Coyote doesn’t offer a word to guide us

through this mysterious and arduous process.

He leaves us to our own world, to our private vision quest.

The sweltering heat of the lodge is suffocating.

Sweat drips from my body

and mixes with the earth I sit on, creating mud.

The amber necklace I’m wearing begins to burn my skin.

Struggling with the hot clasp, I tear it off

before it leaves a permanent mark on my neck…

This article by Kim Kroonenburg describes a personal Temescal

or sweat lodge experience in Northern Mexico.

For centuries Native Americans have been following the tradition of mind, body, and spirit purification by entering the sacred Temescal, or sweat lodge, on nights of the full moon. It is considered the womb of the earth, and one enters the lodge to reemerge into the world reborn. This ritual is held on the property of a 90 year-old Shaman elder, a man who welcomes all visitors prepared to experience the power of this legendary cleansing ritual.

Night falls and the full moon looming over the horizon illuminates the resurrection of this ancient custom. Rattle and towel in hand, I sprint down the path, past the garden of San Pedro cacti and Rosemary bushes. Dressed in respectful attire of a sarong and long sleeved shirt, I join the other visitors gathered around the smoldering fire pit.

The fire has been burning for three hours, time enough to thoroughly heat the twenty-eight lava rocks buried within it. They will serve as the source of heat and purification inside the Temescal. The conch shell lets out a last bellowing call and warns any remaining straggler that the ceremony is about to begin.

I hang my towel on the nearby fence and breathe in the perfumed air: the smell of burning sage prevails. Regarded by Native Americans as the most important cleanser of negative energies, the plant is an integral part of the Temescal purification process.

I watch the serene, half-lit faces of the other visitors as they gaze into the fire, calming their minds for the ritual. Most of them are devoted participants who return every month, but for a few others the sweat is a new experience.

All is dark and quiet except for the scene that lies before me: the sweat lodge. Lit by the flickering fire, the lodge is a dome shaped structure made of a skeleton of fastened willow branches covered by thick tarps. It measures 5 feet in height and 10 feet in diameter, large enough to accommodate 20 people. The entrance faces east, the direction of the rising sun.

Beside the dome, a tall beaded power staff rises from the earth, serving as protector and conductor of energy. Offerings from the participants lie beneath the staff on a mound of dirt, serving as an altar: drums, crystals, medicine pouches, exotic herbs and large quantities of sage. I lay my rattle on the mound and allow it to purify before taking it into the lodge with me. Tobacco is also offered, an essential component to many Native American ceremonies. Tonight pure tobacco isn’t available and a Marlboro cigarette suffices, mixing oddly with the clutter of ancient Shamanic props.

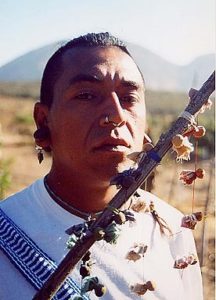

My attention is drawn to the opening of the sweat lodge as Coyote, the leader of the ceremony, emerges from the domed structure. Humble in his power, he’s a peaceful older man known for his gentle and intuitive guidance of the ceremony. Having finished cleaning and preparing the lodge, he announces the start of the ritual.

The participants line up around the fire: women first, followed by the men. I take my place near the front of the line and watch as those before me melt into the darkness of the tarped formation. At the entrance of the sweat lodge stands Hombre de Fuego -Man of Fire- the chosen fire-keeper who tends to the fire and heats the rocks. The fire used to warm the stones must be created according to basic Shamanic principles: offerings of tobacco must be made to the four directions -North, South, East, and West- and prayers are said, appealing to the spirits to infuse fire and rock with the power to purify the warriors who enter the lodge. All those who enter the Temescal are considered warriors because they have the courage to challenge their demons; in doing so, they purify themselves.

Hombre de Fuego holds a metal can of burning sage and wafts the smoke around me with an eagle feather. This “smudging” procedure purifies a person of negative energies before entering the sacred Temescal. One by one the participants are cleansed and kneel down before the door to enter the lodge. “Amentekiasi” is whispered in the native Yaqui tongue, a word that pays homage to all spirits and asks permission for entrance. “Ajo” I hear from the leader in response, and, granted admission, I crawl into the dark space.

The dome is black as a moonless night, the air thick with anticipation. The last of the participants enter, moving in the clockwise direction, as is tradition, along the wall of the sweat lodge. The Guerreras, female warriors, form the outer circle of the Temescal, while the Guerreros, male warriors, make up the inner circle closest to the rock pit. Nervous chatter comes from one corner, but it quickly dissolves as Coyote declares the Temescal ready for the first seven rocks.

Hombre de Fuego appears with a pitchfork containing the first hot rock of the evening. “Bienvenida Abuelita”, -“Welcome Grandmother”- we cry out in unison as we stare in awe at the fiery glow of the rock in the doorway. The stones placed in the lodge are believed to be our ancestors -the grandfathers and grandmothers- who enter the Temescal to share with us their energy and wisdom. Coyote scoops up the rock with deer antlers, the traditional method for handling the stones, and carefully deposits it in the center of the pit. He produces a small beaded leather pouch containing the Myrrh and Copal resins and sprinkles them over the rock. Little stars spark as the herbs hit the heated stone, diffusing a sweet fragrance in the air.

Rock after rock is brought into the Temescal, some large, others small. Some are easy to handle, while others put up a mischievous struggle as they slip and slide out of the leader’s grip. The fourth rock seems to take on the form of an animal with piercing eyes, and the group shudders with excitement.

The seventh rock is finally in place. Hombre de Fuego delivers the bucket of water infused with sage and closes the door. We now find ourselves sitting cross-legged in a dark earthen den, returned to our mother’s womb. The group needs to adapt to the dark and confining space so Coyote allows us a few minutes to acclimate.

Luisa, an older woman and newcomer to the Temescal, begins to panic. I hear her praying in a frightened but hushed voice while her companion murmurs words of comfort to her. I sympathize, this is not an ideal setting for claustrophobics. Immersed in the darkness, senses deprived, thoughts from deep within surface and self-examination is inevitable.

She regains her composure and prepares to surrender to the new experience that awaits her. Coyote senses her resolve and resumes with his task. Speaking in Spanish, he breaks the silence with slow and deliberate words, branding us with their significance: “Welcome to the Temescal ceremony, a Native American tradition existing for centuries. The objective is to purify ourselves physically, emotionally, and spiritually, and to be freed of old habits that impede our growth. Inside the Temescal we reconnect with our innate wisdom, and improve our clarity of thought and intuition. It’s the time to seek answers, to state intentions, and to be reborn into the world with awareness and purpose. It’s the time to be a warrior.”

Our leader pauses for a moment and stirs the water with a wooden spoon. He dips a cup into the cool liquid and holds it above the rocks, a silent prayer on his lips. He pours the water over the stones, releasing clouds of vapor into the air. The steam quickly permeates all parts of the lodge, and what began as a cool, crisp room has swiftly turned into a sauna. I inhale quietly, focusing on calming my heartbeat as my body tries to deal with this sudden assault of hot air.

The traditional sweat lodge ceremony consists of four rounds, or “doors”. Each represents one of the four directions and its associated element: the first door is symbolic for the East and air, the second the West and water, the third the North and earth, and the fourth the South and fire. Each element represents human qualities that are meditated on by the participant during the sweat: air stands for thought and communication, while water is the realm of dreams and intuition. Earth keeps us grounded and nourished, while fire fuels us with passion and determination.

When the participants reach their limit, and the unanimous decision to open the tarp door is made, the round ends. In between the doors, when the tarp is lifted, Hombre de Fuego adds seven more rocks to the lodge, making for an increasingly hotter space as the evening progresses.

Drumming, rattling, singing, meditating and storytelling are all part of the Temescal experience. The intense heat, the steam, the darkness, and the chanting are elements that contribute to the charged atmosphere and propel the participants into somewhat of an altered state. Each door ceremony is conducted differently according to the energy present in the lodge. Lasting anywhere from ten minutes to an hour, some rounds are warm and pleasant while others are blisteringly hot.

The first two doors were warm and tolerable, introducing us gently into an evening of purification. Still, a steady stream of participants left after the second round, mostly first-timers having sampled the experience and in no rush to push their limit. The third door presented more of a challenge and we lost much of our initial group when the tarp lifted. Even Temescal veterans considered their work done and opted against the fourth round. As for myself, curious to see how much I could stand, I stayed for the last round.

The fourth and final door closes. The sweat lodge now contains twenty-eight rocks, seven of which are fresh out of the fire. Only a few people remain to endure the door of the south, represented by the element of fire. This round is believed to burn away any last impurity in the body.

All that can be heard is the continual pouring of water over the rocks, creating billowing clouds of steam so hot that I flinch when they reach my face. I lower my head to rest it between my knees and wrap my arms tightly around my legs. I struggle to stay calm. My body begs for the cool of the outdoors, but I resolve to stay strong and focused.

Many of the participants have begun pressing their bodies to the ground, allowing for as much of their skin to feel the cool earth, the last mass to heat up in the sweat lodge. I follow suit. Although I’ve decided to surrender to the process, I have no desire to pass out.

The heat is unbearable and I feel dangerously close to losing consciousness. It is difficult to breathe and I hear another participant gasping for air. My lungs are burning. In desperation I lower my lips to the ground and inhale whatever cool air is left. Any advice I’ve ever heard on how to manage the stifling heat of the lodge fails to work for me now. “Mind over matter” is useless counsel when my body is boiling. I’m ready for Coyote to end the round.

Finally the door opens. The menacing heat floats out of the hut, and I welcome the cooling breeze. My body slowly but surely adjusts, and after a while I lift myself onto my hands and knees and crawl to the door. I bow my head down in respect, and touch my forehead to the earth. “Permiso para salir”, -“permission to leave”- I whisper. I emerge from the Temescal drenched from head to toe, wearing drooping clothes sodden with steam and sweat. I stand still, too weary to move, and gratefully let the cool night air envelope me.

I gradually open my eyes and allow them to adjust to the fire, still crackling and glowing. People bundled up in thick clothes rest by the warmth, quietly discussing the night’s events. I glance up at the moon, our muse, and wordlessly pay my respects.

As though not wanting to break a spell, I tiptoe quietly to the two large barrels of sage water behind the structure. I grab a bucket and rinse myself, washing away the physical residue of the experience. But the night is cold on my skin, and I hurry back to my car for a fresh change of clothes. Warm and dry, I return to the fire and join the others still basking in the afterglow of the ritual.

I walk over to Hombre de Fuego, still diligently feeding the fire to keep us warm. I catch his attention, a difficult task since his focus is the flame. As I thank him for his hard work, I marvel at the fact that he is only a boy of 15, very young for the honored position of fire-keeper. I note the AC/DC rock band T-shirt he’s wearing, another indication of the subtle merging of the old tradition with the modern world.

I leave Hombre De Fuego and stride over to Coyote. He’s the last to leave the sweat lodge, relishing in those few precious moments of solitude with the Temescal and its spirits. I express my gratitude, and he smiles and nods. I go back to the warmth of the fire and enjoy some quiet time to digest the experience.

The challenges I faced tonight are the same I confront most times when I enter the Temescal. Although difficult and uncomfortable at times, the result is totally worth it. The sweat lodge is a rite of passage where I increase my endurance, strength and courage; qualities I arm myself with for the battles I fight in the fast paced city I live in.

As I’m reflecting on the event, Kachorita, the Shaman’s youngest son, begins singing an old native song. In a forgotten language and a haunting voice, he tells the tale of his people, ancient stories of Native American creation and tradition. I join in with my rattle and revel in the sweet music of the past. I’m honored to be part of something so ancient and pure, and after the Temescal ceremony I feel like a warrior, ready to face the challenges of the other world.

How would one find this lodge if they wanted to participate?

I would like to go to one of this spritaul lodges, and meditate. I live in California could any one provide me a location if the have one.