“Wait,” she protested. She bent over the crouched photographer busily framing the pleasant scene for posterity, his camera at the ready, shutter cocked. She spoke loudly into his ear. “Wait!”

On the very street – no, more like a boulevard in a city of grand boulevards – where being seen is becoming the number one meaning and purpose of life, the protestations of the Doña Dueña, clearly the manager of a bistro known as SNOB, hardly made sense.

“Wait. Who gives you the right to photograph here?” Her voice echoed across the mock colonial courtyard that contained tables full of beautiful people noisily enjoying a late afternoon meal.

In this outdoor public square just off the Avenida Presidente Masaryk that is shared by boutiques, art galleries and trendy little cafes, the canopy of SNOB unmistakably dominates the view. And if the people gathered under its canvas banner want nothing more, it is to be seen. Obviously the photographer was capturing an editorial moment.

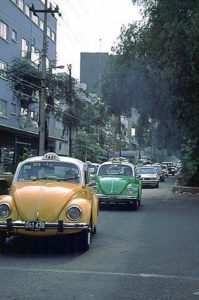

“Literary license,” was the answer to the question that drove the accuser back into the small, dark doorway under the inflated signage. The photographer snapped the picture, and left the courtyard, walking to the curb and crammed himself into the back of a VW beetle cab. It sputtered and roared away down the avenida, continuing a visual note-taking tour of Mexico City’s newest and brightest commercial star in an otherwise battered metropolis struggling to retain its livability.

Both sides of Avenida Presidente Masaryk are lined with high-end European designer showrooms, boutiques, and shops catering to the international community. Photography by Bill Begalke © 2001

Both sides of Avenida Presidente Masaryk are lined with high-end European designer showrooms, boutiques, and shops catering to the international community. Photography by Bill Begalke © 2001

This is Polanco, the Rodeo Drive of the Federal District, and it is quickly replacing the famous Zona Rosa as the city’s center of affluent commerce. It is where the Hard Rock Café located itself in a renovated mansion just off Chapultepec Park, a green space that is an oasis of tranquility in the midst of what is arguably the largest city in the world.

The cab driver, negotiating a difficult U-turn through a phalanx of pedestrians stoically comments to the photographer passenger, “There are too many people. There are too many of us.”

Mexico City is certainly one of the most crowded, noisy, polluted cities on the planet. Incongruous as it sounds, it took until the year 1900 for the city to once again reach the same population as existed in the original Aztec capital when Cortez entered it in the sixteenth century. Now the population increases by 3,000 souls each day.

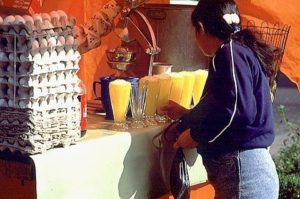

One million tourists come here too, including the taxi’s passenger now embarked upon a photographic safari of the Polanco district, then driving through Chapultepec Park to emerge on the broad Paseo de la Reforma which forms one boundary of the Zona Rosa.

Chapultepec Park serves as a kind of “Everyman’s land” between Polanco, an exclusive enclave of prosperity, and the Zona Rosa, mecca for foreign tourists, artists and the wealthy for almost forty years.

It is in the park that you will see the average Mexican and view his or her history displayed throughout the many museums located there; it is in Polanco and the Zona Rosa that you will see a show.

On Avenida Presidente Masaryk, the major arterial road in Polanco, can be found the most famous names in the world of fashion and design. Housed in buildings of gleaming marble, onyx, or gray stone edifices, protected by the best-dressed security guards in the city, all the wishes of a shopper’s lifetime can be found along the boulevard.

In the surrounding neighborhood of palatial homes hidden behind high walls, shaded by ancient trees that arch cathedral-like over the side streets, huge high-rise hotels share space with the crème-de-la-crème designer names of Cartier and Armani. The Nikko and Presidente hotels soar upward through the trees bordering Chapultepec, the Camino Real hides around a quiet corner.

A stop at one of the diverse eating establishments in the district finds the photographer sampling fresh fish sashimi at a gleaming post modern sushi house on the avenida. The interior is a simple stark pastel against black fixtures separated by glass brick. The presence of one of Mexico’s leading stars, a woman simply know as Talia, distracts the decidedly sophisticated crowd both inside and seated at the sidewalk tables under exhaust-soiled canvas awnings.

Timidly, one by one, her fans approach her table, seeking the obligatory autograph. Fearfully, they interrupt what appears to be a reunion with sisters and brothers and Mother and Father and Grandmother and extended family.

Talia shakes her shoulder length hair side to side, her neck arched backward, her long lashed eyes gazing upward at the designer halogen spotlights criss-crossing the ceiling. She giggles, inquires of each fan the name of the recipient of her largess, and dashes off a quick swiggle on the proffered piece of paper.

Outside, literally hiding-in-the-bushes, stand her bodyguards, their eyes hooded by dark-rimmed sunglasses, their left hands clutching a cellular phone, their right posed to reach underneath their tailored suits.

Life in the big city among the famous is apparently the same regardless of the big city in question. But the propinquity of so many security people must make Polanco one of Mexico City’s safest neighborhoods.

And Capitalinos have a passion for the cellular phone, and what used to be merely unnerving driving habits now has a whole new meaning with the locals talking and steering their cars through the mad rush of traffic at the same time. Even the VW taxi, once again taking the photographer on his tour, offers the use of a cellular phone for one dollar a minute, three-minute minimum.

The proximity of Polanco to Chapultepec Park insures a steady flow of visitors. The sights to be seen in the park will stagger the imagination. No less than eight major repositories of art and history are located there.

The park has been linked to the original settlement by Aztec culture in 1266 when the few hundred newly arrived tribe members held their first “New Fire” ceremony there to signal the beginning of another 52 year calendar cycle.

Today Chapultepec, an ancient word meaning the hill of the grasshoppers, contains some of the finest museums and art galleries in the hemisphere. It is also the location of the presidential residence, Los Piños, and the former presidential palace, itself site of Emperor Maxmillian’s court, and before that, a military academy that figured prominently in the Mexican-American war, and originally was one of Cortez’s residences.

Below the palace, at the base of the hill, a quick turn and the VW taxi enters the Paseo de la Reforma that extends eastward. Emperor Maxmillian ordered it constructed, modeling it after the Champs Elysées. He died by firing squad a few years later, never witnessing its formal dedication by the very man who sentenced him to death.

Originally, magnificent townhouses and villas constructed of gray-stone reaching four stories high with pitched roofs and ornamental iron work built in the French style reminiscent of Paris lined either side of the boulevard. Many still survive in the Zona Rosa.

As the Paseo intersected with other major avenues, the city architects created glorietas, gigantic traffic circles that entomb monumental sculptures at their center. These roundabouts broke the monotony of the beautifully broad, green-fringed boulevard. The huge trees which grew to shade both travelers and park sitting natives alike have suffered from the sad legacy pollution has brought to the city.

Today, lining the curbs are modern glass towers, art deco classics and colonial palaces interspersed with garish commercial businesses, first class hotels, and the omnipresent Sanborn drug store. The area between the Paseo de la Reforma and Avenida Chapultepec is technically the Zona Rosa, the pink zone.

The glorieta that houses the monument to Mexican Independence, better known as El Angel, informally marks the beginning of the Zona Rosa. There is subtle irony in that nickname, for the statue, though referred to in the masculine tense, is clearly a feminine figure. Machismo dies hard in the captial.

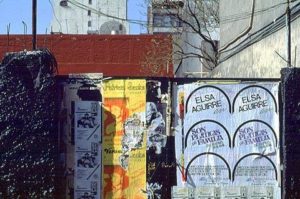

Similarly, the Zona Rosa purports to be fashion and trendiness, but behind the shop-fronts are some of oldest, most elaborate buildings still existing in the city. A contemporary façade can conceal a century of history.

The name of the first resident to convert the street level parlor of his townhouse into a retail store, a tienda, is lost to time. Since the early 1950’s, most of the first floor levels became the art galleries, boutiques and bistros that made the Zona Rosa infamous.

But even a VW is a large car for the narrow streets of the zone, prompting the photographer to abandon the trusty taxi to enter the district on foot.

The streets were named for European cities during a period of infatuation with things European. Rutted and rolling though the pavement is, the sidewalks are an obstacle course because of damage done by years of earthquakes and demolition.

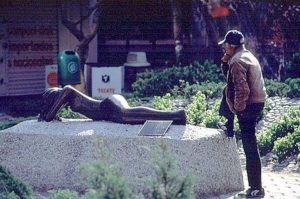

Scattered in each block are vacant spaces awaiting re-building; a modern mall consumes a quarter of one sizable city block. One section of the zone has been turned into a pedestrian mall, complete with large artistic nude statuary, quite unlike the historical cast-iron clutter found along the Paseo de la Reforma.

There on the Paseo connecting these two commercial centers of the city, statues to heroes of the revolution(s), metal visionaries from the past, all point lifeless arms to the future, a future that Mexico City is having difficulty dealing with.

The clutter to be found in the Zona Rosa will most likely be a homeless person, huddled in the darkened doorway of a still-existing home, hand outstretched for a few meager pesos thrown by sympathetic capitalinos.

Young boys rush vehicles caught at intersections, dousing windshields with the spray from plastic bottles, then toweling them off for a peso tip. Incredibly, others stand on street corners, spitting gasoline into the air, igniting it in an instant to become fire-eaters for a few coins.

People charge by, driven by the mad pace of this city, by the magic and excitement that lives side-by-side with the crowding and poverty.

It is as if, within this city, deafened by the clamor of jack-hammers and stone chippers, the people still embrace life as it is for all the very same reasons that others would strive to avoid.

“Wait,” in Mexico City applies only after reaching the goal, never to the middle of the journey.