Legendary Mexican artist and master muralist Diego Rivera spent so much time avidly collecting pre-Hispanic art it’s a wonder he ever got around to painting. Rivera amassed a collection of thousands of objects: pottery items, stone and jade figures of animals, gods and humans.

Many of the purchases were made on the black market. On the other hand, it is preferable that Rivera bought them than foreign collectors – since so many priceless representations of Mexico’s indigenous cultures would have vanished forever into obscure museums and anonymous living rooms; and that which was once up for grabs to the highest bidder now belongs to the Mexican people – for, before he died, Rivera bequeathed his collection to the nation. It is on display in an imposing volcanic stone labyrinth of a museum that Rivera designed himself: it is called Anahuacalli.

Anahuacalli is Nahuatl for “House of Anahuac;” Anahuac means “Valley of Mexico.” The architecture of this dramatic building incorporates features of Mixtec, Toltec, Aztec and Zapotec cultures from the Preclassic period (200-600 A.D.). It is located in the south of Mexico City, yet remains little visited by the average tourist. And while the museum and its grounds (the latter soon to be designated an ecological reserve) are well kept, the complex is located in an area where the shells of old vehicles lie abandoned on narrow streets and a neighborhood resembling a ramshackle barrio goes about its business with an air of liveliness and smalltime industry. Not exactly leafy Chapultepec Park.

Perhaps its relatively far-flung location has a tendency to discourage visitors. That is a shame, for Anahuacalli is a unique experience and, at 20 pesos for a two-hour guided tour, an inexpensive one. When Rivera built it around 50 years ago, he must have looked out across the city and feel a great love swell in his breast – for on a clear day the roof of the structure offers unrivalled vistas of the valley and the volcanoes Popocatepetl and Iztaccihuatl. One can sense something of the grandeur Rivera himself must have felt while completing this mammoth project.

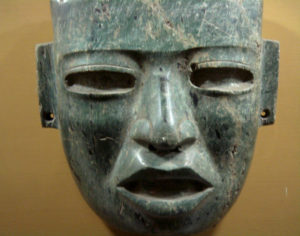

The interior of Anahuacalli is a modern Mexican labyrinth, with narrow stone staircases crisscrossing tomb-like rooms across three levels. One may encounter an ominous Totonic jaguar or an exquisitely carved armadillo. Some treasures include tiny masculine and feminine figurines, water vessels and animal carvings: more than 2,000 pre-Hispanic pieces are housed here, bathed in the changing hues of natural light.

Aside from the main attraction of the pre-Hispanic works, the second floor of the museum offers something of interest to Rivera buffs, containing a studio and works by Rivera himself. Primarily charcoal and pencil sketches, they include a number of self-portraits and studies for several of his major murals, such as El Hombre en el Cruce de los Caminos (“Mankind at the Crossroads”). Originally commissioned in 1933 for the Rockefeller Center in New York, the completed mural is on display at the Palacio de Bellas Artes in Mexico City. There is one of Rivera’s earliest surviving drawings, executed at age three, of a choo-choo train – although it hardly presages the genius that was to flower in the man. Other sketches include La Paz (“Peace”); as well as a gigantic sketch of Chairman Mao offering a peace dove to Uncle Sam. Rivera was a communist, and the theme is continued in the hammer-and sickle colored tiles that can be encountered by a keen eye from time to time on the floors of the complex.

There is a friendly, informal atmosphere at Anahuacalli. Perhaps it’s because the security staff aren’t used to large crowds here. The stillness and dignity of the museum’s atmosphere adds to one’s admiration of the contemplative nature and artistry of peoples more luridly famous for the savagery and superstition in which they conducted affairs of religion. Yet their humanity and connection to the real world shines through here.

The museum is located at Calle de Museo 150, district of Coyoacan. But that is not easy as it sounds, since it is nowhere near the touristy zone most visitors associate as Coyoacan. One must take the blue line Metro 2 to the end – Taxqueña – then the Tren Ligero another half dozen stops to Xotepingo. Alighting from this stop, one crosses Tlalpan and will see a sign indicating the direction of Museo Anahuacalli. Walk three blocks to Division del Norte, then another five up the hilly Calle Museo.

Or just take a taxi.

Upon entering Anahuacalli one may observe an inscription over the entranceway by Diego Rivera. It reads: “To return to the people the artistic inheritance I was able to redeem from their ancestors.”