Of all the thousands of possible day-trips from tourist centers in Mexico, perhaps none is as varied, educational, beautiful and just plain fun as that along the eastern part of the Valley of Oaxaca. One of the great attractions of this trip is that it is less than fifty kilometers drive along a good highway to reach the furthest point. Numerous tours (out of Oaxaca) ply this route but few do justice to the extraordinary diversity that awaits you in the valley. An alternative, preferable if you really want to do justice when exploring this area, is to hire a car or car with driver and do it yourself!

Start early because there’s lots to see. In fact, it’s impossible to see everything here in a single day so either be prepared to come back, be selective as to which stops you make, or be ruthless as to how much time you allow yourself in each place.

The route follows highway 190 (which continues to the industrial port of Salina Cruz) and all the places mentioned lie very close to the highway.

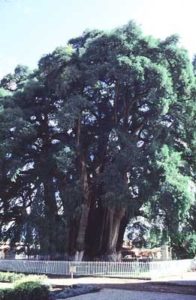

Just 15 minutes out of Oaxaca city is Santa María del Tule, a village which would probably have been consigned to a very minor role in history, and the guidebooks, were it not the home of the world’s largest tree. This monster tree, the largest-girthed in the world (35.8 meters or 117.6 feet at 5 feet above the ground) though not the tallest or most massive, according to the Guinness Book of Records, is simply humungous when approached from ground level. For that matter, it’s probably pretty big if you’re a bird! In the past, cynics could be heard claiming that this tree – a Moctezuma Cypress ( Taxodium mucronatum) – was really two trees with abutting trunks. But the definitive proof is now in. A study published in 1997 (quoted in Plant Talk) and based on random amplified polymorphic DNA testing (whatever that is!) confirms that the many hundreds of tons, metric or imperial, of this tule or ahuehuete definitely belong to the same, single, mammoth, 2000-year old tree. Protected by a wrought-iron railing and with its own irrigation system, this is one tree which definitely looks healthier now than it did ten years ago. If it were only easier to photograph, it might even be better known… To one side is its “little” child, big enough to be considered a giant in its own right anywhere else in the world except here.

After your brief stop in Tule, and your inevitable disappointment at failing to find a really good camera angle to remember the tree by, continue further east and take the turn (south) for the village of Tlacochahuaya. Here, an impressive former monastery, dedicated to St. Jerome, the patron of hermits, is delightfully decorated in brilliant colours. Worthy of admiration, too, are several old plateresque rococo altarpieces.

Back to the highway and only a few kilometers further east brings you to a roadside “pyramid” sign pointing the way to the small but important archaeological site of Dainzu. As you step out of your vehicle and look around, you’ll quickly realize that its name, derived from “hill of the organ cactus”, is certainly appropriate. Dainzu flourished as a smaller settlement, alongside Monte Alban until about 350 A.D.. Look for the striking jaguar-bat which decorates a tomb and for the depictions of the headgear, armgear and ball of the famous Mesoamerican “ball-players”. The ball game had mythological significance throughout central America although no-one has yet worked out precisely how it was played. Despite its significance, depictions of the ball game are frustratingly rare, hence the importance of Dainzu. The people hereabouts must have been very proud of some of the game’s players to have undertaken such a time-consuming task as laboriously chipping away at their rock walls to create such significant emblems.

Continuing east along the highway you soon reach the sideroad on the left (north) to Teotitlan del Valle, a town to which early Dominican missionaries introduced sheep – and wool. Teotitlan is famous today for woolen rugs, with designs ranging from animal motifs and Picassos to the geometrical, this latter style echoing the superb pre-Columbian stonework found at Mitla, the furthest point on this self-guided route. Indeed the skilled weavers of Teotitlan will happily craft by hand a customized one-off special design of any idea or picture you like, but be sure to allow plenty of time for them to complete it! Most modern-day production uses synthetic yarns and fibers and chemical dyes though traditional pure wool designs, using “natural” colours (which are generally less gaudy than their chemical equivalents) can still be found. The natural colours employed in Teotitlan come from recipes handed down through the generations and utilize such raw materials as pomegranate, pecan bark, prickly pear fruit, cochineal beetles and Pacific coast snails.

If buying wall-hangings or blankets here, expect to be engaged in a possibly lengthy bargaining session. If your Spanish is weak and you still want to drive a hard bargain, try writing the numerals constituting your offer on a scrap of paper. At least that way you avoid the ignominious difficulty, not to say embarrassment, afforded one of my friends who once bargained for almost an hour in the mid-day sun in his determination to beat the salesman’s ” quinientos” down to the ” cuarenta” he was prepared to pay. Only after lots of head-shaking and heated exchanges did it become clear that ” cuarenta” was not the same as ” cuatrocientos” and did not mean 400 as my friend had intended, but a positively miserly 40 pesos!

Furthermore, don’t expect to find that every example of weaving is 100% perfect. Indeed, perhaps you’ll never even find a single one that is exactly right. The oft-repeated tale of an artisan who never managed to produce a perfect piece in his chosen medium may well have had its origins in Oaxaca. According to the tale, a well-intentioned tourist spent hours and hours looking through the artisan’s stock and couldn’t understand why a minute examination of every piece revealed that every single piece, no matter how spectacular it looked at first sight, had some minor imperfection somewhere in the design or colour. When the artisan was asked how he could make such lovely items but still always fail to achieve perfection, he is alleged to have looked the tourist straight in the eye and said, “Why, señor, only our Lord is allowed to do that!” Perhaps so, but believe me, touring the studio-workshops of the local small villages and towns, each noted for their own distinctive wares and crafts, makes for a formidable shopping experience, even if you don’t buy a single “perfect” item!

In keeping with the archaeological underpinning of this entire valley, Teotitlan del Valle was settled during very early Zapotec times, even before Monte Alban. There is little to see now but the site was originally dedicated to Xaguije, a celestial constellation that descended to earth in the form of a brightly-coloured macaw or guacamaya.

Back on highway 190, watch out for a pyramid sign on the right, marking the entrance to Lambityeco. This small but fascinating site lies very close to the international highway and yet is surprisingly little visited. It features some of the most intriguing stonework in the entire valley. Molded stucco friezes over Tomb 6, suggest its former occupants were Lord 1 Earthquake and Lady 10J. Murals and stucco rain-god masks are the highlights to seek out at Lambityeco. In olden times, salt was produced here by evaporating or boiling water drawn from the subsurface reserves and some authorities believe that the name Lambityeco combines the elements of the Spanish term alambique (still) and the Zapotec word pityec (mounds).

A short distance beyond Lambityeco, also to the right of the highway, is the town of Tlacolula, the site of an enormous street market, held each Sunday. On the opposite side of the highway from Tlacolula is a very well-signed mescal factory but, for several reasons, it is preferable to save visiting this until you return this way a little later in the afternoon…

Tlacolula, whose generally scruffy character belies the origin of its name (said to derive from an expression meaning “town of heaven”), had a reputation for decades as a great place to buy good quality leather sandals or huaraches, the original backpacking kind, made out of discarded Goodyear tires, with a depth of tread guaranteed to outlast a lifetime of regular use. Today, most visitors to the town are less interested in trying on huaraches than they are in seeing the church of Our Lord of Tlacolula.

Once a Dominican mission, the best-known part of this seventeenth century church is the polychromatic chapel on its south side known as the La Capilla de Plata (literally the Silver Chapel), aptly described by Richard Perry, the authority on colonial ecclesiastical architecture, as a “gem of folk baroque style” and a “triumph of popular art”. Among the stucco statues in its interior, seek out John the Baptist, portrayed holding his severed head out in front of him. The church has several examples of fine wrought-iron work, including the railings around the pulpit and, according to one guidebook, also houses an antique tubular pipe organ though I must admit I forgot to check this particular detail last time I was there.

From Tlacolula, it is only a short drive to the lovely setting of Yagul, where the remains of another Oaxaca Valley pre-Hispanic settlement nestle up against the steep valley side. For some difficult-to-pinpoint reason, Yagul (= old tree) is many people’s favorite Oaxaca area site, preferred even to the majestic setting of Monte Alban and the unique site of Mitla. Yagul is not only much less visited but far more intimate, more serene and somehow more compelling. Listen to the neighborhood birdlife as you stroll between the mounds and walls fashioned out of rounded volcanic pebbles that owe their shape to being bounced, pushed and cajoled along the bed of the nearest river. A larger-than-lifesize frog effigy stands close to a perfectly proportioned ball court. All the evidence points to Yagul having been an independently successful city state, roughly contemporaneous with Mitla. Climbing the hill that forms the backdrop to Yagul’s main constructions affords an outstanding view across the valley. Here, high on the hillside, lie several tombs and lots of potsherds and obsidian slivers.

Between the parking lot for Yagul and the highway is the strangely-named Centéotl restaurant-bar-gallery (Tel: 956-20289), which offers traditional regional cuisine under the shade of a large palapa. The restaurant’s name is somewhat incongruous in this warm, semi-arid homeland of the Zapotec and Mixtec Indians, since Centéotl is the Aztec god of agriculture, who more rightly belongs in central Mexico, far to the west.

The furthest point on our day-trip, Mitla, inspires a strange and wonderful mixture of feelings. Only 48 kilometers from Oaxaca, Mitla (usually, though not with certainty, interpreted as “place of the dead”) was one of several city states in the Oaxaca valley and was in full flow when the Spanish arrived in the sixteenth century. The Spaniards thought they knew just how to ensure that their God would be seen to have more importance than the Indians’ gods – they built His church so that it would tower over Their temples, and used stones pulled from the pre-Hispanic walls to make their construction task that much easier. The massive seventeenth century church of San Pablo Mitla still broods over the remains of “heathen” palaces; its foundations sit atop a platform dating from centuries before the Conquest.

If Mitla really does mean “place of the dead”, then surely the dead must have been Kings, since the lavish stonework throughout the site is unequalled anywhere else in Mexico. From the beautifully sculptured designs in the Hall of Mosaics to the Hall of the Columns, virtually every wall is decorated in an intricate geometric step design. This “fret-stone” work, for want of a better description, has withstood the dozens of earthquakes that have occurred since it was first used in around 200 A.D. in this crustally-active region. The correct architectural term for the geometric patterns of small mosaic pieces of volcanic rock, which are like an outer skin on a mud and rubble interior, is ” grecas”, often and regrettably misinterpreted or mistranslated as “Grecian”, giving rise to some inevitable cultural and historical misunderstanding. The complicated greca patterns can be followed by eye or hand and resolve themselves into representations of the Sky Serpent, one of the many guises of the Feathered Serpent, Quetzalcoatl.

In the depths of one of the palaces is La Columna de la Muerte (the Column of Death). The legend is that you wrap your arms around this pillar and see how much distance remains between your outstretched fingertips – the distance left is said to represent the time you have left on this earth. True or not, crowds of Indians used to gather here every New Year’s Day to try out their arm-size and, presumably, their luck.

At the entrance to the ruins is a small museum of archaeological artifacts. Alongside is a bustling handicraft market, a perfect place to find small inexpensive souvenirs or gifts for family or friends back home.

In the main part of the town, across from the small plaza, is the building which was formerly the Posada La Sorpresa, a small inn that played host to such famous authors as D.H. Lawrence (“Mornings in Mexico”) and Malcolm Lowry (“Under the Volcano”).This building later housed a small museum. Sadly, this museum is now closed; the location of the pieces from the museum is unknown.

If you are in no hurry to return to Oaxaca or still have plenty of time on your hands, then consider continuing on through Mitla towards San Lorenzo Albarradas. Near San Lorenzo (only limited accommodation available) is the extraordinary landscape of Hierve El Agua, the remains of an irrigation system built and used by the Zapotecs from as long ago as 700 B.C.

On your way back to Oaxaca city from Mitla, try to allow time for at least one more stop, even if only a brief one, to savor the mescal made in one of several “factories” on or close to the International Highway. For example, at kilometer 32, near Tlacolula is Pensamiento Mezcal.

Mezcal, or more usually (in English) mescal, is an alcoholic drink derived from various types of agave, as opposed to tequila which is, strictly speaking, made only from the blue agave.

At Pensamiento Mezcal, as at most other mescal producers, someone will be delighted to explain the basic processes involved in making mescal. The drink comes in various grades, including 100%-agave reposada or aged. The traditional version includes a gusano de maguey or agave worm (long deceased and well sterilized by the alcohol) floating around in the bottle. Flavored mescals (without the worm) are also produced; a non-exhaustive list of flavors includes mint, orange, blackberry, grape, strawberry, lime, guava, coconut, coffee and peach. The roadside Pensamiento plant also showcases interesting antique items which help you understand how mescal used to be made in the good old days. After looking around, you’ll likely be offered a “tasting”. While a true taste for mescal undoubtedly has to be “acquired”, don’t pass up the chance to try this increasingly fashionable (“muy de moda”) and increasingly expensive drink.

A late afternoon toast in mescal may seem to many visitors like a fair and just reward for a long day’s sightseeing, but please ensure that those doing the mescal sampling are not those responsible for driving you back to the city…