Young people paraded through the village plaza, singing and dancing. In large letters against a white background their banner proclaimed: Las Fiestas Taurinas, Los Ingenios, Diciembre 17, Sabado, 2:00 P.M.

Most bystander heads swung their way, proving the effectiveness of Mexican-style public announcements. All this hoopla guaranteed that somewhere, a good time was coming soon. Las Fiestas Taurinas. What was this all about? And for that matter, where in the world was Los Ingenios?

My husband, Bill, our teen-age daughter Rose, and myself were staying near Barra de Navidad, Jalisco. The small Mexican beach town nestles on the south end of a sweeping bay between Puerto Vallarta and Manzanillo. In 1993 Bill had driven the family van and trailer from Powell River, British Columbia to camp in this beautiful part of Mexico. Since that trip we’d enjoyed many annual vacations exploring familiar and new places, meeting old and making new friends.

One of our friends was Laura Simpson. She and I met last year over the Internet, when she’d written to say she enjoyed my stories. It turns out that our hometowns face each across the Strait of Georgia, which separates Vancouver Island from the mainland of British Columbia. So we arranged to rendezvous during the Christmas holidays near Barra de Navidad.

A Mexican friend disclosed that fiestas taurinas are community parties with rodeo style events which span several days. Bull riding mixes with robust quantities of dancing and drinking. Sounded good to me. Mexicans know how to party.

Los Ingenios turned out to be a tiny hamlet located somewhere north of Barra. Saturday around noon Bill, Rose and I hooked up with Laura and her friend, Suzanne. Bill hailed a cab and the five of us crammed in. The cabby said he could find Los Ingenios, about fifteen miles north and six miles east off Hwy. 200. After twenty minutes of twisting highway, he turned abruptly onto a dirt road. The cab slowed to a crawl. It swayed and jolted riotously with the roughness of the road, cut between palm trees, banana plants, and scrub jungle. Cattle periodically grazed in small clearings.

Finally, the road opened into a clearing ringed by a few modest dwellings.Unfolding cramped limbs, we climbed out of the car and stood beside a large aluminum-roofed palapa. After being paid, the cabby asked if he should return for us later.

Too quickly, I replied, “No, gracias, Señor.”

Denied a sure return fare, the cabbie frowned as he turned his car back towards town. But who knew when this fiesta would end? Besides, it was hard to imagine the party ending before it even began. I tossed the future glibly into the great mañana!

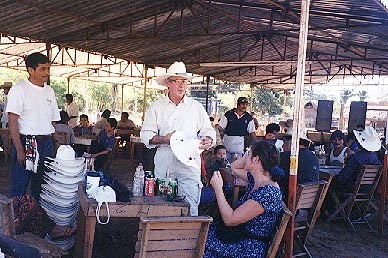

At 2:00 p.m. a dozen cowboy-hatted men sat among a mix of wooden tables and folding chairs. Music blasted from huge speakers at the far end of the palapa. A mixed scent of flora and dung hung in the air like rich incense. We picked a table farthest from the music and close to an improvised bar. A small waiter, as wiry as a fence, materialized on the spot. Deftly he downloaded five half-size bottles of beer onto the table.

“That’s fast!” I thought, savoring the sharply gratifying bitter thrust of that first taste.

Fourteen-year-old brown eyes lit up, “May I have a baby beer too? May I?”

“There’s probably plenty of pop around somewhere,” I answered, shifting Rose’s gaze towards the large blue cooler near the bar. Emilío Martinez caught my glance and approached our table.

I ordered, “Refresco, por favor. Fanta?”

With a nod of his head, he went for a cold pop. Rose relishes the fact that kids can go anywhere with their parents in Mexico. She’s been going everywhere since she was six. These days she loves playing pool and disco-dancing with her friends. She beamed as Emilío, the genie- waiter, whisked each empty bottle away, replacing it with a fresh drink.

A man approached Bill. He spoke behind a tall stack of new cowboy hats. “Sombrero, Señor?”

“Well…I’ve never worn a cowboy hat before but…why not?”

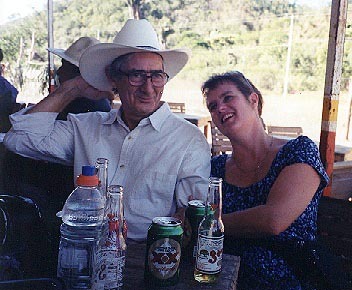

After trying on eight hats, Bill chose a cream-colored sombrero with a feather. The hat, perched on his graying hair, matched his light colored shirt and cargo pants perfectly. Bill looked like a gentleman rancher out on the town.

“How do I look, ladies?”

Rose’s face drained. “Buy one of those, Dad. And I die!”

“Then die, Darling!”

“I can’t believe you guys are my parents! You’re always bringing me to strange places and doing weird stuff.”

True. Parents naturally bruise teenage sensibilities, and we are no exception.

Mexicans began packing the palapa. A growing hive of babies, children, adults and old folks buzzed around us. Jeans, plaid work shirts and cream-colored cowboy hats identified dozens of rancheros. There were plenty of cowboys, but where was the rodeo?

Not far from our table, two rustically-thatched huts sagged beside a stick-and-wire fence. The huts didn’t even have a roof and the fence wouldn’t hold in a calf. Where was the real rodeo ring?

Interrupting my thoughts, Laura whispered, “Do you see a baño anywhere?”

I pointed to one of the palm-thatched huts. “You may be looking at them!”

Laura turned to Suzanne, “Want to check it out?”

Seconds later, as they scooted back, Laura murmured, “Only a hole in the ground. No privacy.”

Meanwhile the volume of the party cranked several notches higher. About a hundred people sat, talking, laughing and drinking. A shiny black truck thundered up behind the bar. Holding a loaded gun across his knees, a police officer stared stone-faced from the back of the truck box. Without a change of expression, he climbed out to join the two other officers at a table, obviously reserved for them. As straight as gun-decorated posts, three mouths quaffed beer while eyes trained on the surrounding party.

As the greasy roar of old engines died behind the bar, waiters strolled up to two old pick-ups. From the truck boxes, they started unloading ten huge earthenware pots. At the same time, the truck doors flew open and eight pairs of fashionable shoes stepped cautiously onto the dirt. Four middle-aged women picked their way towards a large empty table. Gold hoop earrings glittered below carefully coifed hair. Necklaces adorned smooth skin above pretty dresses. Artful make-up and immaculate manicured fingernails fairly shouted to the crowd: Glamour!

I mused on this word derived from the ancient Greek word ‘grammar.’ Originally the word meant a magic spell. The ladies certainly spread an aura of elegance over the event. Their badges identified them as hostesses for the Municipio de Cihuatlán, the seat of local government located about forty miles north. With great efficiency they began directing a bevy of younger beauties to serve food from the huge pots. Emilío socialized while he waiting in the long serving queue.

Leaning forward in her chair, Laura tilted her head towards me. “See those ladies that just arrived? They’re SO done-up! I feel underdressed! At least you’re wearing a dress! Got any make-up I can borrow?”

Unzipping my fanny pack, I rummaged for a lone tube of lipstick and compact mirror. Laura dabbed her lips generously and gave them a fruity smack. I burst out laughing. Laura’s bright lips exclaimed, “I’ve not worn lipstick for ages!”

Then grinning like a grown-up party doll, she added, “How do I look, guys? I’d have worn a skirt if I’d known the rodeo was going to be a fancy party like this!”

Receiving his bowls, Emilío delivered them to his nearest customers. Ten minutes later, he plopped three large bowls on our table. Laura prodded the contents. Fist size chunks of beef swam in a steaming broth. Hunks of cartilage and fat clung to pieces of leg bones.

“How we going to eat this?” she queried.

Suzanne’s eyebrows arched and she grimaced. “I’m a vegetarian. I can’t eat this! Anyone see a store around here?”

I poked a finger in the broth and sucked it. “It’s tasty! But I saw a small tienda towards the south end of this corral.”

Rose jumped from her seat, grabbing her purse. “Suzanne! I’ll go with you.”

Surveying my bowl, I gulped, considering, “Who was it that said all food is good food when you are hungry?” Had they ever eaten something that looked like this? But seven hours past breakfast, I could eat a cow – raw!

Later I learned that this kind of meat stew is called birria. This hearty meal, long on meat and short on vegetables, is a common Mexican dish. Restaurants dedicated to serving it are called birrerias. Bill and I had frequented one in Cihuatlan where three goats stood tied to a post in the back, awaiting their fate.

On his next pass, Emilío unloaded a stack of warm corn tortillas and a generous wad of servilletas. His third pass solved the eating problem when he plunked down several big spoons. Bill, Laura and I tucked in.

Belly full, I began chatting up my nearest neighbor in my best Spanish. After introducing myself, I asked Emundo Alvarez, “When does the rodeo begin? We’ve been waiting for two hours.”

With a smile like a half-moon, the burly man replied, “Mañanaaaaa! ”

“Oh! And when exactly do we pay for all the beer and food?”

“Later. This is a recibímiento (welcoming party). You pay only at the charreada (rodeo). I think maybe a dollar each. But first we must dance. ”

As I translated this information to the others, Emundo turned his broad- shoulders towards his wife, offering his hand. Touching it lightly, she rose beside her mountain of a man. They were the first couple to dance. Emundo’s hips rippled bonelessly. His arms, swelled like a medium-sized sumo wrestler’s, gathered his woman into his chest as they waltzed. They looked great.

I nudged Bill, “Please. Invite Laura to dance. She’s looking so beeeeautiful. Can’t let that lipstick go to waste!”

He invited Laura to dance. She never got another chance to sit down. Young boys of eight or nine tripped over each other, asking her to dance. The young men lined up for Rose. Several more couples began dancing. Bill and I joined them. Fiesta time!

Now it was 4:30 p.m. Pockets of people got up from the tables and moved towards the road. We’d been at the recibímiento for nearly three hours. Maybe it was rodeo time now. But I hoped not. Now that we were dancing, I felt a little reluctant to give up a party in a palapa for a rodeo in the bush.

However, after one more song our group left the palapa and drifted along the road with the crowd. A quarter mile later, a long table blocked the road. We paid a dollar each and walked on. A new rodeo ring appeared. Posts as thick as tree trunks held up a fence of heavy rough timber. Laura pointed to the people roosting on the top board twelve-feet up.

“You want to climb up there?” she queried.

“I don’t think so,” I said remembering my long skirt. “How about sitting on this bench?”

We squeezed into the last vacancy on the narrow bench circling the rodeo ring. Laura’s face softened, “You know what I like best about Mexico? It’s so social! Here we are in the middle of nowhere, with a hundred people we don’t know, and it feels like a big family party.”

I shook my head in agreement, ” I love it too.”

Indeed it felt exhilarating to be part of a healthy crowd with hearts beating in a community pulse. Mexico always reminds me how as humans we are naturally wired to be open to the world and each other, a fact easily forgotten within a gringo-fortified mentality. Whenever possible, I try to maintain my common sense but drop my habitual defenses. Genuine shared moments abound in Mexico. It seems that the people thrive on social contact.

All of a sudden, a van parked behind us. Teenagers unloaded piles of sound equipment including grand stereo speakers. If loud music at the recibímiento tortured eardrums, could they now be ruptured? We moved to the other side of the rodeo ring.

There Emundo and his family of five occupied a stretch of bench. Empty packs of beer lay scattered over a remaining space. I inquired, “Please, Sir. May we sit here?”

With a sweep of his bear paw, the beer cans tumbled to the ground. Another sardine squeeze onto the seat. Crackling overhead, a loudspeaker bawled out the next event. A bull blasted from the chute. Clinging bareback by a thin rope, a young ranchero jerked like a rag- doll astride the bucking beast. A few more mighty jumps and the guy flew through the air, hitting the dust. The crowd gasped as he scrambled clear of gouging horns. Six mounted rancheros threw lassoes trying to catch the bull’s hind hooves. When one lasso tripped the bull, he thundered to the ground. A ranchero jumped off his horse, swiftly untying the belly rope. The bull rolled over, struggling to his feet. Waving lassoes overhead the rancheros drove him back into the bullpen.

Three bucking bulls later, it was 5:30. Rays from the fading sun highlighted the honey-colored boards of the rodeo ring. The thick pale- green spiny fronds of the palms rattled like snakes in the warm breeze. Bill glanced up at the western sky.

“It’ll be dark soon. Better head back towards Barra.”

Rose and I hugged Laura and Suzanne good-bye. They’d heard that a dance followed the rodeo. Laura’s husband and another friend had arrived to keep the ladies company. Plus the four of them were staying close by that night. In the field parking lot, cars stood still. Time to starting hoofing it back towards Hwy 200. Five minutes later, a battered pick-up careened behind us. I jumped off the road and flagged it down. Expatriate Philip Bennett screeched to a stop.

“Are you going towards Barra de Navidad?” I asked.

Phil’s mouth moved hard and fast, like he drove his truck, “Yes, Ma’m. I’m heading for the bank machine in Melaque. Ladies up front!”

Bill scowled in my direction but crawled into the pick-up box, before he noticed no tailgate! His shouts were lost with the popping and grinding of gears as Phil tore up the bumpy road. A pale-white Rose gripped the door handle.

I begged, “PLEEEEESE. Slow down. My husband’s clinging for dear life back there.”

“HELL! What’s HIS problem?”

“He retired last month. He wants to live!”

Maybe a chord of mercy rang in Phil’s reckless soul because he slowed down—–a little. Record-breaking minutes later, the lights of Barra twinkled in the distance. By the time the truck stopped, Bill’s tan had nearly disappeared.

He bellowed, “I need a cigarette! And don’t ever ask me to do that again!”

I grinned weakly, “Sorry. I just gave them to the guy for the ride.”

There are more stories to tell about rides in pick-up trucks, taxis and buses in Mexico. Charreadas or rodeo-style shows are common throughout Mexico. Skilled club competitions are held most Sundays in the grand rings or lienzos of cities like Guadalajara. Most small towns and villages run local rodeo rings. Fiesta rodeos, like the one today, typically feature live bands, singers, dancing and even bullfighting clowns. Later when I described our experience to a friend raised in the area, he exclaimed, “A recibímiento! I haven’t heard of one of those in years! It used to be the tradition in the countryside for someone to host a dinner and dance for the whole community. It was a way of expressing gratitude to God and one’s friends and neighbours. Maybe the tradition is reviving.”

Gratitude flooded my heart anew at our discovery of a recibímiento — where looking and feeling good is always in style.

This is part 2 of 5

- Introduction to the Series

- Part 1: Charreada in Guadalajara

- Part 2: Receiving End of a Mexican Rodeo (Recibímiento á Las Fiestas Taurinas)

- Part 3: The Bullfight and Cantinflas

- Part 4: Cantinflas, the Castillo and Ponche in the Plaza

- Part 5: Gold Trail to Santa María del Oro, Nayarit

Published or Updated on: January 1, 2001