The Saturday movie-matinee feature of pre-television history introduced my entire generation to the mystery and adventure of lost cities lurking in the dank depths of the world’s remote jungles. Great white hunters slashed their way with machetes through vine-infested rain forests seeking the treasures of civilizations long gone from the earth.

In the third reel of the film, usually with the discovery of crumbling stone ruins, came the attacks from the painted, loincloth-wearing, spear-throwing indigenous natives, rising up to defend the sacred temples of the mysterious past from the interlopers. Steven Speilberg capitalized on this boyhood fantasy when he conceived the first film of the incredibly successful Indiana Jones trilogy.

The reality of that fictionalized romance lives on today in the Sierra Madre de Oriental mountains (the Mother Mountains of the East) of Querétaro state in Mexico, although they are perhaps better known as the Sierra Gorda, the fat mountains.

To be truthful, however, there are no great white hunters involved in this story; the indigenous natives wear jeans, drive pick-ups, and sell fruit drinks to the visitor; and the only use for machetes is to protect against the occasional snake.

But, for this story to be a movie cliffhanger, clearly there has to be some element of danger in visiting the sky cities of Ranas and Toluquilla perched atop ten thousand foot mountains in central Mexico. Unlike the Saturday afternoon movie thriller, however, the excitement in this real life version comes both from the journey and the discovery that history can be stranger than fiction.

The fact is that no one truly knows who built these sky cities, or exactly when, or what eventually happened to their inhabitants.

What is known is that only a portion of the ruins have been excavated and that the prime occupants were a privileged class of priests. The people are believed to have had contact with both the Toltec and Teotihuacan cultures and trails radiate down and out from the sky cities like the spokes of a wheel to all points of the compass.

Their society was uniquely centered on mining, in contrast to the rest of pre-Hispanic Meso-America. The minerals most sought after included cinnabar (mercury), calcite, and fluorite, the possession of which was a symbol of social rank and wealth.

The sky cities were abandoned in the tenth and eleventh centuries, long before their total available land for settlement was used up, and the mining and farming society gave way to nomadic hunters.

The ultimate inhabitants, the Chichimeca Indians, who discovered the abandoned cities nearly eight hundred years ago, were the only tribe in Mexico never subjugated during the Spanish Conquest, and they repulsed attempt after attempt to dislodge them from these heights.

Historians and experts working with the tourism department of the state of Querétaro have organized visits to the ruins that give travelers seeking adventure and knowledge, a comfortable alternative to weeks of hacking through the jungle. One expert, Dr. Morton Stith of San Miguel De Allende, who lectures at that city’s famed Biblioteca Publica, has visited the ruins numerous times and leads field trips to them. A participant in one of his tours can experience the mystery of the past and still be back to a comfortable posada, a local inn, in time for happy hour, a satisfying dinner, and a comfortable night’s sleep.

Unlike the more widely known and visited archeological sites dotting the Yucatan peninsula or Oaxaca state in Mexico, the sky cities were built atop mountainous ridges for both protection from attack and to isolate the priest class from the common people who lived far below in the valleys raising the food to support the aristocracy that overlooked them.

The only known comparison to these Mexican wonders would be Machu Picchu in Peru, but it was constructed as a final sanctuary for the Incas from the Spanish conquerors hundreds of years after the sky cities were abandoned by their builders.

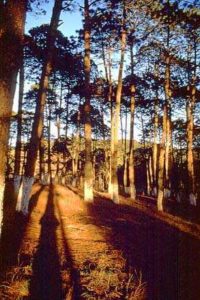

Those who participate in this time-travel visit to the sky cities can testify to the difficulty in reaching Ranas and Toluquilla—it takes hours of travel across an ever-changing landscape to reach the sites. A new multi-million dollar highway climbs from the desolation of the high desert, ascending switch-back curves through Joshua tree groves that give way to pine forests swathed in mist. It is the only way in.

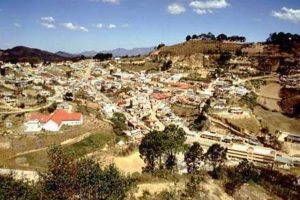

Then, across a great rift canyon, the pueblito of San Joaquin comes into view, a small terraced town built at the base of the peak where the ruins of Ranas are located.

There is a small, very basic hotel in town and nearby is a state park that provides camping facilities for the serious backpacker. Field trip participants are usually lodged at a state-run youth camp that provides comfortable dormitory style sleeping arrangements.

Ranas is the first ruin to be visited; just beyond the town, above the last house on the road up the mountain, the traveling gets difficult. The climb to the final summit to reach Ranas, “The Frogs,” is difficult but spectacular when finished.

While the ruins at Toluquilla, translated from the Nahuatl and Spanish as “Little Hunchback Peak,” are a short fifteen-minute drive from San Joaquin and located atop a long, undulating ridge line, the path to reach the summit is much worse than Ranas, but the rewards are greater.

The dirt and rock path from the tiny parking lot to the ruins of Toluquilla leads another three-hundred feet up a 45 degree slope to the summit. If the burros grazing on the steep slope of the mountain below the ruins sometimes have difficulty in making the turnaround to climb down to their home, one wonders how a tour bus is going accomplish the same thing just finding a place to stop to disgorge its passengers.

Even while one is climbing up the trail the view of the summit and its architectural treasures remains invisible until the very pinnacle is reached.

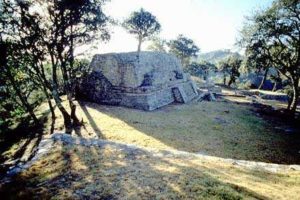

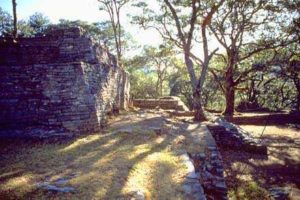

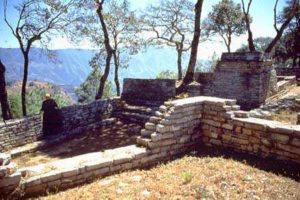

The struggle to reach the top is worth the effort when finally reached, for stretched out before the visitor on the serpentine ridge are the ruins of an ancient city: the chiseled-rock remnants of public squares, ball courts, temples, shrines, and the residences of the elite priesthood– all connected by cramped stone pathways.

The summit is no more than a hundred feet across at any one point; the cities cling to their ridge lines like a nervous tight-rope walker, just a step away from the abyss that lies hundreds of feet below. What has been uncovered of the ruins today is only a small fraction of what is there, perhaps only 15 percent.

Looking out from the pinnacle, distant mountains fade into the haze, looking much like a Chinese watercolor with their sharp peaks and steep valleys. The surrounding slopes reveal modern scenes of habitation, but they have been cultivated through the centuries since the Conquest. Pastures and corn fields, huge electrical transmission towers, and small pueblos nestled in the narrow valley floors are all visible from the Olympian heights of the sky cities.

What is remarkable is that the sky cities went unnoticed and untouched for centuries after they were abandoned. Of course the native people always knew they were there, but had no idea of their significance or origin, since their history was lost in the hundreds of years of Spanish occupation.

That is the true attraction and mystery of the sky cities. Any attempts to understand and reconstruct the culture and civilization that conceived these impressive edifices high above the jungle floor are mired in the accumulated dross due to the total lack of recorded knowledge about their existence.

It has only been within the last fifty years that sporadic attempts have been made to bring back the past glory of these mountain-top aeries through excavation and restoration. Recently the sites have been opened to tourism in the hope of generating the interest and revenues necessary for a full restoration.

Therein lies the double-edged sword. To increase public awareness through tourism will probably diminish the singular nature of this encounter with the past. Yet, without that awareness, these priceless examples of the genius of mankind could easily be vandalized and destroyed by either an unknowing populace or unscrupulous collectors.

The fact that the local government is utilizing expert assistance testifies to their commitment to proceed to the goal without jeopardizing the conclusion.

Certainly, these sky cities bear no resemblance to the great ruins of the Yucatan, whose temples tower over the jungle floor. The tallest partially restored pyramid of the sky cities stands less than one hundred feet above its ridge top. But scale and size pale when considering the sky cities’ empty courtyards, silent ball courts, vacant pyramids, and deserted corridors. What is revealed is a more fulfilling and powerful experience than the better-known archeological sites to the south due to that very fact—the absence of an overwhelming number of visitors.

The sky cities resonate with loneliness.

It’s as if the visitor was the great white hunter from those Saturday afternoon action adventure movies. These stone cities laid out before the visitor are extraordinarily quiet—only the hum of the locust, the calls of birds, and the wind whispering through the over-arching pines breaks the silence.

Turning the next corner down the narrow stone walkway from the plaza you expect the ferocious painted face of a native to suddenly leap into your path and utter a blood-chilling scream before plunging a spear in your direction.

The thought seizes your mind about spending a full moon night there, silently listening for the voices of the past to break through the symphony of sounds and cast you back to an unrecorded time.

To a time when the gods walked upon the mountain tops.