Did You Know…?

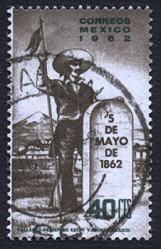

Of the many battles fought on Mexican soil in the nineteenth century, only one — the Battle of Puebla, fought on May 5, 1862 — has given rise to a Mexican day of national celebration.

Why this one? The main reason is that the Battle of Puebla marks Mexico’s only major military success since independence from Spain in 1821.

Other Mexconnect articles about Cinco de Mayo

- Cinco de Mayo: What is everybody celebrating?

- Cinco de Mayo celebrations in Mexico

- A Mexican menu for Cinco de Mayo

The story behind Cinco de Mayo

Mexico has never been considered a military power. In the nineteenth century, France, Spain, Britain and the U.S. all hatched or carried out plans to invade. Mexico’s nineteenth century history became a catalog of repeated “interventions” by foreign powers in its internal affairs.

The first French invasion, the so-called Pastry War in 1838, lasted only a few days. A decade later, U.S. troops entered Mexico City, and Mexico was forced to cede Texas, New Mexico and (Upper) California – in all, some 2 million square kilometers (half its territory) – in exchange for 15 million pesos.In 1857, Mexico proclaimed a new constitution. This incorporated the Ley Juárez (which established equality before the law) and the Ley Lerdo (which forced the sale of property owned, but not directly used by, the church or local governments).

The Reform War

This led to the Reform War (1858-60) between the liberals, led by Benito Juárez, who supported the new constitution, and the conservatives. The War decimated the country’s labor force, reduced economic development and cost a small fortune. Both sides had serious financial problems.

In the middle of the war (July 1859), Juárez (in Veracruz) published Reform laws, which nationalized church property and established the separation of Church and State. Later Reform laws established civil matrimonies and a civil registry, suppressed almost all religious festivities, and proclaimed the right to freedom of worship. Predictably, the liberals liked the Reform laws, the conservatives did not. Even as the conservatives were signing a treaty with Spain, the liberals were busy reaching an agreement with the U.S. In exchange for 4 million pesos, the U.S. would receive the “right of traffic” in perpetuity across the Isthmus of Tehuantepec. However, this treaty was never ratified by the U.S. Senate.The Reform War ended in 1860. Pro-liberal forces, led by General González Ortega, finally occupied Mexico City on Jan 1, 1861. The conservatives went into hiding, but would reappear shortly afterwards, supporting another French invasion.

Empty coffers; mounting debt

President Juárez took office to find that the public coffers were empty. He set about enacting the Reform laws, expelling several diplomats and some clerics, as well as trying to nationalize church estates. Resistance was stiff. Juárez believed that Reform would solve financial problems, and enable Mexico to pay off its foreign debt. It would allow communications to be improved and subsidize lucrative colonization projects, but the conservatives remained opposed, and Juárez had to continue to maintain a sizeable, and expensive, army. The national deficit approached 5 million pesos a year; foreign debt totaled 80 million pesos.

On July 17, 1861, the Juárez administration, desperate to avoid bankruptcy, decreed a suspension of all payments on its foreign debt for two years. The vote was approved by the Mexican Congress by a single vote.The foreign powers were furious. Three months later, Britain, France and Spain decided to jointly seize the port of Veracruz on Mexico’s Gulf coast and obtain payment by force. In December, 6,000 Spanish soldiers landed, joined a month later by 7,000 British marines and 2,000 French troops.At this point, France demanded that Mexico repay 12 million pesos, an absurdly large sum, and one well beyond Mexico’s means. Juárez negotiated and, satisfied that their demands would be met, England and Spain withdrew. France, however, had other ideas.

The French decide to stay

To understand their motivation for remaining, a little background is needed. France’s emperor, Napoleon III (Louis Napoleon Bonaparte) had grand ambitions. Urged on by his Spanish wife Eugénie, Napoleon envisaged French influence spreading throughout the Americas. He wanted to impose a monarchy, construct a canal and railway across the Isthmus of Tehuantepec, and limit U.S. expansionism. Some historians claim that Napoleon believed he could sweep aside the other fledgling Latin American republics and establish an empire stretching as far south as Tierra del Fuego.

To achieve these lofty ambitions, Napoleon needed a suitable puppet for the Mexican throne, and he had the perfect candidate: Austrian archduke Maximilian von Habsburg.The French troops had moved inland from Veracruz. While final details were being negotiated, the French had agreed to withdraw back to the coast, leaving only some sick soldiers behind in the healthier highlands. Instead, they occupied the city of Orizaba, and then routed a Mexican force which tried to hold the pass of Aculzingo.Mexico was unable to call on U.S. assistance, since the U.S. was then in the throws of its own Civil War. Abraham Lincoln was sympathetic, but not in a position to help.The French Army was supremely confident that they could crush any potential enemy militarily. Since tasting defeat at Waterloo in 1815, the French had won numerous victories in Europe and Asia, and were unbeaten in almost fifty years. The French Commander, Charles Ferdinand Latrille, the Count of Lorencez, went so far as to boast that:

“We are so superior to the Mexicans in race, organization, morality and devoted sentiments that I beg your excellency [the Minster of War] to inform the Emperor that as the head of 6,000 soldiers I am already master of Mexico.” 1

Mexican Resistance

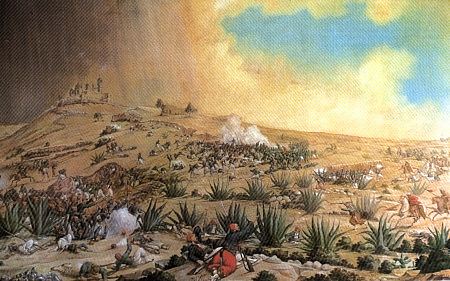

Marching towards Mexico City, the French needed to secure Puebla, now defended by 4,000 or so ill-equipped Mexican soldiers. Ironically, given the subsequent outcome, many of the defenders were armed with antiquated weapons that had done battle at Waterloo prior to being purchased in 1825 by Mexico’s ambassador to London at a bargain-basement price. The Mexican forces, the Ejército de Oriente (Army of the East) were commanded by General Ignacio Zaragoza, a Texas-born Mexican.

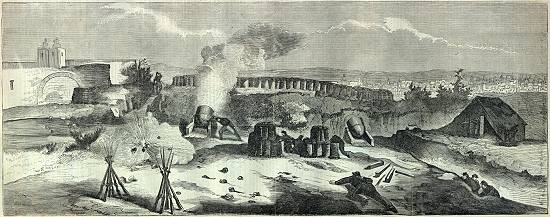

Fifteen years earlier, 30,000 Mexican troops, commanded by General Antonio López de Santa Anna, had failed to contain 6,000 U.S. soldiers under General Winfield Scott. The numbers facing each other at Puebla did not appear to hold out any hope for Zaragoza, who dug his forces into defensive positions centered on the twin forts of Loreto and Guadalupe.

The events of 5/05

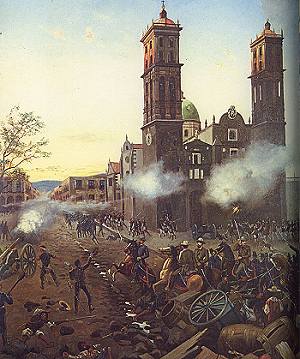

On the Cinco de Mayo (May 5th) 1862, Zaragoza ordered his commanders – Generals Felipe B. Berriozabal, Porfirio Díaz, Félix Díaz, Miguel Negrete and Francisco de Lamadrid – to repel the invaders at all costs.

leads his cavalry against the French.

The French launched a brief artillery bombardment, but then found that the uneven field where the fighting was taking lace had become so muddy from heavy unseasonable downpours that maneuvering their heavy weapons was very difficult.Bullets rained down on them from Mexican troops, who occupied the higher ground near the forts. At noon, the French commander, General Lorencez, ordered his troops to charge through the center of the Mexican lines. But his plan failed to work. The lines held strong, and musket fire began to take its toll. Two more determined French attacks were rebuffed.

Then the Mexican forces counter-attacked, spurred on by well organized cavalry, led by Porfirio Díaz, who would subsequently become President of Mexico.

As the afternoon wore on, and the smoke cleared, it became apparent that the defenders of Puebla had successfully repelled the European invaders. The French troops fled to Orizaba, where Zaragoza attacked again. This time, they scuttled back to the coast to regroup. A crack European army had been soundly defeated by a motley collection of machete-wielding peasants from the war-torn republic of Mexico…

On May 9, 1862, President Juárez declared that henceforth the Cinco de Mayo, the anniversary of the Battle of Puebla, was to be a national holiday.

Mexican infantry repels the French who flee, pursued by Mexican cavalry.

The French get reinforcements

Back in Paris, Napoleon was enraged. He ordered massive reinforcements and shortly afterwards, a 27,000 strong force of French military might arrived, determined to place Maximilian on the throne of Mexico.

In 1863, the strengthened French army (under Marshal Elie Forey) took Mexico City, forcing Benito Juárez and his supporters to flee. Juárez established himself in Paso del Norte (now Cd. Juárez) on the U.S. border, from where he continued to orchestrate resistance to the French presence.Supported by the conservatives, Maximilian finally ascended to the throne in May 1864. By this time, in the U.S., the Unionists had taken Vicksburg, and the U.S. government was considering its position. In May 1865, General Philip Sheridan led 50,000 U.S. soldiers to ensure that French troops did not cross the Mexico-U.S. border. Diplomatic pressure for a French withdrawal intensified. Napoleon III finally agreed to remove his troops in February 1866, and the last ones set sail back to Europe in March 1867.After the French left, President Juárez reestablished Republican government in Mexico, and put Maximilian on trial, ending an extraordinary period in Mexican history.

Significance of 5/05

Xalapa, 1981

With the passing of time, the Cinco de Mayo has assumed added significance because it marks the last time that any overseas power was the aggressor on North American soil. In Mexico, the Cinco de Mayo is still celebrated with lengthy parades in the state and city of Puebla, and in neighboring states like Veracruz. Numerous streets are called Cinco de Mayo; there is at least one in almost every town and city throughout the country.

In the U.S., the Cinco de Mayo has been transformed into a much more popular cultural event. Many communities use Cinco de Mayo as the perfect excuse for to celebrate everything Mexican: food, music, drinks, dancing, crafts and customs. The Cinco de Mayo has become not just a day in the calendar, but a very significant commercial event, one now celebrated much more north of the border than south of the border.

Where to go – Texas

General Ignacio Zaragoza died on September 8, 1862, only a few months after the Battle of Puebla. In 1960, the General Zaragoza State Historic Site was established in his birthplace, near Goliad, Texas, to commemorate his famous victory. In Zaragoza’s time, the town was known as La Bahía del Espíritu Santo.

General Ignacio Zaragoza died on September 8, 1862, only a few months after the Battle of Puebla. In 1960, the General Zaragoza State Historic Site was established in his birthplace, near Goliad, Texas, to commemorate his famous victory. In Zaragoza’s time, the town was known as La Bahía del Espíritu Santo.

Where to go – Puebla

The Guadalupe and Loreto forts are in parkland, about 2 km north-east of Puebla city center. The Fuerte de Guadalupe is ruined. The Fuerte de Loreto became state property in 1930. It is now a museum, the Museum of No Intervention ( Museo de la No Intervención), complete with toy soldiers. The park has an equestrian statue of General Zaragoza and is the setting for the Centro Civico 5 de Mayo, with its modern museums, including the Regional Museum (history and anthropology), the Natural History Museum and the Planetarium (IMAX screen).

In 2012, to mark the 150th Anniversary of the Battle of Puebla, a major re-enactment of the Battle was held in Puebla, attended by the President and many cabinet members and officials. A commemorative bi-metallic 10-peso coin was also issued to commemorate this anniversary. The re-enactment has since become an annual event.

Where to go – Mexico City

For Mexico City dwellers who don’t want to travel the short distance to Puebla, a longer-standing re-enactment has been held each year since the 1930s at Peñón de los Baños, a rocky outcrop close to Mexico City’s international airport. Of geographical and geological interest, the rocky outcrop of Peñón de los Baños was formerly an island in the middle of Lake Texcoco. The prominent landmark was visited by Alexander von Humboldt when he toured parts of Mexico in 1803-4. The re-enactment of the Battle of Puebla at Peñón de los Baños attracts tourists, history buffs, and Mexico City residents looking for an unusual experience.

Happy Cinco de Mayo!

Footnote

1 Quoted in “Betterment for Whom? The Reform Period: 1855-1875” by Paul Vanderwood, chapter 12 of The Oxford History of Mexico (ed by Michael C. Meyer and William H Beezley, O.U.P. 2000)

An updated version of this article is reprinted as Chapter 14 in the author’s Mexican Kaleidoscope: myths, mysteries and mystique (Sombrero Books, 2016).