The first traces of an awakening sun touch the morning horizon, brushing aside the night’s long shadows. On the streets of Ixtapalapa, a working class neighborhood 30 minutes by cab from the center of Mexico City, young men – some in the dress of the Jerusalem of 2000 years ago – shuffle by hurriedly. Many are carrying huge crosses, some weighing as much as 200 pounds. They are headed for Cerro de la Estrella, the Hill of the Star. It is Good Friday of Holy Week, Semana Santa.

Gerardo Granados Juarez, the man they will call Jesus today, studies the colors of the sky over the hill. “It is beautiful,” he says.

This is his day, his time. It is at the Hill of the Star that Granados Juarez, chosen from hundreds who have asked to take on the coveted role of Jesus, will be “crucified.”

More than 4000 local residents act out other key roles in Ixtapalapa’s Semana Santa and Representacion de la Pasion, a dramatization that’s been played out on its gray, trash-strewn streets and around its decaying buildings, every year since 1843. In contrast the Passion Play in the German village of Oberammergau, is performed on a huge, tidy stage once every ten years.

Ixtapalapa, once a flourishing Aztec town, is normally not the destination of tourists. It is known more for the crime and poverty that plagues it and the swelling shantytowns that choke its fringes. Yet during Semana Santa more than 2 million people – mostly Mexican but with a scattering of Americans and Europeans – flock to it.

Semana Santa is widely celebrated throughout predominantly Catholic Mexico. All of the reenactments are dramatic and emotionally charged.

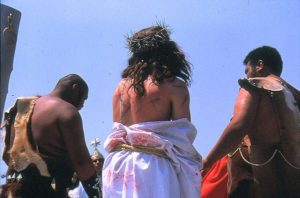

In Ixtapalapa a real crown of thorns is placed on the head of the actor portraying Jesus and thorny boughs are used to lash and whip him.

On Palm Sunday, villagers of Tehuilotepec lead a donkey carrying an image of Christ into Taxco, an old silver mining town. On Holy Thursday, thousands of the Catholic faithful bring hundreds of pets and caged birds to the baroque Iglesia Santa Prisca to greet a wooden statue depicting Christ at prayer in the Garden of Gethsemane.

In Patzcuaro, in the central state of Michoacan, the devout parade behind a Jesus whose face is painted black, and on Easter Sunday in San Miguel de Allende, pilgrims burn and explode images of Judas. Mexico City’s Templo de San Francisco El Grande is on Madero Avenue, a five minute walk from the city’s main plaza. There, during Holy Week, worshippers pray at the feet of a purple-robed, life-sized papier mache figure of Christ. Some come into the church shuffling on their knees. They bless themselves repeatedly, light candles, kiss the sash or hem of the robe and touch it to their eyes and lips.

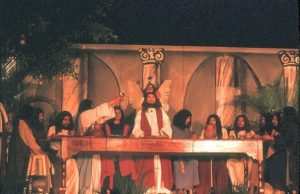

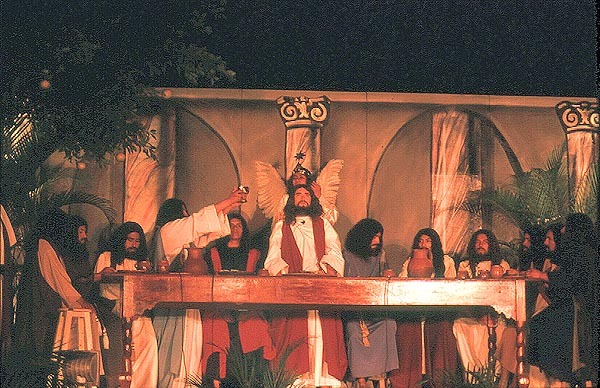

Semana Santa in Ixtapalapa begins with the celebration of Palm Sunday (Domingo de Ramos), commemorating Christ’s triumphal entry into Jerusalem. The Last Supper is staged on Holy Thursday (El Jueves Santo), and on Good Friday (El Viernes Santo), his sentencing before Pontius Pilate, and, finally, his crucifixion at Cerro de la Estrella.

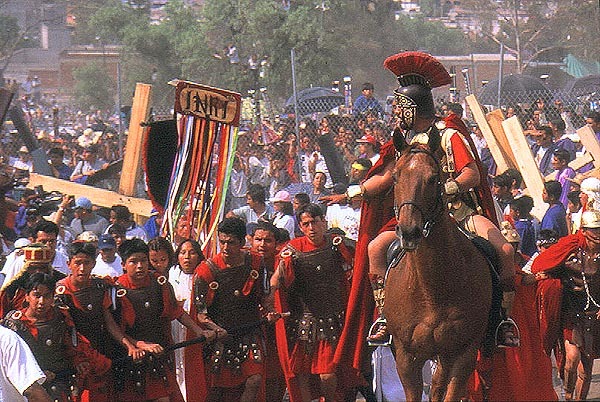

Those reenacting the events are dressed the way people did in Biblical times. They portray soldiers on horseback, magistrates in chariots, military commanders, centurions and praetorian guards in full Roman regalia, trumpeters, tympanists, citizens. Some of the men wear Old Testament beards.

All the biblical characters are here: Mary, mother of Jesus, Joseph, Mary Magdalene, the former prostitute whom Christ forgave and saved from stoning. So are all the Apostles, and Judas Iscariot, who betrayed Jesus. Herod and his court of women are here, too, and so is Barabas. He is the robber and insurrectionist who had been sentenced to crucifixion only to be freed after Pontius Pilate gave in to an angry mob demanding freedom for Barabas in exchange for the crucifixion of Christ.

On Good Friday in the main square, Pontius Pilate has sentenced Jesus to be crucified and orders him taken to a whipping post to be lashed by a pair of WWF look-alikes. It is then that Jesus begins his last journey to the Hill of the Star. The way of the cross is a mile-and-a-quarter of narrow, winding and sometimes cobble stoned streets coursing through eight barrios (neighborhoods). A thousand or so tunic-clad “Nazarenes” follow him, carrying their own crosses, some larger than his, some smaller. Many are wearing crowns of thorns. There are six and seven-year-olds weighed down by child-size crosses. Angelica Ramos is helping her seven-year-old son, Miguel, with his.

Barefooted and black-hooded penitents shuffle through the streets beating their backs with short whips, the ends of them fitted with balls of leather.

Jesus is wearing a crown of thorns. His face is twisted with pain, his feet are dirty, bruised and bloodied. A rope has been tied around his neck. A soldier pulls on it. Jesus’ legs wobble. He strains to stand tall but the weigh of the cross pushes him down. Simon of Syria, the apostle who forced the soldiers to help Jesus carry his cross, comes forward to help him. Jesus is lashed again. He gasps and moans and so do the people nearest him. They bless themselves. Many weep openly.

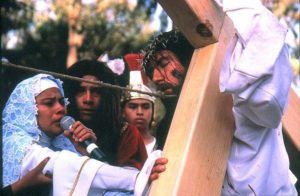

Enrique Vaquero, a small, dark curly-haired man in his 40s, shivers as each lash strikes the flesh of the man called Jesus. “Are you all right?” I ask him. “Yes,” he says, but I feel the pain, too.” Photographers and television cameramen push their lenses closer to Jesus. There’s a thick blood-like blob on the side of his face. Mary Magdalene has a microphone in her hand. Maybe it’s so that what she’s saying to Jesus can be heard by the thousands pushing in on them in the Plaza de Iglesia Cuevita. But the sound system is terrible – the volume is cranked up too high. Mary Magdalene has practically got the microphone in her mouth, and everything she’s saying is garbled. Next to me, Patricia del Castillo strains to hear. But no one, except maybe those perhaps within five feet of her, can make out what it might be. It’s like MTV doing a line on-stage interview with a rocker in the middle of a head banging heavy metal concert.

On Ermita Ixtapalapa, the main street, thousands of vendors are shouting as loudly as they can: ” dies (10) pesos, veinte (20) pesos.” They’re selling miniature crosses and Christ and Virgin Mary statuettes of wood, ceramic and plastic. Huge, brightly colored murals of the holy ones, painted especially for Semana Santa, brood over vendor stands overflowing with beaded rosaries, blood-streaked faces of Christ on white kerchiefs and Elvis-style velvet portraits of Christ and the Virgin Mary.

A carnival is at the edge of the vendor stands. There are car rides, train rides and rides on Ferris wheels for the kiddies. Hawkers try hustling moms and dads toward scales to guess their weight for five pesos. Eager, hopeful boys and girls throw rings made of plastic or rope around hoops for a prize that may come with their efforts.

Music blares from loud speakers. Frank Sinatra’s voice reaches over the masses singing something about one for my baby and one more for the road. Mothers with umbrellas protect themselves and their children from the hot sun. Men riding triciclistas fitted with cargo platforms in front, wheel sodas and water from vendor stand to vendor stand.

“Look at all this,” said Victor Serrano. “There was a time when all this was different. It was more respectful. No more. Now it’s like a party, a carnival.” He shrugged and walked on with his son. There are more of the devout than of the partygoers. The backs of the devout are to the carnival. Their ears are closed to the shouting vendors and the reverberating music of the mariachi.

On the cobble stoned streets of the Way of the Cross, Jesus takes the cross off his shoulder to rest. He is bent over from the weight of it. A soldier strikes out with his whip, but hits only the edge of the cross. “Veronica” pushes her way through the crowds to wipe the blood from Jesus’ face.

Ahead of him, a dozen or so horse-mounted Roman soldiers are pushing their way through the crowds sending spectators scrambling for the sidelines. Overhead, helicopters from the local television stations kick up swirls of dust as they circle the Hill of the Star for footage for the evening news telecast. Dozens of on-lookers hold handkerchiefs over their mouths to keep out the dust.

Near the top of the Hill of the Star, the apostle Judas Iscariot, who betrayed Jesus for 30 pieces of gold, “hangs” himself in a small cluster of trees close to where Jesus will be crucified.

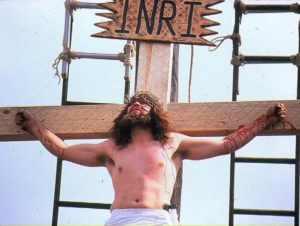

The moment has come. Jesus is at the top of the hill surrounded by soldiers beating him with sticks. When they are done they nail him to the cross, they hoist him and the cross until it is upright between the crucified criminals, Dimas and Gestas.

The head of Jesus is bowed. Blood streaks down his face and body. There’s no way to count the number of people there on the hill or near it, but it is easily in the hundreds of thousands. Everyone is shoulder to shoulder and back to front. Few speak.

They are all looking up at the sad, pained figure of Jesus on the cross on the peak of the dusty hill.

Many are crying without shame or embarrassment. All of them pray and bless themselves: ” en el nombre del Padre, del Hijo, y del Espiritu Santo (in the name of the Father, the Son and the Holy Ghost). “Why are we like this?” Antonio Rojas Rosas asks. “We pray, we cry, as if all this is real. But we know it is not. We know all this is only a reenactment. We know that.”

“But yet…..” he pauses, then adds: “I don’t know, maybe we come because we are all sinners. Maybe somehow it helps us make fewer sins in our lives.” He starts to walk away, hesitates a moment, his eyes reflective, his voice lower now. Then looking up again at the figure on the cross, he said: “Maybe, just maybe, people are better because of it.”