From many streets away, we could hear the band playing the distinctive music. It was Carnival in Tepoztlán, and the Chinelos were dancing. We headed in the direction of the music to a small clearing outside the entrance to the church where children, dressed in spectacular costumes and wearing bearded masks, were jumping and hopping around in a circle. The band played in that slightly off-key, repetitive beat so evocative of Mexican village life and so mesmerizing. The festive atmosphere drew me in and I too joined the crowd in the endless procession. This was my first introduction to the Chinelo dancers of Morelos and ever since I have been fascinated with this colorful spectacle.

The role of a Chinelo dancer is handed down through the family, and those children in Tepoztlán were being taught by their parents so they could carry on a tradition. Their fathers performed the day before, completely covered in their elaborate but suffocatingly hot costumes: the same repetitive steps for hours on end.

The dance itself is called the brincon or jump, and the choreography is exceedingly simple. With feet apart and knees slightly bent, the dancers take two shuffling steps, and then leading with their shoulder, take a little jump to the left or the right. Around and around the plaza they go. People join in and drop out but the troop continues to dance, while the band plays on. It is easy; it is monotonous; it is hypnotic; and it’s fun. This could well be the original hip-hop. Most Chinelos are young men – one needs to be young as this is tiring. After two hours, the band and the dancers change but the dance itself continues, sometimes into the early hours of the morning.

Chinelo dancing is always accompanied by a brass band. Live music is an essential part of every Mexican festivity and the local brass band is an integral part of every Mexican community. They play at festivals, weddings, funerals and rodeos. Like the Chinelo groups, band positions are handed down from father to son, and these days sometimes father to daughter.

The Chinelo dancers are now a symbol of the state of Morelos. Traditionally dances start the last weekend of January and different towns take turns on successive weekends until Carnival and the commencement of Lent. (In 2001, Lent begins on Wednesday, February 28).

The dance itself has its origins in pre-Hispanic rituals. At the time of the conversion of the Indians to Christianity, many native ceremonies and traditions were incorporated into the local Christian rites.

Accustomed to it in their old religion, the Indians were greatly attracted to pomp, and of all the peoples of Europe, the Spaniards were, by temperament and experience, the most fitted to supply it. The processions not only marched into and around the atrio, they often developed into dances there. The natives might not wear their old costumes or secret emblems, sing their old songs, or dance at night or in the church itself; but they were allowed to dance in the patio after Christian feasts if the proposed performance was approved.

Carnival, the four days of freedom prior to Ash Wednesday and Lent (40 days of general abstinence) was one of those “approved” times. The Carnival tradition of wearing masks, role reversal, anonymity, and general license to misbehave is still common throughout the Catholic world.

In this region, sometime during the colonial period one of these dances developed into a mockery of the Spanish and other Europeans with their fine clothing, beards, fair skin and arrogant manner.

From the mid 19th century until the early 20th century the dance costume began to take on the form that we see today. The elaborate dress, gloved hands, uptilted beard and arrogant stance makes a mockery of the salon dancing so beloved of the upper classes during the period of the French intervention (1864 – 1867) under the hapless Hapsburg Emperor Maximilian and his Empress Carlotta. Later attempts at the “Europeanization” of Mexico came under the dictator Porfiro Díaz whose autocratic rule from 1877 to 1910 attempted to modernize Mexico by force. Old movies from the turn of the century show society women dressed in broad feathered hats and elaborate gowns brought from Paris. Men sported waxed beards and heavily decorated military uniforms and plumed helmets, modeled closely on European designs.

During this period Morelos was one of the richest states in the nation due the production of sugar, which found its way to eager European markets. The Sugar Haciendas were worlds unto themselves: great luxury for the (often absentee) owners and misery, debt and poverty for the workers. Repressed and exploited, it’s small wonder the campesinos (peasants) resorted to making a mockery of their repressors. In 1910 the lid on this situation blew and the Mexican revolution began, led in the south by a peasant from Morelos; the charismatic Emiliano Zapata, who no doubt would have seen these satirical dances performed in village festivals.

The state of Morelos (just south of Mexico City, bordering the Federal District) is part of the old Aztec world. The Aztecs divided their cities and towns into capullis or wards each with its own temple, community hall and social organization. In Mexico today, community life still centers around both the parish and the municipality. Traditional ceremonies, with their pre-Hispanic roots, are usually still organized at the parish level. Four large municipalities in the state, which have been continuously occupied since pre-conquest days, are famous for their Chinelo Dance Troops: Talayacapan, Tepoztl án and Yuatepec to the west and Juitepec which is just south of the capital, Cuernavaca.

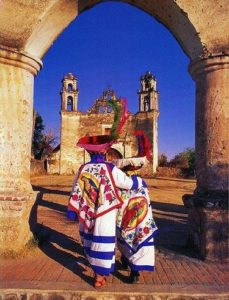

The town of Tlayacapan is probably where the modern format for Chinelo dancing originated. Tlayacapan was mentioned by both Cortes and Bernal Diaz del Castillo as a settlement they encountered on their march to take Cuahnahuac (modern day Cuernavaca), prior to the fall of Tenochtitlán in 1521. The town clings to its rich heritage and is famous for its pottery, candle making, bands and, of course, its Chinelo troop. It also has an extraordinary number of churches, the largest being San Juan de Bautisto an ex-Augustinian monastery with a simple, but grand facade and large atrio. Chinelos did and still do perform in the church atrio during Carnival.

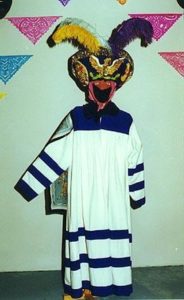

The Chinelos of Tlayacapan wear a much simpler costume, closer to its origins. The hat is broader, less embellished and has only two or three plumes. The “dress” or tunic is a simple robe of white and blue with no other embroidery. A patterned bandana is tied around the head under the hat. Across the shoulders is a drape, so that from the back view one can see a picture of Our Lady of Guadalupe: Mexico’s Patron Saint.

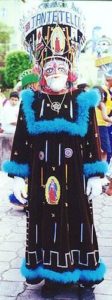

In time, the costume began to change. The nearby town of Tepoztlán developed its own attire and stylization began. The hat gradually changed shape becoming higher, straighter and more elaborate. In Tepoztlán the tunic is made of black velvet and embroidered with sequins. I have seen photographs of Chinelo dancers dating back to pre-revolutionary times (prior to 1910). Between then and later photos taken in the 1930’s, one can see a distinctive change in the style of the hat with more elaborate embroidery on the costumes.

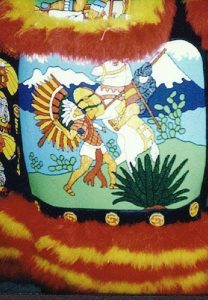

Now each town and dance troop has its own distinctive costume. Hats are richly beaded with pre-Hispanic images and modern interpretations of ancient legends. These dancers are from Yuatepec. Note how the costume (Image, below, right) has developed: the huge hat, the number of feathers and the amount of “fur” on the costume. The hat is festooned with beads and baubles. The lower panels of the tunic (both front and back) feature beaded pictures depicting pre-Hispanic motifs and stories.

This example (Image below) from the lower back panel portrays an Aztec warrior battling a conquistador on horseback. A maguey plant is in the foreground and a nopal cactus at the back. The two volcanoes, Iztaccihuatl and Popocatepetl are in the background.

The Chinelo’s masks are made of mesh and always feature an upturned beard. The pale skin, fair beards and light eyes of the masks reveal the original targets of scorn. The dress-like feminine costume combined with the bearded masks gives the Chinelo’s a weirdly androgynous appearance: amusing yet disturbing.

Anonymity is another important element of the Chinelo persona. Perhaps it was originally to protect oneself in the face of later reprisals by Spanish overlords. It is nigh well impossible to identify individual Chinelos, apart from height or their shoes. They are completely covered and some even disguise their voices. A bandana covers the neck and chin. The mask is placed over this, then the hat. Gloves even hide an individual’s hands. To further assure anonymity, costumes are closely guarded and kept secret. Members of the troop dress in different houses to add to the confusion. Thus completely anonymous, young men could view prospective novias or girlfriends as they paraded around the Zocalo.

The cost of the elaborate costumes is high. There are professional costume designers, mask makers and beaders, and these men vie with each other to win the competitions, which are now held to judged the best costume. I once met a designer in Tepoztlan whose workshop was filled with fabric, beads, sequins; designs patterned on paper and Chinelo memorabilia. He showed me photographs of the Tepoztlán group dating back 70 years. His son was learning the trade from his father and is now a Chinelo dancer himself. When the son showed me a hat, I joked with him that next year I would know whom he was. “Oh no!” he said, “I will be wearing a different hat and a new costume. You won’t recognize me.”

Rather than a tradition that is dying out, Chinelos are increasing. More towns have dance troops and it is now possible to hire a group for a festival at times other than Carnival. Over the last 15 to 20 years, women have also joined in. Perhaps it’s the history surrounding the dance, or maybe its vibrancy in the face of encroaching non-Mexican culture, but locals are proud of this unique tradition and Chinelos have a fabulous following here in Morelos.

You can see Chinelo Dancers performing in Morelos during Carnival: the four days prior to Ash Wednesday, i.e. 24 – 27 February, 2001. I will be conducting day tours to Tlayacapan or Tepoztlán to see Chinelos perform and join in Carnival activities.

The author wishes to thank Salvador Melquiades Martínez for his assistance i preparing this article.

(Photographs courtesy CONACULTURA (Archivo Unidad Regional de Culturas Populares Morelos)