A written and photographic experience

Of all the most endearing and enduring charms that draw travelers back to Mexico, the effect that the country can have upon a sense of humor is the most magical.

It arises out of an initial attitude of annoyance and frustration by the first-time visitor toward anyone or anything that appears to behave or operate in a manner other than “normal.” To that visitor it is all foreign. Over time, the personal sense matures into a recognition that the people or things are odd indeed, but quite Mexican for Mexico.

Once that leap of faith is accomplished, the fractiousness of Mexican life becomes as observable as the skull of death does atop a carved wooden skeleton. There are three words for it: sentido del humor, sense of humor.

Once this state of mind is achieved, it is not uncommon to encounter snippets of life in Mexico that cause almost instantaneous vocal laughter and internal mirth on the part of the observer. Of course, everyone else nearby will think that the outburst of merriment is muy loco.

The following five examples may help serve to visualize and understand the insightful vision leading up to the inevitable climax. One of them is quite dramatic, another quite charming on the surface of it, and they all could be classified as either romantic tragedy or black comedy.

Item #1.

In an attempt to combine efforts among Mexican states and the neighbors of Central America, Mundo Maya, the Mayan World tourism project, was initiated to bring the traveler back to Chiapas and other notable sites throughout Southern Mexico.

Chiapas, of course, has been in the news these days because of an indigenous uprising over five years ago that has been in on-and-off negotiations between rebels and government officials with 25,000 troops still in the field and the masked revolutionaries hiding out in the jungle.

To prove that things have indeed changed and progress is being made, a decision by the tourism officials placed the opening ceremonies of a promotional tour of the Mundo Maya’s five Mexican states, at El Chorreadero waterfall near Chiapa de Corzo.

This magnificent location at the base of fractured-stone cliffs, rising 600 feet above the natural amphitheater created by the crashing cascade, was a photo-perfect setting for federal and state tourism officials, so they assembled the symphony orchestra and chorale from the Arts and Sciences University of Chiapas, and assorted dignitaries and reporters.

A noted Chiapan poet who participated in the inauguration, Elva Macias, was quoted as saying, “The living cultures in this state, including its music, clothing, language and customs, are just a few of the attractions that will interest travelers who come to the Mundo Maya.”

Not exactly poetry, but encouraging words none-the-less.

Obviously the venue at the base of a towering, pounding waterfall, its drops of mist clinging to the air, the musical instruments and the faces of those gathered there, played a major part in this production.

And what a production there was. The canyon walls reverberated with the rolling melodies of “Water Memoirs,” an original piece composed and conducted by Federico Alvarez del Toro. The imaginative composition included two notable passages, the first, a tit-for-tat showdown between amplified electric guitars pitted against marimba soloists banging their wooden mallets, flooded the canyon with deafening music.

The second exceptional passage involved the trumpeting of conch shell horns and screaming electric guitars backed by the entire symphony orchestra and chorale. It rattled the very granite walls surrounding the waterfall, so much so that rocks began to give way and crash down the cliff toward the celebration.

Flute soloist Marielena Arizpe was injured by one such boulder dislodged by the cacophony in the canyon. She was reported to have been evacuated by the Red Cross and was in stable condition later in the day. Festivities, foreshortened by events, were concluded with soldiers firing off cartridges filled with confetti.

Exit the tourist bureau bureaucrat who thought it all up.

Item #2.

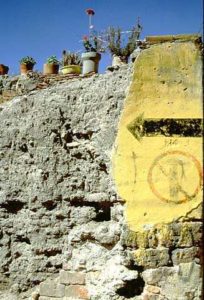

Any visitor to Mexico, whether walking or driving a car, knows to look up at the walls of buildings at each street corner. Half-way up the wall, painted on a black background, is a white arrow, either one –> way, or two <—> way, or a “do not enter Ø” sign will confront them.

This procedure is enormously necessary in the colonial cities region of Mexico, the very heartland of its history, agriculture and industry. The streets of many of the cities that comprise this region are old, very dark and narrow, and constructed with cobblestones. The corners are blind, and the streets themselves undulate with topes, speed bumps that can flatten a car’s undercarriage or bend a frame when navigated too swiftly.

However, the selection process in determining how the traffic grid is to function escapes Aristotelian logic. One-way streets intersect with two-way streets, dead-ending in cul-de-sacs that turn around into glorietas, – traffic circles going nowhere.

In an attempt to spend as little effort, gas and time as required to arrive at the requested destination, a typical taxi driver, upon intersecting with a one-way street that prohibits forward movement, will simply turn the car around, slam it into reverse, and drive backward up the one-way, in effect observing the signs and the law.

Item #3.

Another beautiful sunny day on the Pacific coast had begun at noon as usual for the tourists. On the drive toward town they spotted a restaurant that looked inviting located just off the highway and built directly on a broad white beach. An empty sand-packed parking lot, large enough for fifty cars, was lined with wind-beaten lime-yellow splotched palmettos lashing about in the cool on-shore breeze. The smell of salt spray mingled with the slightly off-smell of kitchen grease and fish was apparent the moment the threshold was crossed.

The red-tiled dining room featured an open wall of French doors facing the sea, with the invading wind rustling the crisp white table cloths and spinning the suspended shell sculptures slowly in one direction, then the compounded string-power overcame the breeze to unwind the shells in reverse. A wide balcony fronted on the sand, and a stone staircase descended to the blinding, blistering playa.

All-in-all, it was an ideal location for a leisurely seafood lunch. Of course in Mexico, the main meal, in the early afternoon, is the comida, but that rule does not seem to apply to resort areas and the restaurants serving them.

Although European visitors mimic the Mexican way, gringo tourists demand a big evening meal, so the local people adapt their kitchen schedules to respond to the trade. If there are more gringos than Europeans and Mexicans, then the big meal is at night.

This restaurant initially appeared to cater to the national or European tourist, not the gringo. But the assumption that business would be in full-blast proved terribly wrong because no one except the help inhabited the space at that hour. This must be a gringo-phased kitchen. Nevertheless, the staff cheerfully whisked the American tourists to a cool table near the open sea-front terrace.

“¿Tomar?” The waiter swiftly took the drink orders down on a small slip of paper. The drinks arrived with all due speed, considering no other customers were competing with the overly gracious help for attention.

After a second round of drinks the meal was ordered, each selection full of the wonderful bounty of the sea so plentiful along the Mexican Riviera. The pounding surf grabbed the attention of the customers and so they ventured out upon the beach, grasping botellas of cervezas as they hop-scotched across the bright burning sand to the water’s edge.

Time and tide came and went, bottles were drained dry, and their hunger increased. A swift return to the table revealed no food, but an anxious waiter ready to take another drink order. His fellow workers, meanwhile, had huddled together outside the main entrance to the restaurant where a steady stream of cars and taxis would arrive, but no one would exit them.

Instead, as each vehicle stopped, a package or paper bag would be handed to one of the help, who in turn would run into the restaurant and immediately enter the kitchen through swinging doors. From behind those doors came the sounds of a kitchen at work, so why not have another round, and move this party to another table because the sun is really hot pouring through those open doors onto this one.

The afternoon just got away from itself, the hours passed as quickly as the waiter was available to replace a finished drink. The flow of cars finally stopped. The dining room still remained empty except for the original customers.

Four hours after deciding upon this as the typical Mexican restaurant, a wonderful meal of just-bought, freshly-caught, just-unfrozen food that had been arriving at the front door since soon after the order was placed was finally served. Travel experts say that when eating in a foreign land, it is wisest to eat just-cooked food. In Mexico, the food is so fresh the kitchen doesn’t even have it when you order.

Item #4.

The classic VW beetle parked at the stone curb, lucky to find even such a small space available on the busy street. The doors of the car swung open to disgorge the passengers.

At first, the event took on no special significance, until the number of people piling out of the basic four seat car became apparent. The assembled count of passengers exiting the car ended at seven, of all body sizes and ages.

A casual foreign observer making a sotto voce count as the disgorging continued caught the attention of one of the passengers, a young woman, and she began laughing and sharing it with her passengers, most likely her total immediate family.

She repeats the count back in English to her fellow travelers, “One, two, three, four, five, six, seven.” The family proceeds to laugh, not with rancor or negativity, but simply in amusement that someone would find the incident unusual. It is simply another one of those special shared moments regardless of cross-cultural differences that transcend the human condition.

Item #5.

This final vignette will reveal volumes about the necessity for a sense of humor in Mexico.

The expatriate woman who hired a maid was extremely satisfied with her job performance. The maid accomplished everything in fine order, but had one fatal flaw. She always arrived for work a half-hour late.

After being berated by her employer about coming to work promptly at ten, but time-after-time she continued to arrive late, the maid finally became frustrated and spoke to the woman.

“Señora, what time would you have me arrive? Would it be eight, nine, ten? It is of no importance to me.”

The Señora says ten o’clock is all she’s asking.

To which the maid replied, ” Si, Señora, but I can’t be on time.”