We sit crushed together, moist and miserable, in the back of the battered old VW van as we do every day about this time. Interesting odors assail our noses. We would rather not know what it is we are smelling. The mid-afternoon heat is beyond depressing; it is defeating. Eleven of us wait to go home, engaged in full body contact with people we know only by sight.

But the colectivo will not leave Tuxtla Gutierrez until it has at least fourteen paid fares. And that means three more people in a seven-passenger vehicle. How long will it be? ¿Quién sabe? (Who Knows?)

Most of the passengers are women “of a certain age”. They are returning home from the mercado, while I am dragging in from a day of teaching. A few high school students are also on board. (I just hope they don’t ask me for help with their English homework!) All of us want the same thing: to leave the awful heat and humidity that smothers Tuxtla on late spring afternoons and head up into the tall, blue-gray mountains south of the city. It is cool in the mountains, and less crowded. “Hace fresco,” as the locals say. We can hardly wait to get back to our village.

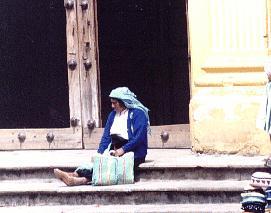

I turn my cramped shoulders slightly toward the front of the van. Four elderly Indian women–some of my Zoque neighbors who ride this route with me–sit backwards, their bags and baskets of market goods piled in colorful heaps around their bare feet. Fresh flowers wrapped in old newspapers are laid on top of the bundles. From one of the open shopping baskets a baleful chicken pecks listlessly at the little bouquets printed around the bottom of my cotton skirt. I sit very still, hoping it won’t decide to eat a run in my last pair of panty hose I brought from the States.

Then with perfect harmony, as though directed by some unseen conductor, the four women begin to fan themselves with the fringed ends of their shawls. This continues in unison for several minutes. However, since the windows in the back of the ancient van are permanently non-functional, the determined fanning does nothing to alleviate the heat.

Still seeking relief, they re-adjust their shawls almost as one. Their movements are as small as possible given our crowded conditions. Now the long end of each shawl hangs limply over one shoulder and the rest is lightly passed behind their necks. With gnarled brown hands they wad the other end, fringe and all, into a ball with which they wipe sweat from their wrinkled faces. In spite of the intense heat they still smile with their bright gold and silver dental work, and their dark eyes dance as they gossip and talk about how hot it is.

The colectivo blares its horn and three final passengers board. It moves assertively into the heavy traffic near the center of the mercado, heedless of vehicles on either side. A slight breeze from the driver’s window gradually reaches us and swirls tentatively around our red cheeks and damp necks.

Halfway up the steep mountain road we round a familiar curve. Suddenly, the air is cooler, fresher. We all sigh and feel more comfortable. We are now out of the city and almost into Copoya.

One by one, or in small neighborly groups, the women will struggle awkwardly to get out of the crowded van with their myriad purchases. Most of these will be carried home on the women’s heads. It is easy to tell who will get off at the next stop. A few blocks before the parada, another routine with the shawls will begin.

Each shawl is now adjusted so one end is very short. Only the fringe hangs down toward a deeply scooped neckline of ruffles and lace. The longer end is twisted softly, like wringing a dry towel, and circled into a do-nut shape which just fits the top of the head. As the women leave the van, those of us still inside will help each one lift her bags and baskets to this soft cushion on top of her braids, laced with satin ribbons.

Like many of us who have thrilled to the busy and colorful mercados of Oaxaca and San Cristobal, I too have a full shelf especially for my own shawls. I wear them when it is too chilly to go out in only a blouse and pants but not cold enough for a jacket. And where I live, that can be almost any day!

But I have never really gotten the “hang”, if you will, of wearing my shawls correctly. Oh, sometimes I do get one draped just right around my shoulders, and in the mirror it looks great (dare I even suggest “fashionable”?) in a color that matches my dress or slacks.

The problem is that once I move, my carefully constructed fashion statement falls away from my shoulders and droops down around my knees, one end sometimes even dragging between my ankles as I walk. My very polite neighbors must be terribly embarrassed for me!

Try as I might, my shawls require constant, self-conscious adjustment. My neighbors, on the other hand, wear them with such apparent ease. And they use them in so many different ways. I am amazed at how truly versatile these shawls can be in the skilled hands of the native women.

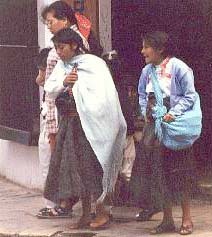

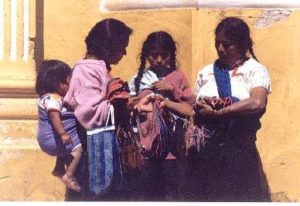

For example, tied over one shoulder they are bolsas to bring fruits and vegetables home from the corner market. Tied over the other shoulder they become baby-carriers for infants and discreetly hide the bosom of a nursing mom who needs both hands free for doing other things. Talented younger women in the village use two shawls simultaneously, thereby managing to carry the baby in one and groceries in the other while balancing a basket of flowers on their heads and holding a toddler by the hand.

The women use their shawls on cold mornings, wrapping them snugly about their necks and shoulders. As the day warms, the shawls are folded into convenient square pillows and placed on their heads, available when needed. To protect the back of the neck from a blazing noonday sun, a little of the shawl may be released to hang to the shoulders behind.

On rainy summer afternoons these same shawls cover their hair to keep it dry. In the evenings they are used as reverently as lace mantillas when the women pray and praise the Virgins (beloved statues in the village church).

Shawls cover baskets of pan dulces in transit to or from market in large open baskets, protecting them from honey bees and dust. Moisture from unavoidable sneezes is politely and efficiently captured in the fabric folds, as are coughs in crowded buses during flu season.

Warm, shawl-wrapped tortillas grace the family table for mid-afternoon comida. Ice cream dribbles are wiped expertly from fat baby chins, home-grown vegetables polished on their way to market, flies swatted, sticks of firewood tied into manageable bundles, stray animals shooed away, flames fanned, hot cazuelas lifted from clay ovens, beans picked and cleaned, fresh eggs collected, smiles made more mysterious, giggles concealed.

Now if I can just learn to keep mine on!!

30-Jul-00