She is the mother of all Mexicans, the savior and succor of the indigenous spirit, protectress of the poor, dark, ailing and humble. She is the Dark Madonna of Indian features, who appeared just after the invasion by the white-skinned Europeans. She is miraculous and comforting, the emotional support to a conquered nation, orphaned from their pantheon of gods and spirits of nature.

Today, across the country, the shrines to her are numberless. Her images smile behind glass in saloons, gleam on tin in the kitchen, hang in taxis, and are carved into cradle-boards. They are fashioned in plaster, marble, wood, stone, clay, cake, candy, cloth, tissue-paper, beads and embroidery. Her figure adorned the flag of Don Miguel Hidalgo, father of the movement for Independence. She was declared Empress of America by a Papal Bull in 1754. Pope Leo XII crowned her Queen of the Mexican people in 1895. The title Celestial Patron of Latin America was given to her in 1910. And in 1945, she was crowned queen of Wisdom and of the Americas. Named Patron Saint of the Americas by Pope John Paul II, she is a beloved manifestation of the Catholic faith.

Every city in Mexico has a church consecrated to her name. Near the place of her appearance, north of Mexico City, is the original Basilica of Guadalupe (completed in 1709 and holding, according to tradition, the original tilma (a rectangle of muslin worn as a cape) of Juan Diego) next to the huge modern church built in 1976. There is a shrine at the very place of her apparition, and a well, decorated in talavera tiles, holds the miraculous waters of the spring that gushed forth at her feet. At this place, and at all the churches with her name, thousands of the faithful gather on December 11th and 12th, to give tribute to her, to petition for a miracle, or to give thanks for one already received.

In Oaxaca, on the eve of the feast of the Virgen of Guadalupe, babies and toddlers are dressed in representation of the many Indian tribes of Mexico. The procession begins at La Catedral on the zócalo and fills the streets, accompanied by singing and punctuated by firecrackers. It ends at her church on the Llano Park, for the mass of thanksgiving for her protection and grace.

On the following day, the children are brought again. In the hot Mexican sun, blue-black hair gleams, deep facial shadows contrast with brilliant highlights on the copper skin of children. Colored ribbons in the babies’ hair and strands of glass beads glisten and shine. The children are patient, as they wait in the long line to pass through the church, to leave their baskets of roses or poinsettias, to light the candles and to pray. They sometimes fuss when their parents rearrange the tilmas or re-paint their smudged moustaches. But they seem to understand that this is an important affair, and quietly wait their turn to revere the Holy Mother.

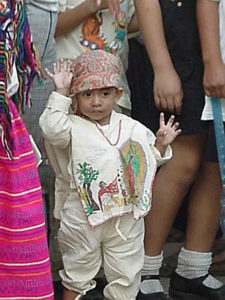

Costumes of all kinds reflect the variety of Mexican traditions. As in other human clothing, the females have more choices in finery. The boys are usually dressed in white muslin, red belts and huaraches. The brims of their woven palm hats are turned up in the front, framing a paper image of the Virgin. This arrangement gives them an endearing, slightly comical look. The moustache drawn on with eyebrow pencil transforms the round-faced baby into Juan Diego. On the tilma the image of Guadalupe appears as she did on the cloth of Juan Diego, centuries ago. Some of the youngsters carry a costalito, equipped with a forehead strap and decorated with miniature articles like a petate and kitchen instruments, necessary for a long pilgrimage. They will bring offerings of flowers, the poinsettia of the season, or roses like the ones Guadalupe sent to the bishop, as proof of her apparition.

While most boys are in white, you will meet the occasional charro (Mexican cowboy) with his huge hat, flashy bandana, and silver coins down the sides of his pant-legs. But the little girls steal the show. From the tiniest baby to the most demure teenager, each one is delightful. The traditional costume is a puff-sleeved embroidered blouse, multicoloured rebozo and a gathered flowered skirt. They wear strands of brightly coloured beads and long braids (often made from dark yarn, ingeniously attached to their shorter hair) and carry baskets of flowers. But especially in Oaxaca, with its 16 official ethnic groups, the costumes are varied. You can see little Tehuanas, Yalaltecas, Mazatecas, a rebozo gracefully wrapping the head, wearing huipiles, both sumptuous and austere.

Of course, it’s not all serious. The Llano Park is taken over by secular pleasures as well — mechanical rides, marble-rolling for prizes, and balloons that manage to dodge the menacing darts, for that elusive plaster eagle or authentic image of Pokeman. Oh, and the food! Children delight in the flavoured ices, popsicles, cups of gelatines and cotton candy; and the smells of little fried gorditas Guadalupanas, and all the other antojitos of Oaxacan cuisine fill the air.

And then, the commemorative photograph. Not as common in years past, nowadays the ingenuity for photo-ops is delightful. They will pose the children on the traditional burro, dressed up with crepe paper and flowers with the image of the virgin up on top. If sitting on a burro is too distressing for the little one, there are peaceful grottoes, with the figure of Juan Diego kneeling before the Blessed Mother, that can serve as a background. The mujercitas demonstrate crushing corn on a metate (look up at the camera and smile, mi hija), or cooking the tortillas on the comal. (First let’s straighten up the bows, and braids to the front, please.)

Mexicans adore their children. They are their delights, each one a gift from heaven. On December 12th, Mexicans celebrate their spiritual indigenous roots by bringing them to the Virgin of Guadalupe. She sees all of the nation, rich and poor, exalted and humble, as her children, and holds them in her protective grace.

The Appearance of Guadalupe

The story goes like this.

In 1531, a scant ten years after the fall of the Aztec nation, a humble Indian named Juan Diego was walking over the hills just north of Mexico City (built on the razed Azctec capital of Tenochtitlan). Land there is dry and rocky, favoring only cactus and lizards under a blistering sun. He passed by the hill of Tepeyac, once the site of the temple to Tonantzín, the gentle goddess of earth and corn, whose name means “our mother.” The conquering Spaniards had destroyed this and most of the other sacred places of the indigenous people, forbidding them to pray to their protecting spirits. They were spiritual orphans then, not yet embracing, as foster-mother, the Catholic church. They had to hide small idols and talismans, to worship and pray in secret.

As he passed this once-revered place, Juan Diego stopped and stood still, disbelieving the heavenly fragrance and celestial music that surrounded the spot. Before him shone a radiance, like a glowing cloud surrounded by rainbows. Then the blessed Mother Mary emerged, robed in blue and gold and rose. She calmed his fears, calling him “little son,” and urging him to return to the city and request the bishop to build a shrine to her, on the very place of the fallen goddess.

Of course the bishop did not believe the peasant and sent him on his way. Ashamed that he had failed her bidding, he avoided the spot, passing the next day on the other side of the hill. But she was not to be denied. She found him and urged him once again. It was not until the third time she appeared to him, that she sent proof of this miracle. She told Juan Diego to pick the Castillian roses, impossible to exist in that climate, but growing in abundance on that place. He gathered them in his tilma, a rectangle of muslin worn as a cape. She told him not to put them down until he was in the presence of the church dignitary. When he did this, in the cathedral of Tlatelolco, they saw that the front of his tilma was emblazoned with the image of the Virgin of Guadalupe and the miraculous blossoms lay at her feet.

The Dark Madonna was immediately embraced by the indigenous people, and other miracles quickly followed, in which floods and pestilence were overcome and the personal prayers and needs of her many believers were answered. The symbols of her miraculous presence are the Castillian roses found in the desert and Juan Diego’s tilma bearing her image.