Mexican History

When does a tradition cease to be a tradition? Conversely, at what point in time and under what circumstances does a tradition begin? “Tradition” may be defined as “a statement, belief, or practice transmitted (especially orally) from one generation to another.”In general a “tradition” lasts a long time, but all traditions have to begin some time, somewhere. There are perhaps two ways of looking at Indian tribal art in general: traditional and generic. Traditionally, patterns and methods are handed down from parents to children but the particular stylistic expression may change over time with the introduction of new materials and changing concepts. In this sense there is no “traditional” Indian art. Generically, however, the altered or new form of the art is still part of the tradition. Once a tradition ceases to adapt to changing conditions it becomes a mere museum exhibit.

Traditional art among many North American Indian tribes was influenced both by the environment and the materials available to the artist. Among eastern and northern woodland Indians, floral designs copied from the natural sylvan surroundings prevailed. Among the plains Indians, geometric patterns reflected more accurately the generally flat terrain of the Great Plains. Before the arrival of the European traders, the woodland peoples in particular used dyed porcupine quills to weave intricate designs on tobacco pouches, headbands, and baskets. When traders introduced the small Italian-manufactured coloured glass beads, native artists quickly adapted to the new medim and continued to produce increasingly elaborate variations of the original decorative designs and religious symbolism. The use of commercial or manufactured products, such as glass beads, in place of porcupine quills or other strictly indigenous materials, does not thereby nullify the authenticity of the artistic production. Few people would argue that Indian beadwork is not authentic simply because it is made of imported European trade goods.

The authenticity of Huichol art on the market today becomes of some importance when called into question by no less an authority on the Indians of Mexico than the famous Mexican historian and anthropologist Fernando Benítez, who once described the popular Huichol yarn paintings as “…a falsification and an industry.” Benítez was referring to one of the original yarn paintings which depicted the spirits or souls of deceased persons as disembodied floating heads. He argued that the Huichol did not traditionally represent the dead in this manner and that the whole concept smacked rather of a Walt Disney fantasy than authentic Huichol religious art. The Huichol, of course, have an entirely different concept of the meaning and purpose of their art.

There is always more than one side to every story, and the history of Huichol art is no exception. In the 1960s, a Huichol by the name of Ramón Medina Silva was living in what was then the outskirts of Guadalajara. Padre Ernesto Loera Ochoa, a Franciscan priest sympathetic to Huichol culture, founded a Huichol museum at the Basilica of Zapopan in the northern part of Guadalajara. Father Ochoa bought Ramón’s artwork and encouraged the production and sale of Huichol art. Then Peter Furst, an American anthropologist, suggested to Ramón that he represent the traditions and beliefs of his people by pressing coloured yarn into a wax-covered baseboard to form designs. Beginning with the nearika (also spelled neali’ka or nierika), a traditional Huichol representation of the deified face of the sun, the Giver of Life, Ramón began to produce these yarn paintings. About twenty of them were put on display at the Casa de Cultura in Guadalajara. Soon copies and imitations of the originals began to appear. I have several in my own collection. In the intervening years, more Huichol artisans took up the challenge. The designs became increasingly elaborate and colourful while retaining much of their symbolic religious meaning.

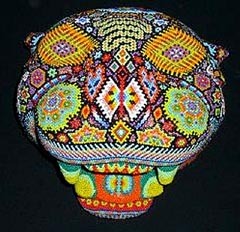

There is always more than one side to every story, and the history of Huichol art is no exception. In the 1960s, a Huichol by the name of Ramón Medina Silva was living in what was then the outskirts of Guadalajara. Padre Ernesto Loera Ochoa, a Franciscan priest sympathetic to Huichol culture, founded a Huichol museum at the Basilica of Zapopan in the northern part of Guadalajara. Father Ochoa bought Ramón’s artwork and encouraged the production and sale of Huichol art. Then Peter Furst, an American anthropologist, suggested to Ramón that he represent the traditions and beliefs of his people by pressing coloured yarn into a wax-covered baseboard to form designs. Beginning with the nearika (also spelled neali’ka or nierika), a traditional Huichol representation of the deified face of the sun, the Giver of Life, Ramón began to produce these yarn paintings. About twenty of them were put on display at the Casa de Cultura in Guadalajara. Soon copies and imitations of the originals began to appear. I have several in my own collection. In the intervening years, more Huichol artisans took up the challenge. The designs became increasingly elaborate and colourful while retaining much of their symbolic religious meaning.Like their North American Indian counterparts, Huichol artisans began to use commercial or store-bought materials, when available, to produce their art. More recently, some Huichols have begun using beads in place of yarn. Moreover, the idea of yarn painting has expanded to include large beaded figures, such as jaguar heads, masks of the sun and moon, and various animal forms. Is this “authentic” Huichol art? Perhaps in the end it depends mainly on your point of view. When I was a boy, I made Sioux Indian war bonnets out of genuine eagle feathers using traditional materials in the traditional way just as a Sioux warrior would have done. In fact, I was a Sioux warrior, in my imagination at least. Some years later at the Calgary Stampede, I saw a real Sioux Indian with a war bonnet made of white turkey feathers with the fluffy down feathers died blue. I decided that if a real Indian chief could make do with turkey feathers instead of the traditional Golden Eagle feathers, I could do the same. So I made one exactly the same and still have it today. Are my war bonnets less “real” or “authentic” because I made them? I have seen Indians from woodland tribes which had no connection whatsoever with the plains Indians or the tradition of the feathered war bonnet wearing commercial-looking war bonnets at ceremonies, because that is what the whites expected of them. Is a work of art authentic or real because of the person who made it or because of the spirit with which it is imbued?

So too for Huichol art

Thanks to the Norwegian explorer and ethnographer, Carl Lumholtz, we know a great deal about traditional Huichol art. Lumholtz spent a total of five years between 1890 and 1898 in northwestern Mexico recording, among other things, the material culture of the Huichols, especially their traditional religious art forms. A complete survey of the symbolic and decorative art of the Huichol is beyond the scope of this present article. However, it included woven belts, sashes, side bags, nearikas (originally small square or round tablets, usually made of native wool), masks (for magical purposes or to frighten enemies in battle), arrows (as prayer offerings of different types), prayer bowls (to catch the blood of animal sacrifices), sombreros (different designs and purposes), and even sculpture (stone carvings in sacred caves and statues of the deity Nakawe), to name only a few items.

Thanks to the Norwegian explorer and ethnographer, Carl Lumholtz, we know a great deal about traditional Huichol art. Lumholtz spent a total of five years between 1890 and 1898 in northwestern Mexico recording, among other things, the material culture of the Huichols, especially their traditional religious art forms. A complete survey of the symbolic and decorative art of the Huichol is beyond the scope of this present article. However, it included woven belts, sashes, side bags, nearikas (originally small square or round tablets, usually made of native wool), masks (for magical purposes or to frighten enemies in battle), arrows (as prayer offerings of different types), prayer bowls (to catch the blood of animal sacrifices), sombreros (different designs and purposes), and even sculpture (stone carvings in sacred caves and statues of the deity Nakawe), to name only a few items.Originally most, if not all, Huichol designs had a particular religious or symbolic meaning. Plant and animal motifs are still common. The toto, a small five-petalled white flower that grows in the rainy season, is worked into embroidered patterns with different petals, according to the taste of the individual artist. Designs on sashes and belts imitate the variegated markings on the backs of real snakes, which the Huichol associate with rain, good crops, health, and long life. A scorpion pattern may be used as a charm against the bite of the venomous creature. Like their predecessors, the classical Aztecs, the Huichol still have an extensive pantheon of deities. Takutzi Nakawe, the ancient goddess, mother of all the gods, creatress and destroyer of all that exists, is represented in religious art, such as statues or yarn paintings. Today even the most decorative designs usually retain a certain religious or symbolic meaning.

One of my yarn paintings is by my friend Ignacio Montoya (“Nacho” — Huichols seldom divulge their Indian names to outsiders), a marakame (shaman-priest) from Las Guayabas in the Huichol Sierra. Here is how he interpreted it for me. In the centre is Tau, the deified face of the Sun, Giver of Life. Various symbolic designs are woven in around the edges of the sun’s rays, such as peyote flowers and buds, stalks of maize, lizard, deer, scorpion, and offerings of prayer arrows. Lizards with flowers on their backs eat the peyote flowers but they are also the guardians of the peyote, the Dios Hikuri, or Peyote God. At the bottom of the yarn painting reclines the human-like figure of Nakawe, the Goddess or Mistress of the Rain. The entire scene represents Wirikuta, where the Indians go each year to gather the peyote they use in their ceremonies. The symbols are traditional and represent the religious beliefs and customs of the Huichol. The design, however, is Nacho’s own artistic creation and is based on a dream he had about Wirikuta, the sacred land of peyote in the desert of San Luis Potosí.

Contrary to dire predictions, the Huichol are not dying out, at least not yet. Their evolving art forms bear witness to the resilient nature of the people. Every art form has its own intrinsic aesthetic value but may also represent a common thread of meaning running through all cultures. Traditional Huichol art reveals some of these connections and opens a window on the past which enables us to see not only where we have been but where we are now and may be in what we choose to call the future. Science notwithstanding, there is more than one “reality” in the world. What we commonly call mythology is really someone else’s religion. The Huichol belief in spirits and supernatural realms, which we tend to regard as mere superstition, may in fact reflect the true state of our inner minds. The Huichol are attempting to survive in today’s impersonal market economy by commercializing their art. But while money is important to the Huichol, as it is to most of us, it is the spirit of the artwork that ultimately counts, not its monetary value.

- Huichol art, a matter of survival II: authenticity and commercialization

- Huichol art, a matter of survival III: motifs and symbolism

- Huichol art, a matter of survival IV: an art in evolution