In the novel “Virtual Light,” cyberpunk author William Gibson envisages a Mexico City of the near future where the air is a sooted ebon and the populace wears oxygen masks.

It might seem far-fetched, but with the city’s population topping 20 million, and the city’s cars about a third that number and all of it increasing by the day what, in fact, might the future hold for this city? What will it be like a century from now? For that matter, how about a mere decade from now? For some artists and thinkers native to Mexico City, the apocalyptic “future” came and went. The metropolis has already endured its gotterdammerung.

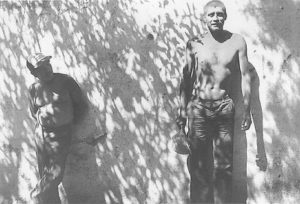

Yet the people are still here, and so is the city: a vast behemoth belching barrios for breakfast; spreading, growing, bursting at the seams of the Valley of Mexico. For photographer Pablo Ortiz Monasterio, Mexico City is a “post-apocalyptic metropolis.” In the words of Jose Emilio Pacheco, the city has “refused to accept the many declarations of its death.” Pacheco writes the forword to Ortiz Monasterio’s new book, “La Ultima Cuidad” (“The Last City”) a photographic record of the dust, decay and urban misery which permeates Mexico City; and also the vitality of life which keeps it running.

The book is the culmination of more than a decade’s work. Throughout the 1980s, Ortiz spent one day a week getting up at dawn, pinpointing a route from a city map, before heading out to photograph what he saw until night fell. “The idea was to see all the city,” Ortiz said. “To go everywhere.”

The project grew from being a straightforward document of the city and its inhabitants into a passionate, symbolic journey through the soul of the nation’s capital: “the shipwreck of a city which floats upon the mud of its dead lake, upon its faultlines, upon all its unresolved social problems…” “The city keeps transforming itself so much that a description seems futile,” Ortiz said. “The size of it is so immense. I had to change my plan and work more in terms of evoking it. What does one feel to be in the streets of Mexico City?”

The book has taken a good stab at it. The photographs include images synonomous with the beat of the streets: children selling chiclets; spontaneous outbursts of nationalistic fervor: a man hunched in the open boot of a car, hoisting the Mexican flag; laughing shoeshiners; people on the phone; a pregnant woman waiting to catch a bus; dust and cars and graffiti and miles of concrete.

Ortiz took “tens of thousands of photos” during his wanderings over the length and breadth of Mexico City. Out of those countless images, only 60 could appear in the book. Ortiz started the photo editing in the early 1990s and it took three years to whittle out the chosen shots.

“The pictures I chose weren’t necessarily the best. They were sorted from three dividing themes,” Ortiz said. “There were those with symbolic value, which give the threatricality of desolation. Others give you atmosphere – the smoke and noise. The third category gives you the rhythm, the city streets filled with life.”

The mansions lining Reforma’s wide avenue after Chapultepec Park are not featured in “La Ultima Cuidad.” Nor are the beautiful people of upper class Polanco district’s streetside restaurants. Ortiz’ “selective mirror” ignores these ever-shrinking pockets of affluence, concentrating on the wholesale poverty which has all but submerged the city.

Poverty is the defining equation of urban life in the D.F. It is a city of the poor.

“In a way, the middle class don’t even belong here,” Ortiz said. “When I started this project there were five million people less than there is now. And these additions all belong to the poverty group. Get out of Polanco or Lomas and what have you got?”

Pacheco writes: “at the close of the 20th century, it is the poor (who are Mexico City’s) natural inhabitants. The rest of us… have become foreigners.” Grim stuff. It gets grimmer. Ortiz shows the fatalism and violence which lurks just beneath the devil-may-care exteriors of tough punks living in dusty, outlying barrios of the stripped, northern hills depressing netherworlds the average tourist must shudder at when passing them on the way to Teotihuacan. Here Ortiz, the local, played tourist, capturing with his camera unemployed youths shooting off fireworks and playing with guns. Passing the time, you might say.

In one photograph, taken during the yearly Semana Santa Passion Play in Ixtapalapa, the “Christ” lies blistered and bleeding, waiting to be hauled up on the Cross. He symbolizes both the misery and the faith of all the Indian poor who have been exiled to the city from barren lands and pueblas all over the Republic.

The theme of religion pulsates through the book. The photography evokes a stanza from Hector Carreto’s poem “The Cathedral:”

“And there is nothing to be done,

the cathedral is sinking

taking the City of God

away to a land without stars.”

Yet there’s a light at the end of every tunnel. The last image in “La Ultima Cuidad” is that of a tree, summoning the mute courage for another day, to absorb the fume-choked air and keep living.

“People still have a capacity to be happy, to love not just here but everywhere in the world,” Ortiz said. “The vitality to live and laugh is still there. ”

An English version of the book, “The Last City,” has just been released in the United States on a first edition print run of 3,000 copies, and is selling well. The Spanish edition is available in Mexico, and is published by Casa La Imagenes.

“La Ultima Cuidad” is Ortiz’ fifth photography book. His next project will concern village life surrounding the Popocatepetl volcano, a way of existence often threatened by the “smoking mountain.”.

Mexico City as reality bespeaks the future of all urban life on the planet. As in Gibson’s blighted world, or even today in other cities such as Bangkok, Jakarta and New Delhi, everyone loses when the environment in which we live is allowed, through corruption and indifference to go to wrack and ruin. “Like it or not, this is what we are,” Pacheco writes in “La Ultima Cuidad,” underlying Ortiz’ wisdom that if we’re going to arrest the course of the city’s demise, we’d better get cracking.

“To solve anything you have to look at it, collectively, el frente, straight on, ” Ortiz said. “And then you say: What can we do?”