The most important visual image in the classic film, ” Close Encounters of the Third Kind,” was not the alien spaceship, but the imposing stone monolith chosen as the site of the encounter. In an attempt to understand the significance of his mental image of that place the star of the film almost goes mad.

It should come as no surprise to the traveller that the fictionalized location exists in fact as Devil’s Tower National Monument in Wyoming.

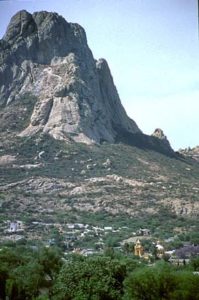

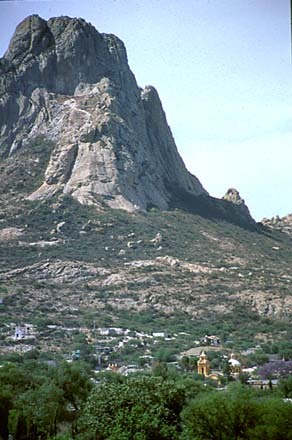

What is astonishing is that a similar geological feature rises over one thousand feet above the high desert of Mexico, and has been considered for eons in native folklore and myth as “The Navel of the Universe.” It is more than merely similar, it is magnetic.

Today, at the base of this Mexican monolith lies the town of Bernal, muy tranquilo in the sun. It is a nascent folk art and craft center, and is slowly becoming a new retreat for artists escaping the tensions and crowding of a modern, digitizing world.

Bernal is the center of a region that contains other gems of Mexican beauty and history: the cities of San Miguel De Allende, Pozos, Querétaro, Guanajuato, and Tequisquiapan. It is a region not frequented by tourists, or spaceships for that matter.

But it should be.

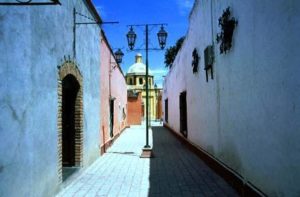

The historical importance of these cities in shaping Mexico today is almost eclipsed by the beauty of their colonial architecture. For these two reasons alone, although there are many others, the visitor should seek out this Mexico not found on the package tour.

But it shouldn’t be.

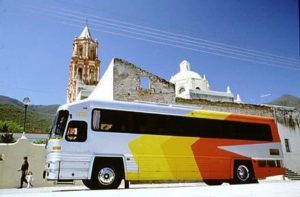

Central Mexico should be examined in a more leisurely, Mexican way, taking time to walk the streets, but traveling the highways in a bus. Buses are the preferred means of transportation in this nation.

The varied classes of bus service, from the gleaming Mercedes Benz monsters complete with TV and snacks and a usually operating baño to the former Bluebird school buses still struggling out a living for the owner, all crisscross this heartland of Mexico, allowing the visitor the opportunity to pick and choose an independent schedule with more time devoted to a slow walk through history.

Begin this marvelous journey in the birthplace of one of Mexico’s greatest heroes; stop at a city abandoned to time and the wind, once one of the richest cities of the New World. On to the one that is perhaps the most Mexican of cities, where a foreign-born emperor was executed and a president gave away half his nation to settle a war, all to the roll of drums; then arrive at the city where the great hero was martyred in the nation’s quest for independence from Spain.

Spend a little time next at a weekend retreat that fulfills the requirements of a Palm Springs escape, but without the overhead. Return to the Navel—Bernal—to center yourself with the universe before checking out for home.

You can reach the starting point of San Miguel from the capital, Mexico City, Districto Federál. A more convenient and less hectic arrival can be made through the airport in León, the state of Guanajuato. Fast luggage retrieval, efficient immigration and customs, and out you go through the exit to board a first class bus bound for San Miguel.

Don Ignacio De Allende, one of the four founders of the revolution that ultimately took all their lives and eleven years of war to conclude victoriously, was born in San Miguel, now named San Miguel De Allende to ensure that everyone knows it is this particular San Miguel out of the countless ones that dot the land, and certainly no other.

It is also an artists’ colony, has been one for years, and, over recent time, has become a center of learning with the establishment of the Instituto Allende and the Bellas Artes, both schools of the arts, along with language academies. Now the University of the Valley of Mexico has opened a campus for students pursuing careers in business.

That makes this a town of professionals, but the visitor is happily surprised to witness a harmonious mix of people living side-by-side, not to mention the roosters, dogs and occasional pig on the next rooftop.

It also happens to be a very beautiful place.

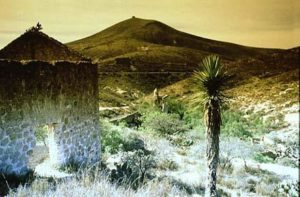

It sits in the middle of a desert of mesquite and cactus, a multi-hued painting of itself on a canvas of beige and brown and gray, with a annual verdant background change every rainy season.

A very hostile and opposite world will be seen in Pozos, a short distance by bus. Everything about Pozos is a sunburn shade of yellow: the ruins, the soil, the rocks and brush. It is a ghost town as riddled with mine shafts as a rotten tree is with termites. One false step and the next stop is 800 feet down. Its soil and the water that now fills the shafts are polluted with the minerals used to extract the silver ore.

It is quite otherworldly. And vacant. And one man has the key to it all.

Not by coincidence he also runs the only hotel in the still inhabited surviving village, which boasts very little else except for a small museum, craft shops featuring native musical instruments, and a soaring smooth-stone walkway, three hundred feet from bottom to top, up to the doors of a church. Its use is intended for the knees of the penitent.

“And what,” you ask, “is the significance of Pozos in this bus ride through history?”

It’s mines were simply one of the main sources of Spain’s wealth, then Mexico’s.

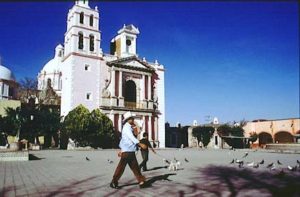

If Pozos was a “City of Silver,” then pretender to the appellation “City of gold,” would have to be Querétaro. Today it is a prospering, industrializing city of historical proportions. Through it runs one of the largest remaining examples of a colonial aqueduct system, its graceful arches a national monument, soaring hundreds of feet in the blue sky.

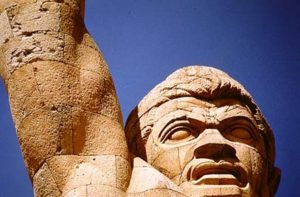

Piercing that same sky is an enormous statue of Benito Juarez, considered by many the father of the newest Mexico. The stone eyes, filled with apparent but inferred anger, gaze down upon the city in which the Treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo was signed by Santa Ana.

That document ceded half of the nation’s land mass and most of its wealth to the neighbor to the North. Here, too, a foreign-born duke turned emperor, in an elegant square lined with the trees he had ordered planted, placed gold coins in the palms of his firing squad so that their bullets would not disfigure his face.

His reign ended. His tactic failed.

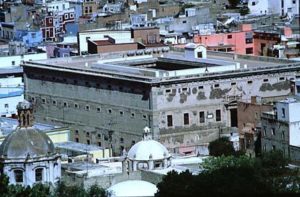

Yet his fate is still a far cry from that of Allende, the patriot. He was beheaded and later, in Guanajuato, the capital of the state where San Miguel is located, his severed head was placed in a cage, and suspended from one of the four corners of The Granary, La Alhóndiga. From the other three corners hung the heads of his co-conspirators, Hidalgo, Aldama, and Jimenez.

Ironically, however, the largest statue overlooking this city most enamored with things Spanish is of “El Pípila”, the Indian who history records as being responsible for destroying the huge wooden doors to The Granary during the 1810 revolution, thus permitting the slaughter of the Spanish who had taken refuge there, and turning the tide against the uprising.

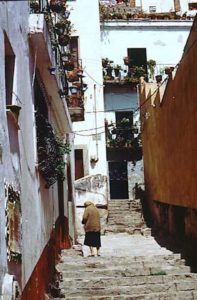

Beyond the infamy of its past, today Guanajuato boasts theaters and international festivals, such as the reknowned Cervantino, and a maze of picturesque narrow streets lined with Colonial and European inspired buildings.

There are sidewalk cafes reminiscent of Paris or Rome, traffic-free boulevards, probably the world’s first example of an underground expressway, the home of Diego Rivera and the greatest iconoclastic collection of the Lord of La Mancha kitsch since Graceland personified the genre, plus a whole lot of mummies.

Those are worth missing.

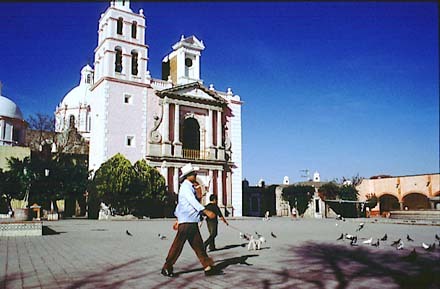

Drive from Guanajuato over the mountains and desert to the resort town of Tequisquiapan, a weekend refuge of many upper class Mexico City dwellers. The downtown streets are among the cleanest in all Mexico. The imposing colonial architecture isn’t all authentic, but the renovations mix well.

The beautiful plaza and its church are surrounded by upscale shops, restaurants, and posadas, small inns. Around the edge of the city’s center are the large resort hotels, some of them renovated colonial haciendas, usually a rambling two or three story ranch-style built around a central pool and garden.

The nearby mountains contain some of Mexico’s opal mines, where a bumpy ride, rattling down a cobblestone road, ends in the dusty streets that embrace the pueblito of Trinidad. Beyond the door of a nondescript house, spread out on a table in the kitchen for inspection, there is the treasure of trapped fire. Dozens of shimmering opals in matrix, an inferno of them, glare out from behind the stone in which they were created.

A few hours more of travel to circle Bernal and finish back in San Miguel. That city’s jewelry cases are full of the transformed flame from Trinidad, now burning in cold silver settings. The antique stores, usually located in rooms and a court of a beautiful colonial house, are crammed with actual and re-created colonial furnishings.

Decorative angels are a big item these days with designers; carved wooden winged angels hang from every ceiling, adorning every wall of these shops.

In considering the cosmic significance of angels to many cultures, especially Christian theology, questions arise as to what exactly are the representations sold in the shops?

As defined by Dionysius the Pseudo-Areopagite, there are three levels of hierarchy among angels, and atop the highest rung of the level closest to God are the Seraphim.

They can stand before God, but His white radiance is so brilliant that even they must fold their wings over their eyes. Each tier of angel has three levels of its own, only the lower two deal with mankind. In descending order of nearness to God after Seraphim they are Cherubim, Thrones, Dominations, Virtues, Powers, Principalities, Archangels, and mere Angels.

Considering the almost bureaucratic distinctions, one wonders if angels came from the source of EVERYTHING flying by themselves…or in a ship of some kind…and whether they have navels like the carved angels in the shops?

And are they “innies” like the wooden ones or “outies” like the Navel of the Universe in Bernal?