Porfirio Santiago is at his loom, diligently weaving a massive 2 x 3 meter rug with traditional designs, from memory, with representations of Zapotec diamonds, rainfall, maize and mountains… just as his father Tomás, grandfather Ildefonso and great grandfather before him. Wife Gloria is carding a mix of white and caramel colored raw wool. Behind them, hanging over the black wrought iron banister overlooking the sunny open courtyard are drying batches of spun wool in tones of green, brown, red and blue, byproducts of the use of natural dyes from the añil or indigo plant, seed pods, mosses, pecan, pomegranate zest, and of course the cochineal bug.

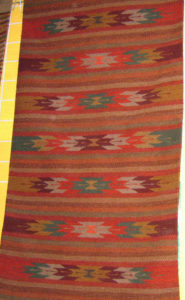

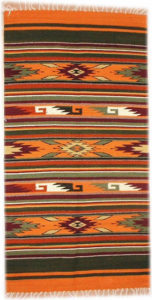

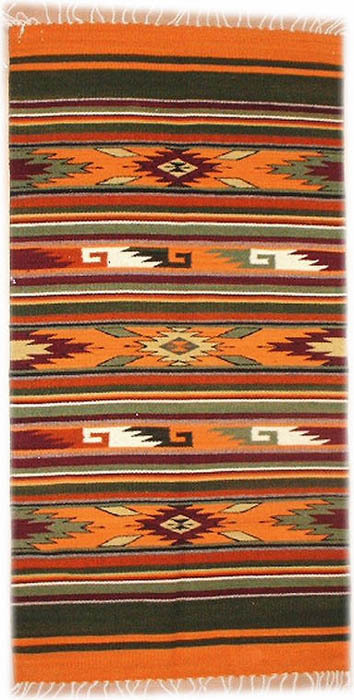

Such ritual in Teotitlán del Valle, an ancient tribal town about a half hour’s drive from Oaxaca, has been played out continuously on a daily basis since about 1535, when Dominican bishop Juan López de Zárate arrived in the village and introduced borregos (caprine sheeplike animals yielding wool) and the first loom, shipped from Spain across the Atlantic. The use of natural dyes and weaving predate the conquest, but it was the European invasion which jump-started a cottage industry producing sarapes, blankets and tapetes (rugs).

Over generations the village grew, and began specializing in solely rugs, initially used as trade and sale items within a commercial network of towns in other parts of the state and, to a lesser extent, other regions of the country. With the completion of the pan-American highway connecting Oaxaca with Mexico City in the late 1940s, the market opened up. By the 1950s, air travel had begun to facilitate greater export as well as a tourist industry, which quickly took notice of a broad range of handcrafted items from foreign lands.

Artesanías Casa Santiago is comprised of a single extended family whose main production facility, showroom and homestead has been on the town’s main street since 1966. Then Porfirio occupied most of his working hours as a campesino in the fields, with rug production as a sideline. Over the decades, he began spending fewer days working the land and more producing tapetes of both traditional Zapotec designs, and, more recently based upon consumer demand, of modern patterns, reproducing themes from the masters of modern art and accepting custom orders such as the recent request for a wall hanging promoting Pentax cameras.

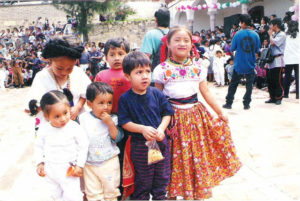

Illustrative of the depth of this family tradition, five of Porfirio’s six siblings and their families are weavers, the other is a pre-school teacher. On Gloria’s side, while her siblings are members of a large well-known musical band that plays at municipal fiestas, weddings, quince anos and other rites of passage, they too are trade artisans, although more on a part-time basis. All of Porfirio and Gloria’s children work in the industry, as do their spouses. Three of four sons and their wives live on premises and work at all phases of production, with the fourth having his own taller just up the street. One son, Omar, is an architect, but is nevertheless an integral contributor to all aspects of the family business. One daughter and her husband work at the main facility, another is employed at her in-laws’ workshop and restaurant a couple of blocks away, while the last and her husband have their own home and rug business.

Porfirio Santiago adjusts the warp on his wide two-heddle handloom. The master weaver creates stunning Zapotec rugs in his Teotitlan del Valle workshop in Oaxaca. © William Ing, 2007

Porfirio Santiago adjusts the warp on his wide two-heddle handloom. The master weaver creates stunning Zapotec rugs in his Teotitlan del Valle workshop in Oaxaca. © William Ing, 2007

Each child completed high school, deciding to thereafter keep the family tradition alive to the extent possible. As has been repeating for generations, the grandchildren – now 17 in number – while watching their parents and grandparents from infancy, begin learning in earnest at about 10 years of age, and by roughly 20 are proficient at all aspects of the operation. In terms of the division of labor, years ago women tended to dye, card and spin, while the men were the weavers. Nowadays, at least in this family, each is fully capable of performing all tasks, although it’s exclusively men who work the largest looms requiring the greater strength and stamina.

Another family convention has been the performing of important administrative duties for the town without monetary compensation, an aspect of voluntary community labor known as tequio. In 1931, Porfirio’s grandfather was mayor of the village and, more recently between 1996 and 1998, Porfirio himself was el presidente municipal (mayor). By then the job had become a three-year unpaid post, nevertheless requiring a full-time commitment, necessitating doing the farming, raising family and maintaining a rug business in the early morning hours or after dark. Yet the pride and sense of responsibility in serving one’s community took priority over concerns about being able to get all the work done in 24 hours that had to be completed. Even today, on a seasonal basis, Porfirio splits his time between making and selling woolen products, and working the fields to supply the family with corn for tortillas and tamales.

Despite being one of the most personable families one could ever hope to happen upon in the Valley of Oaxaca, Don Porfirio et al. don’t get the large tour buses stopping by their shop for exhibitions. Perhaps it’s the personalities of the family members that clearly don’t lend themselves to the formality of onlookers seated in a gallery for a demonstration, followed by a hard sell. Maria Luisa and husband José Luis, Tomás, Hugo, and the rest of the family on hand seem to have learned from their parents to be more relaxed and engaging within a congenial informal setting. They’ll take you to see whatever galvanized metal, plastic or clay pots happen to be in use for dyeing, and bring over a simple cardboard box to show you a half dozen or so natural substances used for coloring the wool. If Gloria isn’t available to card and spin, perhaps a daughter-in-law will shyly say that she’ll do it, smiling as she admits she’ll not as good at is as her suegra (mother-in-law). It’s a more real and honest attempt to demonstrate the way things are actually done in the Santiago family, not at all contrived, and absent any pretension whatsoever. It’s what drew me and my wife to Casa Santiago in 1993, for the purchase of our first tapete that even today continues to enhance our living-room floor. It draws us back time and again for a visit, often with a spur-of-the-moment offer of a little mescal with a botana, either alone, with friends and family visiting from Canada and the U.S., or with touring clients.

While over time Casa Santiago has succeeded in adapting to changing domestic and international trends in terms of color tones and combinations, designs and diversity of product (now also offering handbags, wall hangings, pillow covers and more), it’s the longstanding, proud Zapotec custom of producing tightly woven, high quality traditional rugs that will live on through Porfirio, Gloria and their lineage.

Artesanías Casa Santiago, Av. Juarez 70, Teotitlán del Valle, Oaxaca 70420. Tel: 52 (951) 524-4154; 52 (951) 524-4183. Web: https://www.artesaniascasasantiago.com.

Alvin Starkman together with wife Arlene operates Casa Machaya Oaxaca Bed & Breakfast. Alvin received his masters in social anthropology in 1978, and his law degree in 1984. Thereafter he was a litigator in Toronto until taking early retirement. He and his family were frequent visitors to Oaxaca between 1991 and when they became permanent residents in 2004. In his spare time Alvin leads private, small group tours to the craft villages, towns on their market days, ruins and other sites; writes articles about life and cultural traditions in Oaxaca; translates from Spanish to English for a local newspaper; and writes a legal column for a Canadian national antiques newspaper.