(The following account represents my personal feelings and subjective impressions as I experienced Semana Santa last year. Since I am neither Catholic nor Mexican, I don’t fully understand all the religious significance of the processions and pageantry. Although Holy Week is celebrated throughout Mexico, the colonial mountain town of San Miguel de Allende is famous for its Semana Santa celebrations and attracts visitors from around the world. These happenings, however, are not staged-for-tourists events, but are centuries-old traditions that have caught the imagination of travelers.)

Semana Santa, or Holy Week, is a misnomer. It’s NOT one week! It’s TWO full weeks of parades, processions, parties, prayers and pageantry. For me, it started at 3 a.m. March 16, 1997–two Sundays before Easter. Fireworks. Loud booms. Without a pause. That’s why I remember the exact hour.

Since middle-of-the-night fireworks are common in Mexico, I merely turned on the light and began reading. I keep a book bedside for this purpose. I knew the party would end in an hour or so, and I could go back to sleep. But…this party didn’t stop.

EL SENOR DE LA COLUMNA

At about 6 a.m., a bunch of us gathered on the rooftop of the bed and breakfast where I was staying. Bands were playing in the streets below, and we saw hordes of people in a square a few blocks away.

What I didn’t know then, but learned later, was that hundreds of Mexicans and a smattering of U.S. expatriates had walked from the historic town of Atotonilco, four miles away. Men carried a casson bearing one of the area’s most beloved statues — El Señor de la Columna. This lifesize replica of a bleeding Jesus tied to a column, wore a purple velvet cape, protected by a pile of silk scarves. As the early morning sky turned slowly pink, the men began removing the scarves, These silk pieces, recovered by their owners, will be used in funerals and other ceremonies during the coming year.

After a prayerful mass in this square, the statue continued it’s journey to the nearby bright white stucco church of San Juan de Dios. For the next two weeks, amidst fireworks and gala processions, the dramatic Christ would be carried to other churches, and then back to its Semana Santa home at San Juan de Dios. Then, on the Wednesday after Holy Week, marchers and fireworks, and bands would again accompany El Señor de la Columna to its permanent home in Atotonilco.

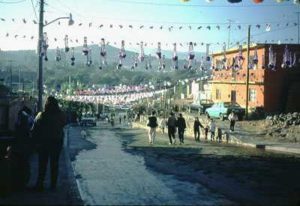

After breakfast, I walked along the road toward Atotonilco. Each home, whether a two-story stucco or a tin-roofed shack, was decorated with paper flowers. They were predominately white and purple, made from toilet tissue and colored crepe paper. The paper flowers, along with balloons and plastic banners of intricately cut designs, also hung from wires that spanned from one side of the wide street to the other.

By the time I walked along this roadway, the marchers were gone. and aged, wrinkled-skinned women were sweeping the cuttings of wildflowers, herbs, and palm fronds strewn in the street for the marchers. I imagined that while some families in this area spent the night decorating their homes and streets, others had been busy setting off fireworks.

FIRST DAY OF SPRING

It doesn’t always happen, but as an added bonus, last year the first day of spring arrived during Semana Santa. Traditionally, in San Miguel de Allende on this day, children from about 5 years to 8 or 10 years, dress up as bumblebees, butterflies, daffodill, tulips and Walt Disney characters. For hours, teachers march proudly alongside their costumed students as they parade around the central jardin. A tiny king and queen waved constantly from a flowered float, complete with petite princes and princesses dressed in white satin and sequined silver.

Watching this parade, I thought to myself, ‘This is a dress rehearsal. This is practice time for these niños, who one day might very well become centurions astride live horses in the Good Friday pageantry.’

VIRGIN DE DOLORES – THE VIRGIN OF SORROWS

The Friday preceding Holy Week is dedicated to the Virgin of Sorrows. Coincidentally, last year this was March 21, the first day of spring. Throughout the town, altars sprung up overnight. Vendors, in mule-drawn wagons, ladened with clumps of wheat, wove through the town selling their wares. These tiny sheaves of grain, combined with bitter oranges, gold foil, and picutres of the Virgin of Sorrows decorated altars in windows and doorways of homes, in courtyards of businesses, and in gardens of guesthouses.

The bitter oranges symbolize the Virgin’s sufferings, gold foil symbolizes the highest purity, and the sprouting wheat represents ressurrection and renewal of life. Some of the displays were impressive works of art; others simple in their construction. From all emanated deep feelings of sorrow and hope.

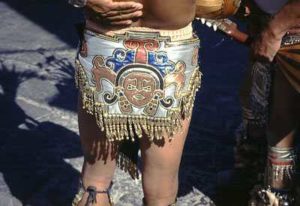

THE CONCHEROS

Periodically, and without any notice or regularity that I could discern, the concheros dance group paraded and danced around the jardin. To the steady beat of drums, flute-like instruments, and jangling ankle bracelets made of nuts, these colorfully costumed indigenous dancers entertained for hours in the streets surrounding the jardin.

Although these ritualistic dances sprung up after the Spanish conquest, they incorporate many pre-Columbian religious symbols. A cynical part of me suspects these dances and elaborate outfits are underwritten by Kodak or Fujii. Who could resist buying an extra roll of film to photograph the costumes of leather, satin, feathers, jewels, sequins? Besides, these garments flimsily adorned ever-so-photogenic, muscular, bronzed bodies. More than once, my daily itinerary was interrupted and changed by the chanting and stomping of these dance group members, some of whom live in San Miguel and some who come in from the neighboring city of Queretaro.

ST. PATRICK’S DAY

In 1997, St. Patrick’s Day fell within the two-week Holy Week celebrations. St. Pat in Mexico? Yep. There was a night-before, Celtic musical show in the jardin, followed by an 8 a.m.. wearing-of-the-green parade. Of course, St. Patrick was a Catholic, but deep down I believe the Mexicans’ love of parades underlies these celebrations.

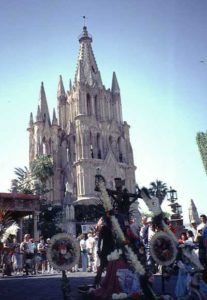

PALM SUNDAY

On this day, pageantry and a Catholic mass in the parroquoia (the beautiful church in the main square) is backdropped by children and indigenous people selling flowers, palms, handwoven wall hangings made from palm fronds. By this day, the town is overflowing with visitors. San Miguel de Allende is a particularly favorite destination for people from Mexico City during this time.

GOOD FRIDAY

If you have only one day during Semana Santa to be in San Miguel, mark Good Friday on your calendar. I can’t imagine another day–anywhere– that can match this one in sheer emotion and pagentry. There are processions organized by almost every church in town. I accidentally, and luckily, got caught up in the procession of the El Senor de la Columna as it went from the San Juan de Dios church to the Parroquia, the church which anchors the jardin. Leading the procession were niños dressed as disciples, and Roman centurions.

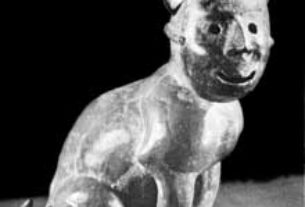

Figures of San Roque, complete with ulcerated leg and his faithful dog, lead the procession, A favorite legend surrounds San Roque, who, dying with an ulcerated leg, was saved by his dog, who fetched bolillos (rolls) and fed them to his master.

The jardin, with rows of people, ten deep, is the place to be midday on Good Friday. It has all the makings of a Hollywood movie, except the actors are real, fervent in their beliefs, and aren’t being paid. San Miguel’s Good Friday pageant has been filmed and is being filmed as I watch it. However, what makes it a best seller, is the deep emotions and sincerity of the players.

Centurions in full Roman garb head the parade riding real horses along the square’s narrow streets. Bigger than lifesize statutes of St. John, the Virgin Mary, Mary Magelene, Judas, and John the Baptist stand on weighty platforms, carried by strong Mexican men. Perspiration drips from their brows, from the load they carry on their shoulders. During the hours-long parade, men took turns carrying the floats.

Blood drips from the real crown of thorns on the brow of the real-life person portraying Jesus. He drags a heavy cross behind him. The procession winds its way around the jardin. Spectators — Jews, Muslims, Hindus, Catholics, Protestants, gnostics, athiests and others — watch the re-enactment of Jesus’ last hours.

A woman next to me whispers, “Did you see that? Mary nodded.She really did!” I learned later that a highlight of this mid-day Good Friday theater is the huge statue of Mary, who, facing her son for the last time, nods, as told in the scriptures.

As impressive and unforgettable as the pre-crucifixion pageantry was, the near-dark Good Friday procession in San Miguel de Allende will remain with me forever. After an afternoon of silence (except for some tourist joints which had live music), the town once again filled with an awesome procession. Everyone in this parade, with no exceptions, was dressed in black. The center stage players of the earlier parade, i.e., statues of Mary, St John, etc., were there, draped in black. Hundreds (thousands?) of black-garbed marchers slowly walked through the streets to the mournful sounds of hollow drumbeats.

Drawn by the emotions of the moment, I joined in the parade. Trapped in a sea of people, I walked toward the Church of the Oratorio, unable to get out of the dense jungle of mourners. Prepared to participate in an hour-long Catholic mass, I had no choice but to continue toward the church’s entrance. At the last moment, an escape route opened up, and I, toghether with hundreds of others, walked back toward the jardin.

Literally, hundreds of spectactors watched or joined this procession. Faces were somber, or streaked with tears. Even rabble-rousing tourists were mute, moved by the black procession.

FIRING OF THE JUDASES ON EASTER SUNDAY

If you shoved me into a corner and asked my favorite happening, I’d have to say, “Firing of the Judases.” In San Miguel, this happens at 1 p.m. on Easter Sunday. There’s no parade this day, for the first time in two weeks. There’s no showing off of Easter bonnets and finery, no colored egg hunt for the niños. Families attend mass and in-home festivities.

However, in the jardin there’s the Firing of the Judases. (Note: Traditionally, this was on Saturday but has been changed to Sunday.) Eight ropes are strung from trees in the jardin to balconies on the government buildings, across Calle de Canal. This includes the building that houses the Police Department.

From these ropes, hang bigger-than-lifesize papier mache replicas of hated people. Some of the political figures, of course, I didn’t recognize. Some, I did, such as ex-president Salinas.

Even though the firing (or in some cases, burning) of the Judas dolls has biblical roots, this flight of fancy event as it is now staged in San Miguel de Allende , seems blatantly aimed at tourists. Construction of the large people is underwritten by hotels and restaurants, who paint their name on the figures.

All of the Judases were men, except for two — one a wicked witch dressed in black and one a colorful Superwoman garbed in yellows and blues. The waist of these figures held a round of fireworks, which, when triggered, sent off a sputtering of firecrackers, ending with a tremendous and powerful bang!

During this final boom, the figures explode, sending bits and pieces onto the street below. Children then scurried to retrieve an ankle, a neck, or a wrist. As I watched this fun, I thought to myself, “how cathartic to blow up your enemy (made of papier mache).”

In addition to the main happenings in the jardin and parroquia, there were dozens of small parades and sidewalk celebrations in front of neighborhood churches scattered throughout the town. Its impossible to walk around on any given day without coming upon a procession or celebration.

From the fireworks announcing the arrival of El Señor de la Columna to the whimiscal Firing of the Judases, Semana Santa in San Miguel de Allende rates high in my travel memory bank. If you go there, or anywhere in Mexico during the two weeks before Easter, try to put aside your personal religious beliefs and absorb the emotions of the moment.

They are real.