Juan Mata Ortíz is a small village of potters, farmers and cowboys in Northern Chihuahua. About 30 years ago, an unschooled artistic genius, Juan Quezada, taught himself how to make ollas, earthenware jars, by a method used hundreds of years ago by the prehistoric inhabitants. Now, his works are known worldwide and over 300 men, women and children in the village of less than 2000 make decorative wares. Much of the polychrome and blackware is feather light and exquisitely painted.

Many of the potters are also cowboys and farmers. These stories serve to document the art and the people in this unassuming pueblo, an art that is often called “magical” by the relative handful of tourists who visit. Enjoy this other view of Mexico.

Mata Ortíz lost a good friend the day before Thanksgiving, 1998. John Davis died of natural causes in his trailer home in Deming, NM.

I had seen and heard of John Davis for almost a year before I finally met him in Mata Ortíz nine years ago. Even before I knew him, I was aware of the word that best described him: giving. John was always giving: candies, polishing stones, knowledge, sundry items and, especially, – friendship.

Our paths didn’t cross for some time because I was usually afoot, wandering the dusty, potholed streets on my way to visit one potter or another. Several times, while walking with my friend and artist, Nícolas Quezada, he pointed to a small white station wagon across the arroyo or flitting around a corner.

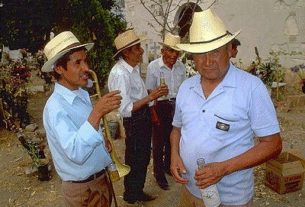

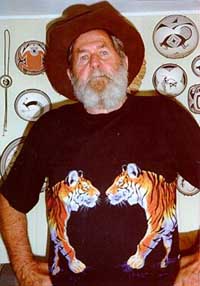

” Allá está El Gringo de los Dulces, There is the Gringo of Sweets,” he’d say. John always seemed to have a bag of candies with him and children would flock to his vehicle when he’d stop to visit a potter and buy some pots. He was short & stocky. A bushy white beard embraced a face often emblazoned with smiles-except when he spoke Spanish. Then he was usually serious, eyes narrowing in concentration.

A memorial service was held for him in early December in El Paso. The time was near sunset, the location a ramada with a spectacular view of the desert and raw mountains. Those same low crags slipped from purple to red to orange as the sun dipped towards the horizon. Fifty or sixty people and myself listened to his brothers, sister and close friends reminisce about this special man.

A memorial service was held for him in early December in El Paso. The time was near sunset, the location a ramada with a spectacular view of the desert and raw mountains. Those same low crags slipped from purple to red to orange as the sun dipped towards the horizon. Fifty or sixty people and myself listened to his brothers, sister and close friends reminisce about this special man.

John’s life could have been made into an adventure novel. There was a litany of his close calls with death. As a young man in Wyoming, John survived a close encounter with a tractor when the steel wheels rolled over his chest. During World War II he qualified for the Purple Heart but never applied for it. There were enough close calls in Southern Mexico and Guatemala to make a four-part mini-series on TV. Even in sleepy Deming an errant bullet once snicked into his trailer wall as he sat on the patio watching the ever-present birds. He also wrestled steers and broke horses in his earlier days. Somehow, he found time to earn an electrical engineering degree and become fascinated with Southwestern rock art – of which there is an abundance in the Hueco Tanks State Park near El Paso.

John had been a collector since he was a kid, according to his brother. They found over 300 pounds of coins from around the world in his trailer. It’s not surprising that he found Mata Ortíz. John first visited Mata over 20 years ago. There were few potters, many homes still did not have running water (some didn’t even have electricity) and there were only a handful of outhouses in the village. He became infatuated with the potters and their pottery and began buying – not to sell, but to collect.

He had a philosophy about collecting. His interest was not with the masters, but the up and coming potters who would one day be masters. He never negotiated on a price. If he felt the ceramic was too expensive, he just didn’t buy it. He knew someone else would. I often saw him pass up pieces brought to my home in the village. We’d be sitting in front of the fireplace with our margaritas or rum and Cokes and potters would shyly come in to show their wares. If John didn’t take it, someone else at the same table would jump at it. When John first started visiting Mata Ortíz, many potters didn’t polish their earthenware either before or after firing. Those that did used pieces of plastic or bone. Often the results weren’t great.

The Gringo of the Dulces could also have been known as the Gringo of the Piedritas, little rocks. Each spring, John would haul in about 200 pounds of small stones rendered silky smooth in lapidary shops and collected at a huge rock and gem show held annually in the southwestern Arizona desert. These bags of stones, rattling kaleidoscopes of color, were taken from house to house. John allowed three stones per potter. The selection process could take a half hour or more, as the artists and craftspeople in each home pawed through the pile, looking for just the right shape for polishing and the proper configuration for their hands.

Naturally, these were gifts. John received nothing in return, except gratitude and friendship.

The polishing stones were one of the most significant contributions to the growing cottage industry in the village. Now, most potters polish their earthenware before painting. After the paint dries, they re-polish the designs, “set the paint,” as they put it. The result is a ceramic as smooth and clean as fine china.

There won’t be bags of polishing stones brought into the village this year, but John Davis’ gift will continue to live on as those stones, in the hands of these incredible artists, help produce some of the most exquisite pottery on this planet.