Wendy Devlin

Most people think of piñatas as a fun activity for parties. The history of the piñata reveals many interesting facts that go beyond the playing of a game, although piñatas certainly have been intended for fun.

Piñatas may have originated in China. Marco Polo discovered the Chinese fashioning figures of cows, oxen or buffaloes, covered with colored paper and adorned with harnesses and trappings. Special colors traditionally greeted the New Year. When the mandarins knocked the figure hard with sticks of various colors, seeds spilled forth. After burning the remains, people gathered the ashes for good luck throughout the year.

When this custom passed into Europe in the 14th century, it adapted to the celebrations of Lent. The first Sunday became ‘Piñata Sunday’. The Italian word ‘pignatta’ means “fragile pot.” Originally, piñatas fashioned without a base resembled clay containers for carrying water. Some say this is the origin of the traditional pineapple shape. Also the Latin prefix ‘piña’ implies a cluster of flowers or fruits as in ‘pineapples’ and ‘pine cones’.

When the custom spread to Spain, the first Sunday in Lent became a fiesta called the ‘Dance of the Piñata’. The Spanish used a clay container called la olla, the Spanish word for pot. At first, la olla was not decorated. Later, ribbons, tinsel and fringed paper were added and wrapped around the pot.

At the beginning of the 16th century the Spanish missionaries to North America used the piñata to attract converts to their ceremonies. However indigenous peoples already had a similar tradition. To celebrate the birthday of the Aztec god of war, Huitzilopochtli, priests placed a clay pot on a pole in the temple at year’s end. Colorful feathers adorned the richly decorated pot, filled with tiny treasures.. When broken with a stick or club, the treasures fell to the feet of the god’s image as an offering. The Mayans, great lovers of sport played a game where the player’s eyes were covered while hitting a clay pot suspended by string. The missionaries ingeniously transformed these games for religious instruction. They covered the traditional pot with colored paper, giving it an extraordinary, perhaps fearful appearance.

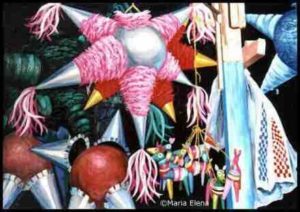

The decorated clay pot also called a cantero represents Satan who often wears an attractive mask to attract humanity. The most traditional style piñata looks a bit like Sputnik, with seven points, each with streamers. These cones represent the seven deadly sins, pecados – greed, gluttony, sloth, pride, envy, wrath and lust. Beautiful and bright, the piñata tempted. Candies and fruits inside represented the cantaros (temptations)of wealth and earthly pleasures.

Thus, the piñata reflected three theological virtues in the catequismo. (religious instruction or catechism)

The blindfolded participant represents the leading force in defying evil, ‘Fe’, faith, which must be blind. People gathered near the player and spun him around to confuse his sense of space. Sometimes the turns numbered thirty three in memory of the life of Christ. The voices of others cry out guidance:

¡Más arriba! More upwards!

¡Abajo! Lower!

¡Enfrente! In front!

Some call out engaños (deceits, or false directions) to disorient the hitter.

Secondly the piñata served as a symbol of ‘Esperanza’, Hope.

With the piñata hanging above their heads, people watched towards los cielos (sky or heaven) yearning and waiting for the prize. The stick for breaking the piñata symbolized virtue, as only good can overcome evil. Once broken, the candies and fruits represented the just reward for keeping faith.

Finally the piñata symbolized ‘Caridad’, Charity. With its eventual breaking, everyone shared in the divine blessings and gifts.

The moral of the piñata: all are justified through faith.

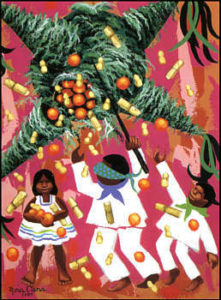

Today, the piñata has lost its religious symbolism and most participate in the game solely for fun. Piñatas are especially popular during Las Posadas, traditional processions ringing in the Christmas season and at birthday parties. During festivities, people traditionally sing songs while breaking the piñatas.

“Dale, dale, dale, no perdas el tino,

porque si lo perdes, pierdes el camino.

Esta piñata es de muchas mañas, sólo contiene naranjas y cañas.”

Hit, hit, hit.

Don’t lose your aim,

Because if you lose, you lose the road.

This piñata is much manna, only contains oranges and sugar cane.”

Another popular song for hitting the piñata is rooted in the year 1557 when dignitaries of Felipe II toured towns in New Spain. While exacting pledges of allegiance, coins of nickel were offered for coins of silver. This failed to please the people so as they break piñatas during las posadas, they sing:

“No quiero níquel ni quiero plata:

yo lo que quiero es romper la piñata.”

“I don’t want nickel/I don’t want silver

I only want to break the piñata…”

Piñatas can be found in all shapes and sizes. Modern ones often represent cartoon or other characters known to most children. Others are shaped like fruits, baskets, rockets etc. Sometimes people of political statue are satirized. At Christmas, star-shaped piñatas suggestive of the Star of Bethlehem are especially popular. One’s imagination is the creative limit.

Traditionally, piñatas are filled with both candies and fruits. Around Christmas in Mexico, wrapped candies, peanuts, guavas, oranges, jicamas(a sweet root vegetable), sugar cane, and tejocotes (a kind of crab apple) stuff piñatas. Some types of piñatas called traps, are stuffed with flour, confetti or ‘flowery water’. Any child without a treat after the goodies are gathered from the ground is given a little basket full of special candy. These colaciónes are kept on hand to avoid hurt feelings and tears. The rest of the treats are passed around to everyone before the party is over.

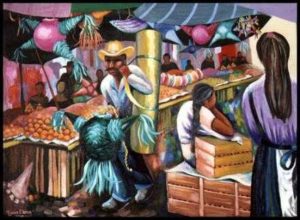

Towns of potters once existed to fashion ‘ ollas piñateras’, bare clay pots sold in the mercado. (market) People took them home and pasted their own colored paper to them. Cardboard and paper maché often fashioned over balloons has replaced ‘ la olla’ in many modern piñatas.

The piñata’s versatility contributes to its perennial popularity. Fashioned from a long tradition the joyous piñata continues to enchant celebrations and parties around the world.

In Mexico you will hear parents and children singing this special Piñata song.

“Dale, dale, dale, no pierdas el tino,

porque si lo pierdes, pierdes el camino.

Esta piñata es de muchas mañas, sólo contiene naranjas y cañas.”

La piñata tiene caca,

Tiene caca:

Cacahuates de a montón.

Esta piñata es de muchas mañas,

Sólo contiene naranjas y cañas.

No quiero oro, ni quiero plata,

Yo lo que quiero es romper la piñata.

Ándale Juana, no te dilates

Con la canasta de los cacahuates.

Anda María, sal del rincón

Con la canasta de la colación.

En esta posada nos hemos chasqueado

Porque Teresita nada nos ha dado.

Echen confites y canelones,

a los muchachos que son muy tragones.

Todos los muchachos rezaron con devoción,

De chochos y confites les dan ya su ración.

Castaña asada, piña cubierta;

Echen a palos a los de la puerta.

Ándale Juan, sal de la hornilla

Con la botella de la manzanilla.

De los cerritos y los cerrotes,

Saltan y brincan los tejocotes.

Andale niña, sal otra vez

Con la botella del vino jerez.

Esta posada le tocó a Carmela:

si no da nada le saco una muela.

Piñata Images Copyright © 1999 Maria Elena.

All Rights Reserved Worldwide.

https://mariaelena-art.hypermart.net

Related articles about parties and fiestas:

- A Piñata tradition

- Faith: the heart of Mexican fiestas

- La Quinceañera: A girl’s 15th birthday celebration is very special

Dates of fiestas, festivals and holidays:

Miscellaneous popular beliefs:

Published or Updated on: February 16, 2007 by Wendy Devlin © 2008

Love the creativity and thought they put in it also how the color and shape tell about the person and it’s thinking

I am a Chinese descendant and very surprised to learn the alleged Chinese origin of piñata, because it is completely absent in the New Year celebrations that we have been practicing to this day. I have done full text search in The Travels of Marco Polo but cannot find any record. Could you kindly point out the literature source of such claim?

Thanks for your valuable comment. Sorry, but we have no idea of the original source for this widely-held belief.

I have also never heard of the Marco Polo idea but a lot of sources are citing this article as proof of it. Could you please provide the citation for this “widely-held” belief please?