Did You Know…?

Besides being used as a kind of rough paper for records and correspondence, amate was also cut into human or animal forms as part of witchcraft rituals after which it would be buried in front of the person’s house or animal enclosure. Colorful paintings on papel amate or bark paper are sold throughout central Mexico, virtually anywhere there are tourists. The tradition is an ancient one. The word amate derives from amatl, the Nahuatl word for paper. Several Indian groups in Mexico perfected the art of making bark paper and used it for centuries in their rituals.

About fifty years ago, cheaper, mass-produced alternatives threatened to wipe out the small-scale artisanal production of bark paper. Fortunately, the practice survived in several places, and the ancient art was revived and rejuvenated.

Originally, the color of the paper was entirely dependent on the type of bark used, but in recent years, the addition of dies during processing has resulted in a kaleidoscope of colors, ideal for many kinds of artistic projects. The classical mid-brown bark paper is produced from the bark of several members of the amate or wild fig ( Ficus) family. Off-white, or silvery-beige bark paper requires mulberry ( Mora) trees.

True amate paper is still hand-made. One of the centers of production is the Otomí village of San Pablito in the state of Puebla. Villagers wash the bark, boil it with a solution of lime juice for several hours, and then lay it in strips on a wooden board. They then beat these pulpy strips with stones called muintos or aplanadores until they fuse together to form the desired texture of paper, which is then allowed to dry in the sun.

Centuries of practice enable them to produce amate paper of any thickness, from the equivalent of crepe-paper to poster-board. Visitors to San Pablito quickly discover that the constant sound of pounding is a distinctive reminder of the village’s main industry.

Amate trees are common in central and western Mexico, and some species are quite distinctive. For instance, Ficus petiolaris, which has heart-shaped leaves and whitish-colored bark, is often found growing with its roots extending down rocky slopes, canyons and roadsides. Mature trees can be up to 25 meters in height, but with fruit too small and dry to be of interest to humans. The fruit may be useless, but botanists have discovered that the pollination systems of these wild figs are quite bizarre.

The following description is based on that in Costa Rican Natural History (Edited by Dan Janzen, University of Chicago Press, 1983).

In brief, each species of fig depends on its own species of pollinating fig wasp. When the tree is covered with tiny green figs, thousands of these wasps appear, presumably attracted by a scent released by the tree or the figs. Female wasps, pollen pockets already filled, enter the young fig by wiggling through a tiny hole in its apex. As they do so, they lose their antennae and wings. Once inside, the female wasps pollinate the stigmata in each fig. Some females will also succeed in laying eggs inside the fig. About a month later, by which time the seeds are full-size, the next generation of male wingless wasps is born. First, they find a female wasp to copulate with. Then they chop an exit hole in the fig, allowing the female wasp, her pockets filled with pollen, to escape and fly off in search of yet another fig now ready for pollination… and so on. This is an interesting example of two species whose lives are so intricately entwined that apparently one can no longer exist without the other.

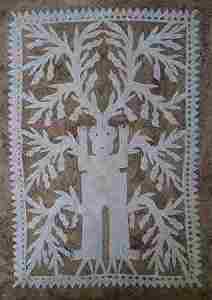

The illustrations accompanying this article show details from amate paintings in the author’s private collection. Most amate art depicts stylized scenes of everyday life. Bright colors, and vivid contrasts are used to great effect to portray people, animals and flowers, as well as landscape elements such as rivers. Higher quality amate paintings, which can fetch very good prices, are generally signed by the artist.

Further Reading

- Amate Art of Mexico (Where the Secular Meets the Sacred) by Rita Pomade