Cuautla, the clerk handed me an illustrated pamphlet with a fine colored picture on the cover representing a Mexican tropical scene. It bore the title, “Cuautla, Mexico’s Carlsbad.” What! I thought, another Carlsbad? In glowing language the booklet described Cuautla as an earthly paradise with a magnificent climate, beautiful scenery, splendidly equipped hotels and a warm sulphur spring whose waters were a certain specific for almost every human ailment. What more could one desire?

Carson continues:

Cuautla is about a hundred miles or so from Puebla, and the speedy trains of the Interoceanic Railway take about ten hours to make the journey. The train which I took left about seven o’clock in the morning ; it was not timed to reach Cuautla until five in the evening; and as there was not any restaurant at any intermediate station, a somewhat terrifying prospect of starvation faced travellers. How were they to get their luncheon? A little pamphlet given away by an American tourist agency and evidently written by an accomplished press-agent gave me the desired information:

“At a certain station on the road,” said my traveller’s guide, “your train will stop for some twenty minutes. Here you will be greeted by graceful Indian women,— beauties, many of them, with their olive skins and dark, flashing eyes, bearing themselves with queenly grace in their dainty rebosos and flowing garments, white as the driven snow. They will offer you such dainties as tamales, chili-con-carne and tortillas, piping hot from their little stoves, and prepared with all the scrupulous cleanliness of a Parisian chef. They will bring you dainty refrescos of freshly gathered pineapple or orange to quench your thirst, and pastry such as your mother may have made when her cooking was at its prime.”

Now, what more could any reasonable traveller demand? What need was there for a restaurant when there were all these good things to be enjoyed? I showed my guide to an American friend before I started. He chuckled, gave a knowing wink and remarked, “Great is the faith of man, for after all your experiences you can still believe in a Mexican guide-book.”

Carson finally made it to Cuautla, and found a hotel: On my arrival there, I crossed a pretty little plaza opposite the station and reached the Hotel Morelos, an establishment under American management where I had arranged to stay. It was the usual old mansion that had been turned into a hotel and very little altered. There was a large interior patio, with fountain, trees and flowers; a large garden adjoined this filled with orange trees, banana plants and palms, with great masses of bougainvillea growing everywhere. All the rooms opened into the patio, and on one side of it there was a long, rustic dining-room.

The place looked very old-fashioned and crude, but was interesting and picturesque, and in the mild climate of Cuautla, where outdoor life is so pleasant, many luxuries indispensable elsewhere could be dispensed with. The rooms were furnished in the usual Mexican style, with tiled floors and one or two rugs, but were clean and comfortable.

The attractions of the hotel were hardly up to those of a Carlsbad establishment, for it had neither a writing nor a smoking room; but the terms were rather more attractive than the usual Carlsbad tariff, being about two dollars a day inclusive. It is true there was a good deal of Mexican about the cooking, but the meals were not at all bad and the service very fair…

It is a quaint, old-fashioned place, with narrow, cobble-paved streets, and houses of the usual low, flat-roofed type. As I strolled about the town the next morning, I noticed some unusually amusing signs of Americanization. An enterprising barber, for example, displayed a big signboard with the English inscription, “Hygienic, non-cutting barber shop,” as a tempting inducement to tourists, and one or two other establishments displayed in their windows the interesting announcement, “American spoke here.”

Carson also describes the railway station:

Cuautla is also famous for having the oldest railway station in the world, the crumbling, ancient structure which is now used for this purpose having been the Church of San Diego built in 1657. … The day after my arrival I went into the old church, the body of which is now used as a warehouse, while one side of it bordering the railway line provides accommodation for the waiting-room and various offices. A quantity of wine-barrels were piled up at the spot where the high altar had formerly stood, and all kinds of merchandise were stored in other parts of the building. Over the door was an inscription, the first words of which seem appropriate enough to the present condition of the once sacred edifice: “Terribilis est iste hic domus dei et porta coeli ” (How dreadful is this place. This is none other but the house of God and this is the gate of heaven).

In October 1973, the original narrow gauge track from Mexico City to Cuautla was replaced with standard gauge line, bringing a premature end to the lives of several steam engines. These engines were among the very last steam locomotives used in regular service anywhere in North America. Fortunately, the oldest section of narrow gauge in Mexico, built between Amecameca and Cuautla still survives. Originally built in 1881 as the Ferrocarril Morelos (Morelos Railroad) , it was partially re-opened, between Cuautla and Yecapiztla, for a tourist steam train service in July 1986, using engine #279 and four restored second class coaches. Engine 279 is a Baldwin locomotive, built in Philadelphia, first brought into service in 1904, and now spends most of its time resting contentedly in the Cuautla museum, the museum that is housed in the oldest building ever used as a railway station anywhere in the world.

What to see:

While Cuautla is probably most famous for its balneario, it is also the burial place of Emiliano Zapata, a hero of the Mexican Revolution. A bronze statue of Zapata, complete with rifle, and a sign proclaiming “Tierra y Libertad” (Land and Freedom), stands tall over the Plazuela Revolución, one block south of Cuautla’s main plaza.

On the southwest side of the plaza is the Museo Histórico del Oriente (the Casa de Morelos museum) with local history displays.

Three blocks north of the plaza is the Alameda square with various eateries and the Museo José Maria Morelos y Pavón, housed in the former railway station, with displays relating to Mexico’s early 19th century independence movement. The location of these places can be seen on the map of Cuautla on this site.

Postscript: The rival claims of Red Hall, Bourne, U.K. to be the oldest station building in the world

I am very grateful to Tony Smedley and Ian Jolly, two very alert railway enthusiasts from the U.K., for bringing to my attention the rival claims of a railway station building in Lincolnshire to be the oldest in the world. The original owner of Red Hall, in Bourne, died in 1633. The Hall was later used as the Station Master’s house and Ticket office for the Bourne & Essendine Railway, which began operations in 1860. The last passenger train through Bourne station was apparently in 1959, with freight services ending a few years later. (For more details, click on Red Hall and Bourne Railway Station respectively.

Since the Red Hall (Bourne) station no longer has any rail tracks or trains associated with it, I stand by my claim (for now at least) that Cuautla station (which does still have rail tracks and trains) is the oldest railway station in the world. However, it is clear that Carson, at the time he was writing, was sadly misinformed and unaware of the rival claims of Red Hall.

Second postscript.

Bob Katz writes, “Just to let you know that the “Did you know?” statement “The Oldest Railway Station in the World. Cuautla. Inter-Oceanic Railway.” is VERY wrong. The oldest is Manchester’s London Road station, in England. Although, it’s no longer in use on the national railway system. The oldest station, still in use, is Edge Hill station, in Liverpool. https://www.edgehillstation.co.uk/about.

TB: I am grateful to Bob for taking the time to share this and I entirely agree that Edge Hill is the earlest (first) passenger train station in the world still in use. However, the Cuautla station building (even if it was not originally built as a train station) is a far older building than the Edge Hill station building, So, while you are certainly correct that Edge Hill is the oldest station still in use in the world, I stand by my claim that Cuautla merits its status as the oldest building that is a station still in use.

For more about how Mexico’s railroads helped forge a nation, see chapter 15 in the author’s Mexican Kaleidoscope: myths, mysteries and mystique (Sombrero Books, 2016).

Sources:

- Campbell, Reau. Campbell’s New Revised Complete Guide and Descriptive Book of Mexico. Chicago. 1899.

- Carson, William English. Mexico: the wonderland of the south. 1909