“Does your husband ever carve nudes,” I asked Enedina Castillo Castillo, only half jokingly. She grinned up at me with those wise eyes.

“Once he carved a David that looked like the one by Miguel Angel,” she assured me.

“You mean the one in Italy,” I asked incredulously.

“Sí, the one with the hands.

“And the….”

“Sí, cierto, that one.”

I couldn´t even imagine how her husband, Eliseo Castillo, would know that Michelangelo sculpted a David, much less that he would try his own hand at carving the likeness of one with his little hand-forged knife.

By this time I think I had met nearly the entire Castillo family – although with so many people coming and going, it is hard to tell – and had lunch in their home in Tocuaro many times. This family never ceased to amaze me. I had to admit to myself one more time that my silly “western” cultural snobbery had no basis in fact.

“I usually don´t want him to carve such figures. I hate to sit here with it on the plaza and try to sell it. I get embarrassed.”

“You think he´d do one for me?” I pursued, still playing with her mind a little bit.

“Claro que sí.”

“Could he make him into a P´urepecha David?”

She grasped the enormity of my request at once.

“Sure, he´ll do whatever I tell him,” answered the little Indian woman, proud of the authority she had at her command.

Enedina and Eliseo Castillo and their family of 14 children are an industry. A very successful one at that. They are woodcarvers. All of them. And not just any woodcarvers, prizewinning ones.

I think it was the first time my friends David and Helen and I shared lunch with the Castillos in the shady dining room towards the rear of the family´s mostly outdoor compound: Eliseo sat at the head of the long table. Enedina supervised a cadre of young women, her beautiful daughters and daughters-in-law, as they set the table with white ceramic bowls, speckled blue peltre spoons, embroidered handmade cotton napkins. Soon they proceeded to load the table with steaming mountains of homemade corundas – the local triangular tamale – and great smoldering bowls of fragrant frijoles de olla, savory rice, verdolagas (lemony greens) spiked with chile manzano (the local chile that is similar to the blazing habanero), and piles of fresh tortillas de maíz as thick and tender as pancakes.

Eliseo told me proudly that none of his children had had to look for work “on the other side.”

“I wouldn´t let them go anyway. I´d miss them too much,” said Enedina from her customary station near the stove. Enedina never sat down to eat at the table no matter how vehemently Helen insisted. She said it was not her custom. She mainly hovered, interjecting her special wisdom into the conversation whenever it was needed.

Enedina´s father had taught her how to carve wood when she was just a child. Enedina taught her handsome young husband Eliseo. He taught all the kids. He started them out carving fish from soft pine sticks. Soon they graduated to avocado wood angels with great smiling faces and pretty little wings. All the angels look like Enedina, David noticed.

Thirteen-year-old César was up to the level of Risen Jesuses by the time we met him. I couldn´t resist buying his very first one. The face is beatific, eyes closed in peaceful, almost Buddhistic prayer. He hangs above my bed in silent repose. He is the first thing I see in the morning and the last before sleep at night. My Jesus sports cross-conquering arms jubilantly outstretched to welcome the whole sinful world to his kindly and generous bosom.

“Too generous,” Enedina informed her son. “El Señor would not have such a fat panza.”

“Right,” I said. “That tummy is more like mine.”

César grinned appreciatively at my silly joke, and Enedina frowned her playful frown. César likes his paunchy Jesus.

Three of the older Castillo sons — Julio, Eriberto, and Eliseo, Jr. — had recently been away from home for weeks at a time. Enedina was unhappy about their absence, but approved of the reason. They were carving all the saints and angels, as well as the Virgin Mary, and a crucified Jesus for a parish church down in the Tierra Caliente. Eliseo could barely contain his pride in his sons to have been chosen to do the job.

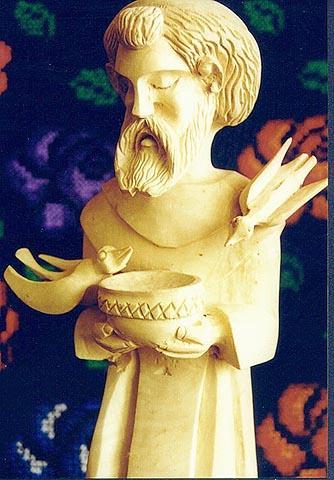

Eliseo is the master carver of the family, after La Maestra herself, and he occupies most of his time sculpting likenesses of the local Virgen de la Salud in cream-colored tropical hardwoods. That particular virgin is famous all over Michoacán for her miraculous healing powers.

There probably is no home in Pátzcuaro that doesn´t have an image of her somewhere within its walls. The ones Eliseo carves all have faces like his beautiful wife. Enedina denies that she is the model for all of Eliseo´s more sacred carvings, but that is just her modesty. I am certain I heard her mumble once under her breath, “What, and he should carve saints and virgins with the face of my neighbor, Señora López?”

The Castillo family are P´urepecha Indians, and they are proud of their heritage. They do not speak P´urepecha in their home, but their grandkids are learning the language, along with Spanish, in their elementary school. The family keeps up the old traditions, however. Their many weddings contain all the cheerful, ancient P´urepecha elements, such as carrying the groom around the party as if he were a cadaver. (“He is dead to his former, libertine life,” explained Enedina as we watched the videotape of the latest hitching of a Castillo son. “Or he´d better be!”)

Tocuaro, the village the Castillo´s have called home for generations, carries on the old ways as well, and Enedina and Eliseo are an integral part of the village´s celebrations. Eliseo carves and paints the contest-winning masks that are worn in various of the village´s fiestas. They are intricate and artful. They incorporate the ancient themes of serpents with twisting tails and demons with dangerously sharp tusks and fearsome black eyes. The masks are sanded silky smooth and painted with layer upon layer of bright paint, and flawlessly lacquered to a brilliant shine.

Enedina sews together the costumes that are worn with the masks–mostly by her own sons, who dance out the ancient tales for the edification and delight of the village children. These costumes are sparkling works of art in themselves. Her sequined costumes and Eliseo´s masks have been featured in magazines and photo art shows around the world.

The oldest sons also make fanciful animals that are called nahuales, although not characteristic of P´urepecha culture. These bizarrely imaginative creatures may have several heads, some with fangs and some with tusks, and maybe several lashing tails, and look more than anything else like creatures out of a nightmare. They are wildly painted and polished to a high sheen like Eliseo´s masks. They represent spirits, according to Eliseo and Enedina.

Tocuaro is traditionally a village of wood carvers, and there are many celebrated artists living within blocks of the Castillo´s compound. One difference that sets this family apart from their neighbors is that they still charge prices for their works of art that are within the range of most collectors´s. Another difference is that, for the most part, Eliseo and Enedina prefer to leave their works of art unpainted and unlacquered, except for the ceremonial masks and nahuales.

“I want them to see the quality of my carving,” Eliseo told me once as he sat in his lean-to at the back of the family compound. He always works in that place, sitting on a short stool, surrounded by fragrant mountains of wood shavings, and marvelous statues of saints and virgins and devils and angels rising up out of the shavings like phoenixes from the ashes.

All of his tools are handmade, some specially designed by him and made in forges in Mexico City or Morelia. They are beautiful and make me want to handle them, although as clumsy as I am, I know better. Eliseo´s rough hands caress them like they were old friends instead of razor sharp knives and gouges. His children work up on the shady roof of the house, but Eliseo likes to be close to the earth. He says it inspires his work. Almost as much as Enedina does.

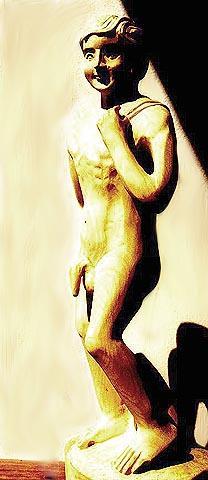

When our P´urepecha David is done, Enedina passes the word along through the Pátzcuaro grapevine. David and Helen and I pull up to the curb on the south side of Plaza Don Vasco in her beat-up old Dodge. Enedina and César are chatting with passing tourists from Mexico City and selling angels and fishes like they were loaves of Bimbo bread. César sees us and waves us over. He motions Helen to sit on a short wooden stool, a place of honor there under the portales where Enedina sets up shop, and David and I hulk around waiting for Enedina to finish her transaction.

“Where is he?” I ask excitedly.

“Oh, he´s in that market bag over there,” says Enedina. She sends César over to get our treasure.

“Well, show him to us, won´t you?”

César sheepishly pulls a newspaper-wrapped figure about a foot and a half tall out of the blue and white plastic bag. He slowly unwraps the head of the figure. It is beautiful, with large sad eyes and a slightly uneven mouth that smiles gently to the right.

“It´s the first time I have seen a carving by Eliseo that doesn´t have the face of Enedina,” I say. “But whose face is it? Looks so familiar.”

César blushes. I can tell he doesn´t want to expose the rest of the wooden beauty, and so I take it from his hands and continue unwrapping the newsprint. We see the thin, handsome chest. Next, the flat, white belly comes into view. And then, well, even I am reluctant to let the Mexico City tourists see what comes unwrapped next. I am speechless. David snickers.

Helen says, right out loud, “César! Díos mio! Are you the model?”