On a balmy summer evening in August 1940, a young man gained admittance to the study of Leon Trotsky’s heavily guarded house near Mexico City. He asked Trotsky to read something he had written. While Trotsky was poring over his article, the visitor removed an alpine climbing axe from his overcoat and sank it into the great thinker’s skull.

The assassin, who called himself Jacson Mornard, was traveling with a forged Canadian passport and claimed to be in Mexico on business. In reality, he was a Stalinist agent who had been posing as the boyfriend of Trotsky’s personal secretary in order to carry out his mission.

Joseph Stalin had expelled Trotsky from Russia in 1929 for relentless criticism of his dictatorial regime and its corruption of Marxist ideals. For almost a decade, Trotsky was doomed to wander from country to country – Turkey, France, and Norway – under constant pressure from Stalinist elements. However, he continued speaking out in letters, essays and books, including his Diary in Exile and his monumental three-volume History of the Russian Revolution.

Finally, in 1936 Trotsky was granted asylum in Mexico and settled in Coyoacán on the outskirts of Mexico City. At the time, Mexico had a strong Communist party, but it, too, was divided into volatile Stalinist and anti-Stalinist factions. In the middle of this political hotbed, the aging revolutionary and his wife of many years, Natalia Sedova, established their first real home since leaving the Soviet Union.

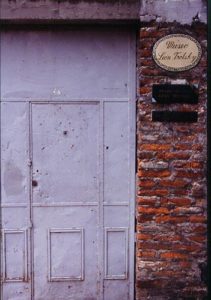

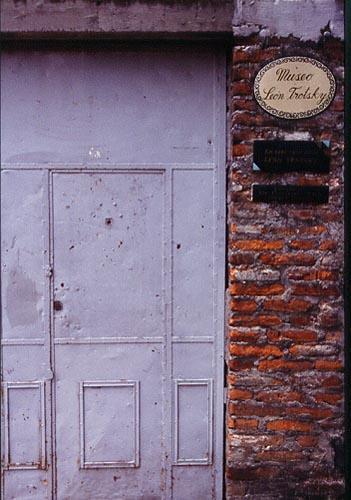

The house in which they spent most of their life together in Mexico still stands on a peaceful, tree-lined street a few blocks from Coyoacán’s main plaza, and is now a museum maintained by a non-profit organization that helps other political dissidents seeking asylum in Mexico. Behind its high stone walls and steel shutters, an intriguing slice of 20th-century history has been preserved for all to see.

Elegant Coyoacán has always attracted Mexico’s artistic and intellectual elite. In the 1930s, it was a provincial town surrounded by small farms and adobe hovels. Since then Coyoacán has been devoured by sprawling Mexico City, but its graceful plazas, colonial churches, and quiet cobblestone streets remain.

“The little fortress,” as Trotsky’s house is often called, has seen its share of violence. Bullet holes left over from an assassination attempt in May 1940 still scar the walls and thick front door.

Mexican painter David Alfaro Siqueiros and his gang of Stalinist thugs, disguised as police officers, overpowered guards and set up machine guns in the house’s inner courtyard, then proceeded to riddle its rooms with bullets. The Trotskys somehow managed to find a corner in their bedroom not in the line of fire. Their grandson, Seva, was wounded in the barrage, but miraculously no one was killed.

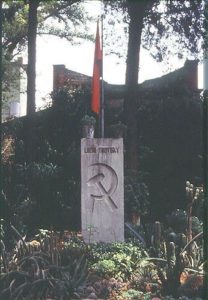

These days, the tranquil courtyard brims with tropical flowers and plants, including rare cacti which Trotsky enjoyed collecting on his excursions into the Mexican countryside. Vacant rabbit hutches and chicken coops border the walls, and a stone monument engraved with a hammer and sickle marks the spot where Trotsky’s ashes are interred. The red Soviet flag hangs limply from a pole above his tomb.

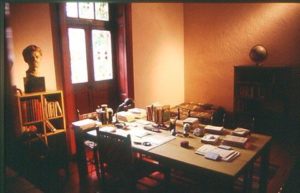

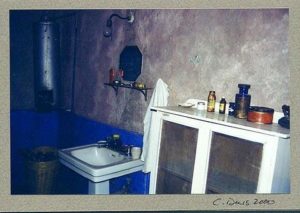

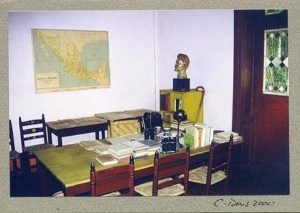

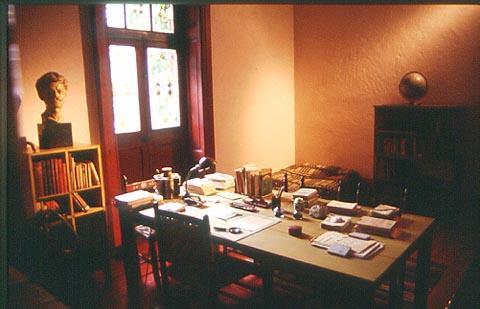

The interior of the house is austere and somewhat gloomy, as befits a fortress. However, great care has been taken to keep things the way they were during Trotsky’s time. In the narrow bedrooms, clothing and shoes are neatly arranged beside chaste beds, tattered Mexican rugs lay on the floors, and bullet holes pockmark the walls. Sunlight pours through open metal shutters into Trotsky’s study, bathing the desk at which he sat when struck down.

His trademark wire-rimmed eyeglasses which must have fallen off during the struggle still rest on the desk top, along with papers, pens, ink pots and a magnifying glass. An ancient looking dictaphone sits nearby, and a faded map of Mexico hangs on the wall. Well worn books on philosophy, history and political theory cram bookcases scattered about the room.

In what were once guest quarters at the end of the garden, hang dozens of black and white photos of Trotsky and Natalia accompanied by celebrated friends, such as the revolutionary Mexican muralist Diego Rivera and his artist wife Frida Kahlo.

Rivera, a founder of the Mexican Communist party, used his influence to help Trotsky gain asylum in Mexico. The two remained comrades until 1938 when they split over ideological differences and rumors of an affair between Trotsky and Kahlo.

There are also pictures of a contented Trotsky tending his rabbits and picnicking in the stark Mexican hills. One ominous snapshot shows him foraging for cacti with a pickaxe slung over his shoulder.

A new wing adjacent to the original house displays more photographs, newspaper clippings, and personal effects. Trotsky’s archives are here as well, along with a souvenir shop, and a gallery featuring works by Latin American artists. In spite of these modern additions, the house retains an air of authenticity. It is easy to imagine Trotsky’s ghost still haunting its lonely compound and somber halls.

Upon receiving the fatal axe blow, Trotsky did not topple over, but stood up straight and bristling like one of his stubborn cacti. He let out a piercing scream and then pelted his attacker with everything in sight, including his dictaphone, refusing to let him continue the assault.

Mornard was soon overcome by security guards, and when Natalia came running to her husband’s side, Trotsky turned his bloody face toward her and said calmly, “Now it is done.” The tension had finally been broken. Years of waiting for the inevitable were over.

An ambulance rushed Trotsky to hospital where he remained lucid while nurses prepared him for the operating table. After his operation, he fell into a coma and died peacefully the next night (August 21, 1940) with Natalia by his bedside.

The police arrested and interrogated “Jacson Mornard.” He insisted his name was Jacques Mornard Vandendrechd and claimed to be the son of a Belgian ambassador. However, his true identity was later established as Ramon Mercador, a Spanish Communist.

The courts convicted Mercador of premeditated murder and he served 20 years in Mexican jails. Upon his release in 1960, Mercador reportedly fled to Prague and then Moscow where he was awarded the Order of Lenin. According to some reports, he eventually died of cancer in Havana.

GETTING THERE:

Coyoacán is easily reached from downtown Mexico City by taxi or on Line 3 of the inexpensive and efficient Metro (subway). The Museo Leon Trotsky is located at Viena 45, about seven blocks northeast of the Plaza Hidalgo in central Coyoacán. Opening hours are Tuesday to Sunday from 10 am to 5 pm. Admission is about US $1.00. Telephone 5-554-06-87.