Having reached Monte Alban and entered the site, on your right as you stand at the corner of the main plaza is the North Platform, the site of the Zapotec king’s residence and the temples of the nobility. Wandering around the hillside behind the North Platform, you will discover various sunken courtyards, some with vaulted tombs below. Distinguishing between residences and temples is relatively easy – the former have narrow entrances, the latter have much wider doorways.

To your left, on the eastern side of the plaza, are the distinctively-shaped ballcourt (shaped like a capital I) and The Palace, presumed home of an important dignitary. Most of the constructions you can see were built and then rebuilt several times. Also on your left, but further away, at a distance of about 300 meters, are the temples of the South Platform. Standing on the windswept South Platform, admiring the view below, leads one to ponder on the improbability of this site from the point of view of water or food supplies. Military superiority (in terms of height) it may have enjoyed, but from where did all the water and food needed to sustain this sizeable city come?

Archaeologists have worked out that the Zapotec not only engineered numerous water storages, but reorganized them as needed. Most cultivation (corn, beans, squash, chiles) took place on the valley floor; some fields were irrigated. It has been calculated that about 17,500 people could have been supported by the annual production of crops within an eight kilometer radius of Monte Alban. At its peak, the city housed twice as many – 35,000 inhabitants.

On the far side of the main plaza from the entrance, two temples, each with decorative panels, flank the Building of the Dancers. The large bas-reliefs depicting human figures in various contorted poses which can be seen in this building are one of the two particular features found in this grand plaza which deserve special mention. These strange figures were christened “danzantes” (dancers) long ago and the name has stuck, despite a total lack of evidence that they really portray performing artists.

Fifteen years ago, a local guide spent most of his two-hour personal tour trying to convince me that these bas-reliefs, of undeniably Olmec style, really represented hospital cases – they were portraits of sick people and functioned as a kind of combined medical textbook and hospital out-patients’ list. In his view, Monte Alban had been the Americas’ original General Hospital, a place of healing somewhat akin to Houston Medical Centre today! Other guides have claimed these sculpted stones show priests in various stages of ecstasy. But there is ample evidence to the contrary and the truth is almost certainly much more prosaic.

In a Scientific American article (February 1980), Joyce Marcus presents a compelling case for considering the earliest of the 300-plus ” danzantes” as pictorial messages forming an overall display, like a mural, showing captives and lists of conquered places. While the overall display must have been striking, and possibly served as propaganda, each individual monument conveyed relatively little information. On later monuments, numerous varied glyphs incorporated into the inscriptions allowed far more detailed information to be conveyed. According to Marcus, later themes included genealogical registers, diplomacy and the peaceful connection between Monte Alban and Teotihuacan. Marcus also believes that it will not be long before scholars will understand many of the details of the Zapotec hieroglyphic writing system, the oldest known in the New World, dating as far back as 600 B.C.. Just as this writing system predates both Aztec and Maya writing systems, so Zapotec calendric inscriptions also predate Maya calendar glyphs, though the two systems share the same conventions for how numbers are portrayed.

Besides the long-standing debate over the precise meaning of the ” danzantes“, the great court houses another mystery – the purpose of the enigmatic, uniquely arrow-shaped Structure J, positioned close to the South Platform. Of all the structures found at Monte Alban, this is the most puzzling. A brilliant, but unsubstantiated, early guess by famed Mexican archaeologist Alfonso Caso in the 1930s that it was an astronomical observatory has gained considerable strength in recent years as a result of the pioneering work of archaeoastronomer Anthony Aveni.

Aveni has shown how the building’s front doorway is precisely aligned with the point where the bright star Capella (the sixth brightest in the sky) would have first appeared in the dawn sky each year, on precisely the same day that the sun reached its first of two annual zenith days over Monte Alban, on each of which it casts no shadow at mid-day. The front stairway of J is aligned in turn with Structure P (on the eastern side of the plaza), which has a unique vertical shaft leading down into a chamber down which the sun would have shone with no shadow on that same day. Crossed-stick symbols found on Structure J lend further support to the importance of astronomical sighting-stick observations from this position. Moreover, the asymmetric plan of Structure J turns out to be precisely aligned with the point to the west where 5 of the 25 brightest stars in the sky, including the Southern Cross, first rise above the horizon. Proof positive, this isn’t, but suggestive, it certainly is.

The invisible mystery of Monte Alban is how the most enduring of all the Classic civilizations of Mexico (lasting from about 500 B.C. to 800 AD) could rapidly collapse in a heap. What could possibly have provoked the city’s disintegration and demise? As with similar collapses of pre-Columbian cities elsewhere in Mexico at about the same time, theories range from the collapse of the economic system involving the payment of tributes, to political unrest, climatic change, large-scale epidemics and soil exhaustion. Whatever the cause, Monte Alban declined and Mixtec Indians displaced the Zapotecs, pushing them to the east where, before long, smaller city states, such as Mitla, were springing up on the valley floor.

In Monte Alban, the Mixtecs did little more than occupy existing buildings, and utilize existing tombs for burying (or reburying) their ancestors. One such tomb, known simply as Tomb 7, was excavated in 1932, during Alfonso Caso’s very first season of work on this site. The spectacular contents of this tomb – including gold items with a combined weight of 3.6 kilos – are now on show in the Regional Museum in Oaxaca city. If you only have time to see a single thing in the city, then make sure that this is it!

While you wander around Monte Alban, it is quite likely that someone will shyly offer you “genuine pieces of Zapotec art”. You can rest assured that such pieces may be genuine, but they are certainly not old! Years ago, I was the last person to leave the site one afternoon as it closed. Driving back down towards the city, I passed a young boy, about seven years old, walking down the hill with his sister. With a dark sky threatening an unseasonal downpour, I offered them a ride. No sooner were they seated in the car than the boy began to extol the virtues of the “genuine pieces” he carried wrapped in a dirty old rag. A few minutes later, expressing my interest in his “highly desirable antiquities”, I asked him about the deities they represented and was obviously gaining his confidence. When I slipped in a question about when they had been made, his pride shone through as he swiftly, and unthinkingly, replied, “Why, señor, in 1979!”

From Monte Alban, it is only a short drive through the gently rolling Zimatlan valley to Cuilapan and Zaachila. The huge ex-monastery of Santiago Cuilapan, the largest in the region, is a national treasure and easily visible to the right of the highway.

As you walk towards the monastery, your eye is drawn not to the massive walls of the main building but to the extraordinarily evocative unroofed Basilica to the left. A long narrow nave is flanked by graceful arcades of beautifully-proportioned arches. Either side of its main entrance are curious circular towers, built of locally-quarried limestone blocks, with conical turrets that, in the words of colonial religious art specialist Richard Perry “might have graced a medieval French chateau”. The Basilica served as the monastic church for many years; after it was abandoned a century ago, its wooden roof was destroyed in a fire.

There is something about ruins and partially finished buildings that speaks to the soul. Certainly, the monastery of Cuilapan speaks reams of colonial history. From the monastery’s beginnings in the middle of the sixteenth century, plans for its completion were constantly delayed, in response to the vicissitudes of the time. Neither the monastery nor the church were ever completed. Hernán Cortés, who had claimed most of the Valley of Oaxaca for himself, had little desire to cede control of even this small part of his domain to the Dominican order. Funds were hard to find. Labor was in short supply. Officials in Mexico City and Spain considered the project overly ambitious.

But the parts that were built are impressive. Constructed to withstand the earthquakes to which this area is prone, the walls of the monastery and church are as much as three meters thick in places. Set into the floor of the unfinished church is the tomb of Princess Donaji, a Zapotec princess and early convert to Christianity who fell in love with a Mixtec Lord, the Lord of Tilantongo (a town north-west of Oaxaca).

The feast day of Santiago Cuilapan (Saint James Cuilapan) is celebrated on July 25 each year. The Dance of the Conquest, a reenactment of Cortés’ defeat of the Aztecs, is presented by plumed dancers wearing spectacular oversized disc-shaped headdresses. The dance, performed in the atrium of the monastery, has roots extending back to the annual commemoration by the Mixtec people here in Cuilapan of an ancient victory they had achieved over their Zapotec rivals. At the time of the Conquest, Cuilapan was a Mixtec enclave in otherwise Zapotec territory.

Inside the monastery (an admission fee is charged), some parts of the interior are slightly spooky. Indeed, on a quiet day you may be the only person wandering the corridors. But you are not really on your own. Apart from the custodian and a small group of art restorers working on the upper floor, the spirits of the past accompany you. Near the entrance is the cramped cell where Mexico’s second president, Vicente Guerrero, was held prisoner for 48 hours in February 1831 prior to his execution. In his honor, the formal name of the town became “Cuilapan de Guerrero”. Close to the main stairway is a mural, “The Tree of Friars”, depicting branches spreading out from St. Dominic, founder of the Dominican order. On each branch are rows of saints and martyrs, some clutching their own severed heads. Upstairs, from the second floor, you have a commanding view over the surrounding countryside back towards Monte Alban.

From Cuilapan, it is but a few minutes drive to Zaachila. On a Thursday, this part of the trip is worth doing first, early in the day, since Thursday is Zaachila’s weekly market day. If you start at Zaachila, return to Oaxaca via Cuilapan and try to include the next stop, Arrazola, before spending the afternoon at Monte Alban.

When the Spaniards first arrived, Zaachila was a town of Zapotec-speaking Indians ruled by an elite Mixtec minority. Zaachila had previously functioned as the Zapotec capital. Today, there is little to see except for a black Christ in the main church and a pair of Mixtec tombs excavated in the side of the hill to the north of the church. A steep staircase descends to Tomb 1 with its stucco decorations depicting owls and cat-motifs and bas-reliefs of a person whose torso is covered with a turtle shell and another figure whose head is shown emerging from a serpent. Do not rely on the Tomb always being open for inspection, however.

Thursday mornings is when Zaachila’s market square comes alive, but things grind to a halt by midday. In the hot afternoon sun sleepy dogs warily scrounge whatever scraps of leftover food they can find from among the debris left behind after the morning market.

After Zaachila, it’s time to return towards Oaxaca, but it’s well worth making one short detour on the way back. To get a taste of the well hidden handicraft surprises that intrepid travellers can find in many of the small villages of the region, take the side-road to Arrazola. Though not well signed, Arrazola is only a few kilometers off the main Oaxaca-Zaachila road. The road passes several tiny hamlets before climbing slightly to end at Arrazola’s small, remodelled plaza.

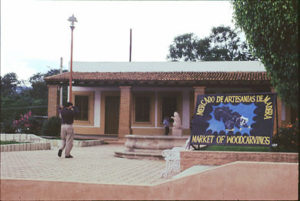

On the plaza is a village co-operative store selling examples of Arrazola’s finest art – hand-carved, brightly painted, very distinctive wooden animal figures. The store may be closed, but any small child will eagerly lead you through the dusty streets to his or her family’s workshop where you can watch the animals being made.

The wooden animal craze was begun by one Manuel Jimenez some thirty years ago and has taken the whole village by storm. Every family, it seems, has its own workshop, competing for the most fanciful designs. Once the basic form has been decided, strongly contrasting colors of paint are applied, often in dozens of tiny dots, to finish these whimsical figures. Expect to pay anything from a few dollars for an easy-to-pack unsigned piece to several hundred dollars for a large, signed masterpiece.

Bargaining is de rigueur, but don’t expect to persuade the artisans that the price already marked on the piece you like is way out of line – they’ve been surreptitiously watching your eyes dance over their display and recognize genuine interest when they see it, even if only caught out of the corner of their eye! And don’t doubt the sharpness of their eyesight – it is clearly and beautifully proven by the exquisitely detailed figures and animals they so painstakingly carve and color.

How to get to Cuilapan, Zaachila and Arrazola.

These villages are difficult to reach by public transport without wasting a lot of time waiting for the next bus to arrive. If you are unable to find a tour taking in all three places, then consider either hiring a car for the day (and driving yourself) or bartering with a taxi driver for a three hour excursion. From Monte Alban, return towards the Atoyac bridge, but before crossing the bridge, veer right (south) on the Zaachila road. Cuilapan is about ten kilometers south of Oaxaca on this road and Zaachila is six kilometers beyond Cuilapan. To visit Arrazola, retrace your steps back towards Oaxaca city; about eight kilometers south of the Atoyac bridge, turn left (west). This road ends at Arrazola.

Detailed map of places mentioned in this article