Did You Know…?

Prior to the founding of San Juan de Carapoa (later renamed El Fuerte de Montesclaros) by Francisco de Ibarra in 1564, relatively little is known of the early Indian peoples living in the Fuerte valley. They probably harvested wild plants, farmed small gardens, fished and hunted for their survival. They appear to have had few links to other tribes outside the region.

By the end of 1530, an exploratory group of Spaniards, led by Nuño Beltran de Guzmán (the founder of Guadalajara), had reached the area south of Mazatlán but had not ventured much further north. In the following years, Beltran de Guzmán organized follow-up expeditions. As far as we know, the first white man to set foot on the shores of the El Fuerte river (then known as the Zuaque) was his nephew—Diego de Guzmán—in September 1533. The river was so close to overflowing that it put a temporary halt to their plans to continue any further north. A year earlier, a ship sent by Hernán Cortés (in an effort to leapfrog his dominions over and beyond those of Guzmán) had been wrecked in a storm off the Sinaloan coast and the entire crew killed by Indians.

An amazing journey and astonishing encounter

One of the most remarkable encounters in history took place just 20 kilometers from El Fuerte, in 1536. The Spaniards found four survivors of a much earlier expedition which had set sail from Cuba and been shipwrecked off the coast – of Florida! Alvaro Nuñez Cabeza de Vaca, Alonso del Castillo Maldonado, Andrés Dorantes de Carranza and a black slave named Estebanico, had spent 18 years traversing on foot through what today are the states of Alabama, Louisiana, Texas, New Mexico, Chihuahua, Sonora and Sinaloa. In Sonora, they saw a Yaqui Indian who had, etched on his collar, the clasp of a sword. Realizing that they must finally be close to other white men, they set a forced march until they met up with four Spaniards on horseback, near what is today the Los Ojitos ranch.

The Seven Cities of Gold

From the Indians he had encountered, Cabeza de Vaca had heard plenty of rumors of a large province to the north called Cíbola, said to have seven walled cities with large houses and lots of gold and silver. Another rich kingdom, Quivira, was supposed to be nearby. The first organized attempt to prove that Cíbola really existed was made by Fray Marcos de Niza, with Estebanico as guide. Reaching Arizona and the lands of the Pueblo Indians, Estebanico was killed. Unwilling to admit defeat, Marcos de Niza returned with exaggerated tales of what he had seen and heard. As a result, in 1540, a second expedition was organized, this time led by the redoubtable Francisco Vázquez de Coronado. Coronado’s expedition, with 250 horsemen, 60 soldiers and 1000 Indians, traveled way north, finding the Grand Canyon (Pedro de Tovar being credited with its “discovery”), as far as the 40th parallel and the Arkansas river. Finding nowhere that matched the lyrical descriptions of Cíbola and Quivira, Coronado returned to the Viceroy in 1542 and the Seven Cities of Gold became yet another of the many fabulous myths associated with the Spanish quest for New World riches.

El Fuerte de Montesclaros

Shortly after the founding of San Juan de Carapoa in 1564, it was destroyed by Mayo Indians. A Jesuit mission was established here in 1590. Following repeated Indian uprisings and the martyrdom of a Jesuit priest named Gonzalo de Tapía, a rectangular, adobe-walled Fort (hence the town’s new name of El Fuerte) was built between 1608 and 1610 by Capt. Diego Martínez de Hurdaide to prevent further Indian uprisings. The fort, roughly 100 meters by 100 meters, and criticized at the time as being far too expensive, became a frontier post, controlling the routes into Indian territory much farther north. The town subsequently became a trading post (gold and silver-mining) and for almost three centuries was the most important commercial center of a vast frontier area: north-western Mexico.

Every one of the expeditions to colonize Arizona and California passed through El Fuerte and even in the 1848 California gold-rush, many of those seeking their fortune originated here – so many went north that the region suffered a marked drop in population. The rush north was offset somewhat by mineral discoveries closer to home and in the Copper Canyon region.

Capital of the Western State, including Arizona

In the nineteenth century, El Fuerte was (briefly, from 1824 to 1826) the capital of the Western State, the interim state of Sinaloa-Sonora (which included part of Arizona, stretching as far north as the Grand Canyon). The capital was then moved to Alamos, before moving to Copala. The Western State was subsequently divided and two new states – Sonora and Sinaloa – became independent in 1831. Indian conflicts (eg the Yaqui war) smoldered on until 1936. The name Sinaloa, incidentally, is thought to derive from cinaro (pitaya or cactus).

While nothing is left of the original fort, El Fuerte town today has a pleasant, partially restored center with typical provincial colonial-style buildings. The town (population about 30,000; altitude about 190 meters) is proud of its traditional Sinaloan culture. Brass and drum bands play tamboras sinaloenses, a German-Mexican musical blend peculiar to Sinaloa. Evening activities focus on the shady plaza.

Just off the main plaza, on the slopes of the hill where the fort was originally (nothing visible remains today), construction began in 1903 of the Almada mansion, now the Posada Hidalgo hotel. Rafael Almada, who later became the Mayor of El Fuerte, was born in Alamos in 1861 and married his cousin, Rafaela, there in 1897. Two years later, they moved to El Fuerte and set up a trading business. In the style of the times, whenever Rafaela went to church, she insisted on being taken in her four-wheeled carriage (calash) rather than walking! The Almadas spent 5 years and 100,000 gold pesos on constructing their mansion, though Rafael died suddenly, barely two years after its completion. His funeral carriage can still be seen in the hotel. The wooden trim, 285 pine beams and much of its lavish antique furniture were brought by boat from San Francisco and unloaded at Topolobampo during the time of Albert K. Owen’s colony. Ironwork was brought from Mazatlán. In its heyday, Almada’s house was the finest building in the town. In 1913, for example, Venustiano Carranza (later president of Mexico) stayed here. President Carlos Salinas de Gortari also stayed here, in May 1991, but that’s another story… It is worth exploring the recesses of this hotel since in some respects it is a living museum with entrance mural, antique furniture, sepia photographs and aging mementos of earlier decades.

According to some, the spirit and ghost of Rafael Almada live on in the hotel, so be prepared for strange noises in the night and for the ancient pianola sometimes bursting into tune all by itself. Equally, it used to be said that vast quantities of gold and silver lay buried under the floors and in the garden, but you can probably rest assured that any such treasure was dug up and invested elsewhere when Almada’s mansion was extensively remodeled into the present hotel.

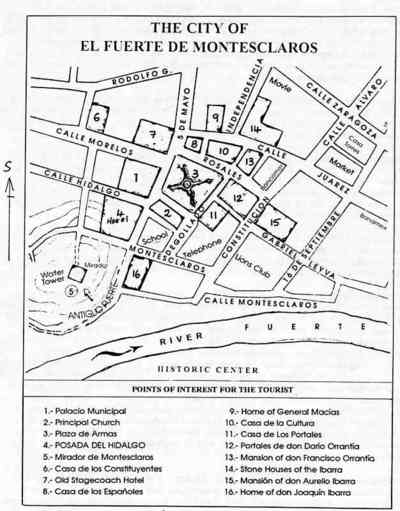

El Fuerte is a pleasant town to stroll around. Narrow streets, many lined by fine stone buildings, converge on the plaza. The church (with the tomb of Esteban Nicolás de la Vega y Colón de Portugal, the man who singlehandedly paid for its entire construction) is reputedly eighteenth century but many townhouses are likely to be considerably older. For example, Casa de los Alvarez (Constitución, almost on the corner with Juárez) has walls over a meter thick! Casa de los Constituyentes (# 6 on map) is also very old; this was the first House of Congress for the Western State. The rear part (on Constitución) of Casa de los Portales (# 11 on map) is old but the front, on the plaza, has been remodeled. # 10 on the map is the former Casa de la Bóveda, and former jail, now the Casa de la Cultura. Next to the Mansión de don Aurelio Ibarra (# 15) is don Aurelio’s old, two-storey mercantile building, built at the end of the last century. The interior courtyard of the municipal palace (1903-1907) is out of all proportion, designed apparently for a much larger town, and built when Rafael Almada was Mayor and Political Prefect of the district. Most commercial activity is not on the plaza but down the side streets. As for cuisine, El Fuerte is famous for fresh largemouth bass (from nearby reservoirs) and for agua de cebada, a mixture of barley, sugar, cinnamon and vanilla.

Even after its heyday at the turn of the century, El Fuerte still had an important part to play in national (revolutionary) history. In November 1915, in the middle of the Mexican Revolution, Carranza fought and defeated the legendary Pancho Villa here — the defeat marked the beginning of the end for Villa’s División del Norte.

From El Fuerte, side-trips can be arranged to visit the Máscara mountains with their petroglyphs (a short hike on the other side of the Fuerte river), Isla de los Pájaros (Bird Island), and to Mayo Indian missions like Tehueco (Blue Sky), founded in 1648 and Baymena. Another Indian village, noteworthy for its rustic earthenware pots and pans, is Capomos. An unpaved secondary road, formerly a stagecoach route, links El Fuerte to another former mining town, Alamos (90 kilometers away; allow 3 hours) which in recent years has become a popular destination for Americans and Canadians. Many restored stone mansions have been turned into small hotels and bed and breakfast establishments.

This article is the basis for Chapter 11 in the author’s Mexican Kaleidoscope: myths, mysteries and mystique (Sombrero Books, 2016).

Source:

- “El Fuerte en la Historia” by Lic. Roberto Balderrama Gómez (undated).