Exploring Mexico’s Artists and Artisans

In the late 1950s and early 1960s, the Mexican city of Cuernavaca served as the home of Russian American artist Ary Stillman, whose art was profoundly impacted by his stay there.

“As Ary said, in Mexico he felt ever more strongly the essence of the ‘inner reality,'” wrote the artist’s wife, Frances Fribourg Stillman, in the book Reminiscences.

An avid traveler, Stillman was first drawn to Mexico in 1940, nearly two decades before he would settle down in Cuernavaca. At this time, he was focused on representational artwork, as evidenced by the landscapes that he produced during his sojourn through Mexico.

“He had some beautiful scenes of cities, landmarks and the squares,” notes James Wechsler, Ph.D., who currently serves as curator at the Stillman-Lack Foundation. Among the 700 painting and drawings that Stillman bequeathed to this foundation that promotes and researches his art, there are approximately 15 pieces that were created during his 1940 trip to Mexico. Wechsler believes that the artist produced at least 25 oil paintings during the six-month journey, which included stops in Mexico City, Saltillo, Orizaba and Guanajuato.

“He probably painted outdoors, maybe on a portable easel, because I haven’t seen any sketches and they all look like they’re pretty quickly painted,” Wechsler notes. “Maybe he just set up his easel and did these very Impressionist-looking scenes of whatever it was he was looking at.”

In the same year he visited Mexico, Stillman himself remarked, “My work is based upon relationship of realities. I love to watch people – moving crowds fascinate me, play of light and the drama of life excite me to paint and to try to recreate in moving design the crystallization of the things seen.”

By the time Stillman returned to Mexico in 1957, his painting technique had changed considerably. This shift in his artistic style can be principally attributed to the outbreak and aftermath of the Second World War, which had an irrevocable effect on him.

“Right after World War II, like a lot of artists, he had this major revelation about mankind and cruelty,” Wechsler explains. “He basically stopped painting what was outside and started focusing on the inside, is the way he put it.”

Frances Stillman recounted this period of her husband’s life in Reminiscences, in which she described him as “profoundly shaken by the war.” She recalled conversations in which he said, “I cannot continue to paint the way I have been doing, I am sure that every creative person will have to make some change. For me, the world of surface realities is no longer paintable… I shall have to dig down deep within myself-back to my subconscious, if possible-and bring out what will be an inner reality.”

Thus, by 1946, Stillman had immersed himself in the New York art movement known as Abstract Expressionism, which resulted in a permanent departure from his former representational style. Stillman seemed particularly drawn to the Abstract Expressionists’ exploration of archetypal forms and symbols that are said to exist deep within the subconscious.

“With the very early kind of Abstract Expressionism in the late ’40s, artists started looking towards mythology and other cultures… and going back to what they called (a) ‘primitive’ ideal,” Wechsler explains. “I guess it was searching for some kind of purity (and) really getting away from the contemporary.”

When Stillman made his move to Mexico in 1957, he was in the midst of a deep depression and barely even painting. But slowly the artist returned to his work and this examination of the “primitive” ideal began to emerge again in his pieces, eventually evolving into a complex style that was entirely Stillman’s own.

The artist’s 1957 arrival in Mexico was markedly different from his first trip there nearly two decades earlier. He arrived in Cuernavaca as a despondent man, having suffered an eye hemorrhage that threatened to permanently distort his vision, lost his treasured studio in New York, and spent a year of disillusionment in Paris, which had once been his beloved home in the 1920s and early 1930s.

As Frances Stillman recalled in Reminiscences, after she and her husband settled in Mexico, “it was long before he began to paint. He seemed drained of all creative energy; once in awhile he would take up his brushes listlessly and try to paint, but there was nothing ready to bring forth.”

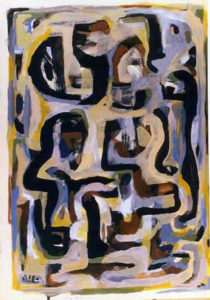

Gradually, however, artistic inspiration began to flow once again and Stillman was back in front of the easel a year after his arrival in Mexico. He started off painting in black and white, which Wechsler says was a natural progression from the charcoal series that Stillman created during his year-long stay in Paris. In addition, this high-contrast combination was easier for Stillman to work with than color, due to his damaged eye.

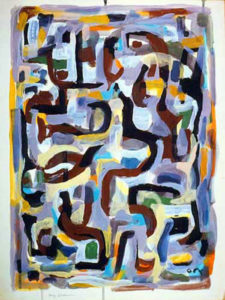

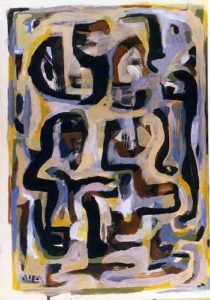

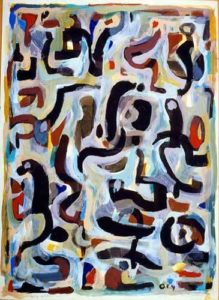

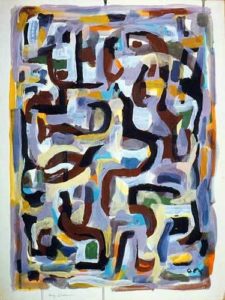

Little by little, the artist began to incorporate color into his pieces, which proved to be a turning point for him. During his remaining years in Mexico, he went on to produce more than 100 gouaches in a distinct style that melded the Abstract Expressionist technique with shards of Mexican mythology and a myriad of other elements that had influenced him throughout his lifetime.

“Cuernavaca worked a miracle on Ary,” noted Frances Stillman in Reminiscences. “Gradually, his health and eyesight improved and his painting seemed revitalized. For the next few years, there was an outpouring of fantasies on canvas or paper.”

Frances Stillman saw a marked change in her husband, who had even begun signing his pieces in a different manner, writing his first name in place of the “Stillman” signature that he had used for prior work.

“According to what his wife said, he came to the end of this very dark period and started producing all this intense work and signing it with just his first name, like as if he were a new person,” Wechsler notes. The curator believes that this rebirth of sorts may have also been influenced by the pre-Columbian philosophies that Stillman was pondering over at that point in his life.

“A lot of the pre-Columbian religions and mythologies… have to do with this idea of life being a cycle,” Wechsler explains. “Stillman read a lot about the Aztec and the Mayan cultures and maybe there was something to that also – this idea of a kind of rebirth and cyclical life, instead of living and dying and that is it in a linear way. Maybe as an older person, it was something he was thinking about.”

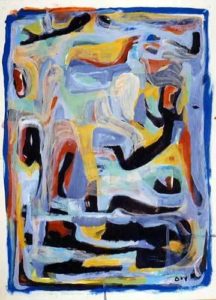

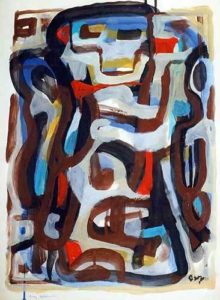

Pre-Columbian elements appear in much of Stillman’s work dating from his years in Mexico, as exemplified by the gouaches From an Aztec Temple and Sacrifice. As Wechsler points out, the abstract figure that dominates From an Aztec Temple is reminiscent of Cuatlique, the goddess of the Earth who was depicted by many pre-Columbian artisans as a fierce woman adorned with a necklace of human hearts and a skirt of writhing snakes.

“It’s abstract, so it’s hard to really pin it down, but the forms are there,” Wechsler explains. “I would say it is based on (Cuatlique).

As for Sacrifice, Wechsler sees a sacrificial altar, along with knives and drops of blood, among the abstract shapes.

This series of gouache on paper that includes From an Aztec Temple and Sacrifice has been hailed by various art critics as the apex of Stillman’s creative trajectory. Frances Stillman, who spent more than two decades observing her husband’s evolvement as an artist, described the gouaches as “the culmination, or at the least the beginning of the culmination of his entire career as a non-representational painter.”

Wechsler agrees with this description, calling the series “sophisticated” because of how Stillman meshed together his own childhood memories with cultural references dating back thousands of years.

“So often, an artist late in life really gets stuck in the style that he developed when he was younger and it’s rare that an artist changes and develops in such an extreme way towards the end of his life,” Wechsler notes. “I think (the gouaches) are really satisfying that way – to see someone who is approaching the end of his life, to have this burst of vitality like that.”

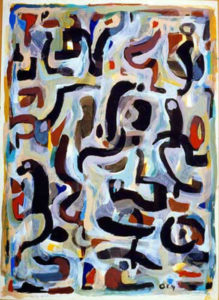

After completing more than 100 gouaches, Stillman began a series of acrylics entitled Leyendas, which marked a return to canvas for the artist. Acrylic, however, was a new medium for Stillman, who eschewed slow-drying oils in favor of this more rapidly drying paint. Its swift-drying quality allowed the artist to capture the spontaneous shapes that streamed forth from his subconscious in a manner that was not possibly with oils.

“More and more of his paintings flowed out of a dream world – these were not paintings that one brooded over – they poured out in a stream of consciousness,” Frances Stillman recalled in Reminiscences.

Even after his ailing health forced Stillman to relocate to Houston in the early 1960s, Mexico continued to hold sway over his mind and his work. Two years before his death in 1967, Stillman described his time in Mexico as “a period when fantasy became paintable, or when I invaded the world of fantasy. I was completely involved in the mysticism of the subconscious. This mysticism is the inner thing which gives the spark of imagination.”